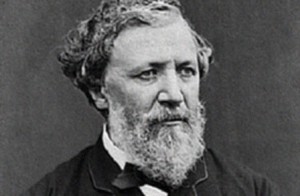

Back in February I wrote about a love sonnet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Today, I’m analyzing a poem by her husband, Robert Browning, who was also a famous poet. The poem is called “Prospice,” which is a Latin term meaning to examine the future, or look toward the future. The title is fitting for the poem, which is the author’s conceptualization of death. Browning views death as the final battle in life, but it is a challenge he accepts fully.

He opens the poem with the question, “Fear death?” (1) as if to mock the typical fright that people associate with it. He describes a kind of storm that leads him to this final event in life: “When the snows begin, and the blasts denote/I am nearing the place…the post of the foe” (2-3). Though Browning refers to death as “the foe,” he does so in order to, once again, portray the common misconception most people have concerning death. Browning continues this metaphor with the lines, “Where he stands, the Arch Fear in a visible form,/Yet the strong man must go” (4). By capitalizing “Arch Fear,” the poet personifies death as “a visible form,” something concrete and real. However, Browning is ready to face him, for “the strong man must go.”

Robert Browning paints death as a glorious battle that transpires after we have conquered life: “For the journey is done and the summit attained…Though a battle’s to fight ere the guerdon be gained” (5-6). “Guerdon” means “reward,” and thus we must triumph over death in order to achieve our final peace. Browning is more than willing to take this on: “I was ever a fighter, so—one fight more,/The best and the last!” (7). Death is the “best” fight, because it gives us the highest recompense. Browning elaborates on his excitement:

I would hate that death bandaged my eyes, and forbore,

And bade me creep past.

No! let me taste the whole of it, fare like my peers

The heroes of old (8-9)

The author doesn’t want death to merely let him past; he is eager to fight, wants to “taste the whole of it,” because it means he will enjoy his victory that much more. He wants to be like “the heroes of old.” Browning explains this, stating, “For sudden the worst turns the best to the brave” (11). In an instant, the terrifying prospect that is death is over, and leads to “the best,” the afterlife, for those that are willing to face death. Because, as Browning says, the end result is something worth fighting for. He imagines it as reuniting with his wife, who has passed away:

…the elements’ rage…Shall change, shall become first a peace out of pain,

Then a light, then thy breast,

O thou soul of my soul! I shall clasp thee again,

And with God be the rest! (12-14)

All the tumult that surrounds the battle with death soon “change[s],” evolving into a “peace,” then into “a light” that guides us, finally, to our loved ones. To Browning, death may be a battle, but it is one that is over quickly, and which ends with such an amazing reward that it is worth enduring.

“Prospice” by Robert Browning

“Prospice” by Robert Browning

“Other Side” Documents Woman’s Fight To Die As She Wishes

“Other Side” Documents Woman’s Fight To Die As She Wishes

The Other Death in the Family

The Other Death in the Family