Cancer treatment is typically brutal and terrifying. The very nature of the “therapy” is at odds with the concepts of survival or healing. In order to get “well,” a cancer patient must agree to subject her body to a host of things she instinctively fears — radiation, toxic chemicals, mutilating surgery. The experience is not only horrifying but incredibly isolating. Caregivers hide behind lead-shielded partitions or don gowns and gloves as they administer the poisons that are meant to “cure.”

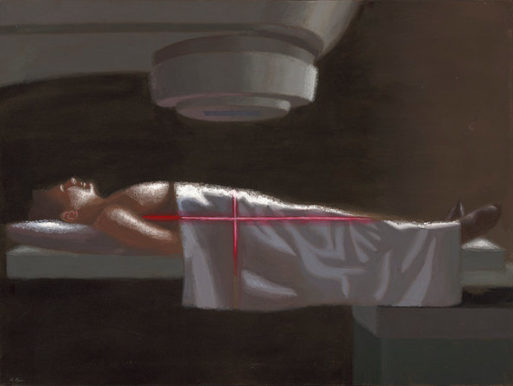

“Radiation,” by Robert Pope (1989)

Credit: Robert Pope Foundation

Several years before he died from Hodgkin lymphoma in 1992, Canadian artist Robert Pope chronicled the dystopian landscape of the cancer unit in a series of paintings, now part of the book “Illness and Healing: Images of Cancer” originally published in 2002. Starkly realistic yet simultaneously surreal, they invite us to view the cancer ward through the patient’s eyes.

Many of the paintings are difficult to look at. Though not at all graphic, they convey the helplessness that comes with a cancer diagnosis — the need to quell the desire to run away in terror and allow the unthinkable to become real.

Take “Radiation,” for example, which shows a man lying on a platform staring up at a monstrous X-ray machine. There are red lines bisecting his body in the shape of a cross. He lies stiffly, staring blankly up at the machine, looking more like a victim in a horror movie than a patient hoping for a cure. As Pope wrote, “…the machine hovers above him like an idol or faceless god that must be propitiated with bodily sacrifices,” expertly conveying what it’s like to act against all reason and accept the lethal beam of the X-ray machine.

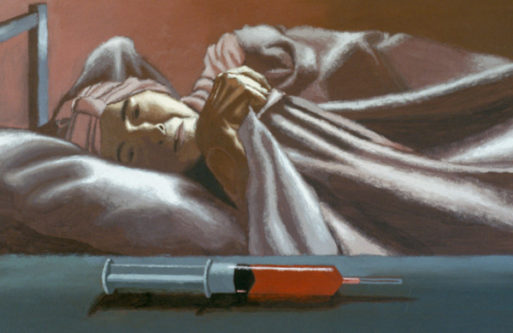

“Chemotherapy” by Robert Pope (1989)

Credit: Robert Pope Foundation

Another painting, “Chemotherapy” shows a woman lying in a hospital bed staring at a large syringe of Adriamycin — one of a group of chemotherapeutic agents called anthracyclines, which are typically colored a bright, toxic-looking red. Her head is wrapped in a scarf — the badge of honor of women with cancer everywhere — and she clutches the bedcovers tightly as she stares at the syringe. In her face we see anxiety, resignation, and the helplessness of knowing she can either accept this fate or die. It is a powerful image, and one that, according to the Robert Pope Archive, affected many doctors so deeply that they changed their practice, no longer leaving chemotherapy at a patient’s bedside in such a callous and cavalier way.

“Hug” by Robert Pope (1990)

Credit: Robert Pope Foundation

Still other paintings in the collection speak to the devotion of friends and family, which are arguably the most essential touchstone in a cancer patient’s life. In “Visitors” for example, we see a patient, visible only from the chest down, lying in bed surrounded by loved ones, each imbued with a distinct emotion, but all appearing somewhat shell-shocked and afraid. And in “Hug” a man holds his ailing wife close in an intimate gesture of love and support, both of them seemingly oblivious to the IV tubing hanging from her arm.

The paintings in Robert Pope’s “Illness and Healing” collection are a powerful body of work, all the more so because they depict a reality that has changed hardly at all in nearly 30 years. Since then, we have explored the surface of Mars, invented the internet, and put tiny personal computers into the pockets of close to 2.5 billion people across the globe. We have designed unmanned drones to wage our wars, and soon we will have supersonic passenger jets that will take us from New York to London in 3 hours flat.

Yet we are still treating cancer in much the same way as we did three decades ago. Somehow that seems like we’ve got our priorities wrong — again.

To learn more about Robert Pope, his work and his legacy, visit the Robert Pope Foundation and the Robert Pope Archive.

“Illness and Healing: Images of Cancer” by Robert Pope

“Illness and Healing: Images of Cancer” by Robert Pope

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”