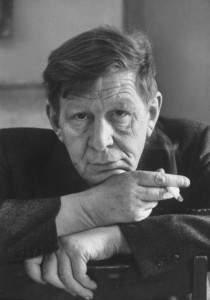

Though it came out in 1994, I watched Four Weddings and a Funeral for the first time last year. The movie is known for its two Academy Award nominations (Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay), and for launching Hugh Grant’s career; but what stuck with me the most (and perhaps with you, too) was the scene in which W.H. Auden’s “Funeral Blues” is recited during the film’s titular funeral. In fact, the movie renewed interest in Auden’s work after featuring his poem. Though it has come to be a bit cliché as funeral poems go these days, I still find “Funeral Blues” moving.

I debated as to whether I should use the poem for this column, since its tone is so dismal, but I think it’s a realistic depiction of grief, and a perspective that can’t be ignored. After the loss of someone very close to him, the poem’s narrator feels that nothing can ever be the same again. He feels that the world around him should reflect his inner feelings of shock and turmoil; the poem’s notorious first line is proof of this: “Stop all the clocks…” (1). The narrator asks that other such occurrences be ceased. He requests that the telephone be “cut off” (1), and that the dog be “prevent[ed]…from barking with a juicy bone” (2). These are all normal, everyday happenings, but the narrator is bothered by them, as he can’t understand how the world can go on in the same way after this death.

The last few lines of the first stanza and the whole of the second are even more melancholy, with statements like, “Silence the pianos and with muffled drum/Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come” (3-4), and “Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead/Scribbling on the sky the message ‘He is Dead’” (5-6). The narrator wants the whole world to be aware of this death because he himself is so affected by it. It is all that he can focus on, so he wants others to be able to empathize with him. This is solidified by the line, “Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves” (8). Even the policemen of the area must be aware of this death and be in mourning.

In the third stanza, the narrator expresses how the man he lost was everything to him: “He was my North, my South, my East and West/My working week and my Sunday rest…” (9-10). By including all directions and all days of the week, the narrator shows that this man was his life; he was involved in everything the narrator did. In this same vein, the narrator continues, “My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;/I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong” (11-12). This last sentiment, of love not lasting forever, is one that I have tended to counter in my previous posts; but I think that when the wound of grief is so fresh, this is a common feeling among mourners, and one that should not be discounted.

The fourth and final stanza is my favorite, because of its figurative language:

The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good. (13-16)

I love that such impossible tasks are laid down as if they are simple chores: the moon can be “pack[ed] up” (14) and the ocean “pour[ed] away” (15). These lines convey the hopelessness the narrator feels. He doesn’t think that any of these aspects of nature should exist any longer, since his world has been turned upside down by his loss. He is so forlorn that he doesn’t believe anything now “can ever come to any good” (16). It may be a dejected view, but it beautifully illustrates the pain that comes with a loss. It’s hard to lose the people that mean the most to us, and Auden’s poem makes no attempt to deny this.

Conveying Grief Realistically

Conveying Grief Realistically

“Comeback” by Prince

“Comeback” by Prince

“Other Side” Documents Woman’s Fight To Die As She Wishes

“Other Side” Documents Woman’s Fight To Die As She Wishes

The Other Death in the Family

The Other Death in the Family