Alkaline hyrdrolysis turns human remains into nutrient rich liquid

Credit: Sam Coulton via dezeen.com

Sam Coulton is a London architectural student who has been looking for a solution to a problem: London is rapidly running out of burial space. According to a 2015 BBC report, nearly half of London’s cemeteries will run out of space within the next 15 years. And while cremation is a viable and very popular alternative (according to the Cremation Society of Great Britain, 75 percent of UK residents chose cremation last year), it is not without its drawbacks, especially with upwards of 200 Londoners being cremated every day.

So Coulton, who is working on a masters degree at the Bartlett School of Architecture, came up with an idea. He devised a plan for a more sustainable alternative to cremation and burial that will also help his fellow Londoners confront the social, economic and environmental implications of death.

A Novel Idea

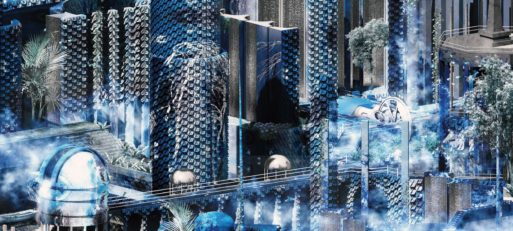

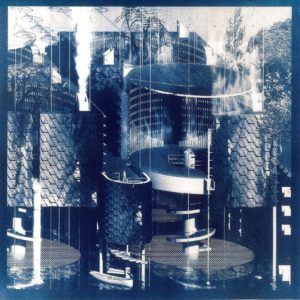

Sam Coulton’s project is called the London Physic Gardens: A New London Necropolis, a so-called “city of the dead” located on the former site of the Chelsea pleasure gardens. The site will use the liquid end-product of alkaline hydrolysis — a process that uses water, lye and heat to dissolve human remains — to grow a variety of plants for the RHS Chelsea Flower Show. In a twist that Coulton hopes will “shock the living Londoner into engaging environmentally and socially,” the corpses would first be wrapped in shrouds infused with the environmentally neutral and non-toxic pigment, Prussian blue. This would turn the water in the alkaline hydrolysis chamber and the resulting effluent blue. Over time, Coulton imagines, the pigment would leech into the soil and gradually turn London’s waterways — including the iconic Thames — blue. It would also enter the water cycle, and as the blue pigment rained down on the city, London’s architecture and even its smog would turn blue as well.

Artists rendering of the London Physic Gardens Credit: dezeen.com

Coulton was inspired by the work of filmmaker, gardener and gay rights activist Derek Jarman, who directed the film “Blue” as he was going blind from AIDS, and Yves Klein, who described his blue monochromes as “something eternal, transcending human life and time itself.”

His project focuses on the problems of “extreme climate uncertainty, population growth and political instability due to impulsive decision making with little regard for the past or future Londoner,” Coulton explains. He believes that the gradual transformation of the city would help Londoners begin to “see death and body disposal as something civic and potentially beautiful,” and force “the city of the living to engage with the city of the dead, in the present, for the benefit of the future, and of the past.” Further, he adds, the rejuvenated gardens would serve as both a horticultural display, a source of medicinal plants, and a place of mourning where loved ones could come to remember those they had lost.

Sam Coulton’s rendering of a the city of London turning blue

Credit: samcoulton.wixsite.com

Coulton also hopes his project will help Londoners better understand the environmental benefits of alkaline hydrolysis and accept it as a viable alternative to either burial or cremation. “In 1960, about 30 percent of deceased Britons were cremated,” he says. “Now it is over 70 per cent. Attitudes continue to change, and if flames are better than worms, why is water not preferable to either?” he adds.

Sam Coulton Designs a New Necropolis

Sam Coulton Designs a New Necropolis

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition