The Taj Mahal

(credit: travelwebdir.com)

Emperor Shah Jahan loved the Persian princess, Mumtaz Mahal, with such a passion that after her death, he expressed his grief by constructing a memorial so magnificent — it became one of the Seven Wonders of the World. The Taj Mahal, in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India, is considered by many to be the most beautiful building on Earth. Blending the styles of Islamic, Persian, Ottoman Turkish and Indian architecture, this monument is not just a stunning palace that has drawn millions of admiring visitors throughout the ages, but a monument to eternal love. In the words of Sir Edwin Arnold, the twentieth century British poet and journalist, the Taj Mahal is “not a piece of architecture, as other buildings are, but the proud passion of an emperor’s love wrought in living stones.”

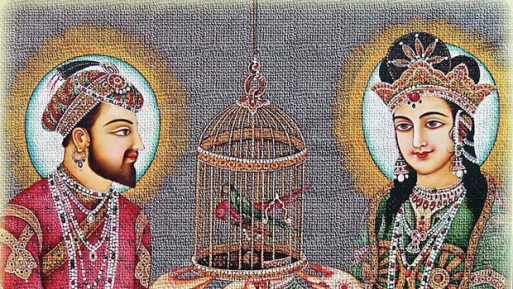

Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal

(credit: newindianexpress.com)

Even though it’s a story of loss, the tale of Taj Mahal has stuff that fairy tales are made of and it begins in an exotic, bustling market. The Royal Meena Bazaar was a private marketplace where highborn ladies went to shop for exclusive oils, dyes and fabrics and where no man dared to enter for the fear of losing a limb from such an indiscretion. Yet there was a day or two every month, when the Royal Meena Bazaar was open to everyone and the refined and privileged young women of the court amused themselves by playing the roles of the noisy, flirtatious shopkeepers.

On such a day, in 1607, a young Indian prince, Shah Jahan, strolled through the market. At sixteen, he was already a skilled gifted poet, a talented singer and an experienced architect, but that day, a girl selling silk and beads at the Royal Meena Bazaar eclipsed all his other pursuits. Fifteen-year-old Arjumand Banu Bagum was the daughter of a protective father, the Persian prime minister, who demanded respect. Only a prince would dare to flirt with the prime minister’s daughter who was a highborn beauty. Young Shah Jahan tried speaking to Arjumand in a refined Persian verse, but ended up speechless and in love. He immediately informed his father, the emperor, of his intent to marry Arjumand. Five years later, the princess and the prince celebrated their marriage and sixteen years after that Shah Jahan himself became an emperor and Arjumand held the title of Mumtaz Mahal — “Jewel of the Palace.”

Not a piece of architecture, as other buildings are, but the proud passion of an emperor’s love wrought in living stones. — Sir Edwin Arnold

Before Mumtaz Mahal, the emperor already had two wives, but Mumtaz became his absolute favorite. They were inseparable, and Shah Jahan even entrusted Mumtaz with the royal seal. According to accounts and customs of that time, Mumtaz Mahal was the perfect wife: gracious and compassionate, supportive and knowledgeable in her husband’s affairs and without any wish for power. She accompanied the emperor everywhere, even into battle. In 1631, Mumtaz died while giving birth to their fourteenth child. During his farewell, Shah Jahan promised Mumtaz he would build a magnificent palace in her memory and never take another wife.

Taj Mahal Mausoleum

(credit: travelwebdir.com)

So bereaved was Shah Jahan, he forced the court into two years of mourning and started on his promise of building an edifice in honor of his wife. Twenty-two years later, built by the hands of 22,000 builders, a marvel made of shimmering white marble and semi-precious stones rose up by Yamuna River. Its central dome reached ten stories high and housed the mausoleum containing the false tomb of Mumtaz, while her real sarcophagus lay buried among the pools and gardens below.

A legend tells that after the completion of Taj Mahal, Shah Jahan had cut off the hands of all the builders and artisans who worked on it. It’s unlikely, since Jahan also had a plan to build a monument to his posthumous self across the river and have it joined with Taj Mahal by a bridge. That never happened. Shah Jahan, unseated by his own son in 1658, spent the end of his life confined under house arrest, but with a view of the monument to his beloved wife across the river, until he too was buried in Taj Mahal.

Love Wrought in Living Stones

Love Wrought in Living Stones

Having an Estate Plan Is Essential – So Is Discussing It With Your Children

Having an Estate Plan Is Essential – So Is Discussing It With Your Children

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales