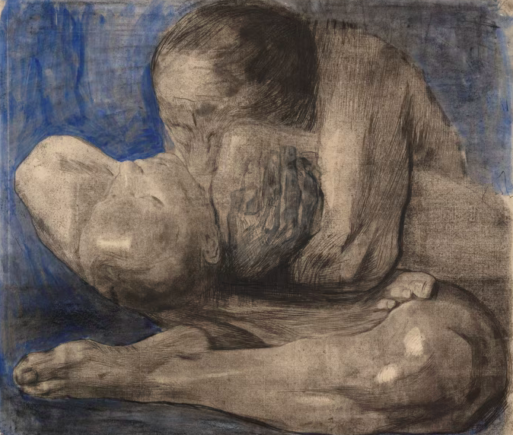

“Woman with Dead Child” (1903) by Käthe Kollwitz

Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

German artist Käthe Kollwitz was not one to turn away from the darker parts of life. Her work was informed not only by the suffering witnessed all around her, but also by her personal encounters with death and grief. Now, the MoMA is showcasing the largest exhibition of her work in more than three decades, and the first major retrospective at a New York museum.

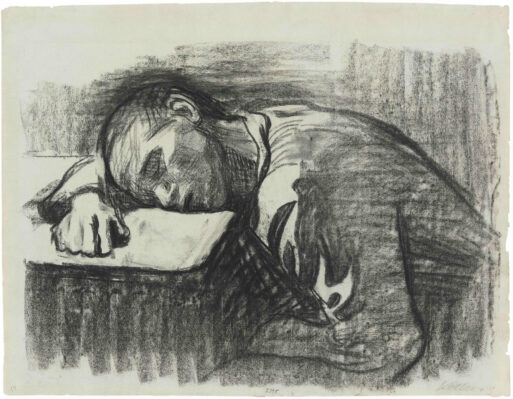

Kollwitz, who explored painting before finding her home in drawing and printmaking, was a fierce advocate for working class people in Berlin, where she lived for most of her life. “It is my duty to voice the sufferings of men, the never-ending sufferings heaped mountain high,” she wrote in her diary, according to MoMA.

“Home Worker, Asleep at the Table” (1909) depicts hardships of working-class women.

Credit: www.moma.org

One series – “A Weaver’s Revolt,” which was inspired by an 1844 uprising – was nominated for a gold medal at the 1898 Great Berlin Art Exhibition. But the prize was revoked due to controversy, or perhaps due to the fact that Kollwitz was a woman.

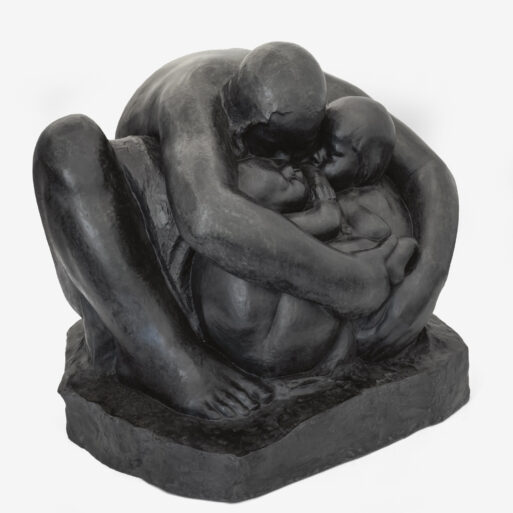

“Mother with Two Children” (1932-36) memorializes maternal love.

Credit: www.moma.org

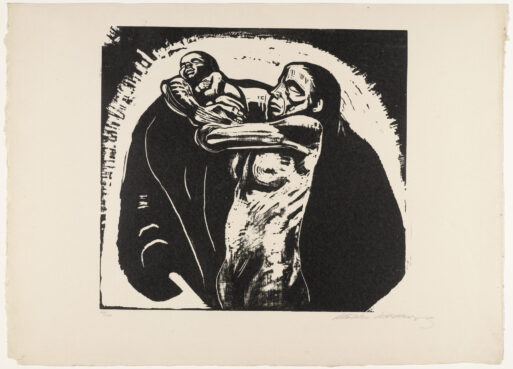

The versatile artist also drew on her own experiences with loss, including a son who was killed in World War I. Later, her grandson was killed in action in World War II. Kollwitz’s depictions of war often focused on mothers in the throes of grief.

“The Sacrifice,” a 1922 woodcut, depicts women’s loss admidst the violence of war.

Credit: www.moma.org

Kollwitz literally faced the world head-on, and was one of the first women to do so with her 1904 lithograph, “Self-Portrait en face” — an assertive, fully frontal portrait that disregarded classic approaches to femininity. She was also the first woman elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1919, where she remained until the Nazis mandated her expulsion. And her 1934-37 series of lithographs, titled “Death,” was disturbingly prescient in its depiction of people – mostly women and children – encountering death at various stages.

The Käthe Kollwitz retrospective at New York’s MoMA, where it is now on display.

Credit: www.moma.org

Kollwitz died in 1945, just weeks before the war’s end in Europe, and two years after bombings had destroyed her studio and much of her work. She is often considered the last great German expressionist.

MoMA’s Käthe Kollwitz retrospective, which features around 120 drawings, prints and sculptures from public and private collections in North America and Europe, is on display through July 20, 2024.

Käthe Kollwitz Evokes a Mother’s Grief at New York’s MoMA

Käthe Kollwitz Evokes a Mother’s Grief at New York’s MoMA

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”