Joe Mullins, a forensic artist with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, cannot give the gift of life back to eight unknown migrants whose dehydrated remains were found in the Arizona desert near the U.S.-Mexico border a few years back. But, by combining fine arts and forensic science, he is working on reclaiming their identities, starting with a workshop held last March at the New York Academy of Art.

Credit: YouTube

Earlier this year, Mullins moved the investigation of the dehydrated bodies from the Pima County medical examiner’s office in Tucson to a class in facial reconstruction at the Art Academy. The unique combination of diverse disciplines is now helping to identify the unknown eight male migrants found near the border.

The workshop taught by Mullins focused on reconstructing the faces of the migrants who lost their lives in the desert. It employed recent advances in the field of forensic facial reconstruction, in which the skull is used to build a face that can help investigators identify the dead person The procedure has been used before in cases of crime and mass disasters.

Credit: YouTube

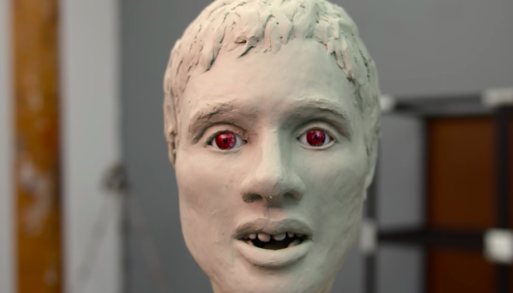

Since it is against the law to use real skulls, graduate students (whose training included anatomy) worked with 3-D-printed replicas of the men’s skulls based on CT-scans of the originals found in the desert. They carefully sculpted clay onto the skull facsimiles and used marbles for eyes with a black Sharpie dot marking the pupils. The reconstructed faces were on display at the Academy by the end of March.

Mullins explained to the New York York Times that, to a trained eye, the structure of the human skull offers a blueprint to the facial features. “A skull is the foundation an individual’s face is built on,” said Mullins, 47. Based on that foundation, the graduate students analyzed clues that might indicate the thickness of the lips, the shape and placement of the eyes, nose and chin, the earlobes, even the curve of the eyebrows that were part of the face once associated with the skull. Mullins cautioned his students against taking artistic license in reconstructing the face. They had to let the bone structure dictate the features. “If you put the wrong face on, that person is going to stay lost,” said Mullins.

In a 2015 YouTube video, Mullins conducts a similar workshop at the New York Academy of Art where students work on the skull replicas of 11 New York City homicide victims in an attempt to restore their identities. It had taken eight years for the ground-breaking class to come about. In the video, Mullins talks about the extent of the reconstruction process saying, “I stop when I see a face staring back at me.”

“We’re visual creatures,” said Bruce Anderson, a forensic anthropologist with the Pima County medical examiner’s office. “When we don’t have a viewable face, because of decomposition, we ask artists to give us the impression of what the person looked like in order to draw attention to a particular case.” The migrants’ facial reconstructions have been posted on NamUs, the National Institute of Justice’s National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. The hope is that someone who knew the unidentified person will see something in the reconstruction that sparks recognition and notify the authorities of a potential match.

Migrant deaths along the United States border with Mexico rose last year despite a steep decrease in attempted crossings, according to the United Nations Migration Agency. Since 2001, the remains of roughly 2,800 migrants have been found in Pima County alone. Of these, roughly 1,000 people are still unidentified.

New York Academy of Art Students Help Identify Migrants Who Died at the Border

New York Academy of Art Students Help Identify Migrants Who Died at the Border

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull