Wound in lights, heavy with ornaments and heirlooms, photos of children now grown up or parents no longer here, the Christmas tree brightens the living room. It fills the floor with needles and scents the air with pine. Becomes a vigil for the growing crowd of loved ones now with us only in memory. Soon it will be taken down, the decorations packed—but not yet. Just one more evening in its glow.

Wound in lights, heavy with ornaments and heirlooms, photos of children now grown up or parents no longer here, the Christmas tree brightens the living room. It fills the floor with needles and scents the air with pine. Becomes a vigil for the growing crowd of loved ones now with us only in memory. Soon it will be taken down, the decorations packed—but not yet. Just one more evening in its glow.

In James Merrill’s poem, “Christmas Tree”, the tree personifies the poet’s final adieu. Once “brought down at last / From the cold sighing mountain,” he resigns himself to the end and accepts, not with lament, but with grace and poise, “That it would be only a matter of weeks, / That there was nothing more to do” (7-8). What lies in store is a holiday spent wrapping the tree in grandeur as it makes its way to the end.

Prior to the poem’s composition, Merrill had undergone blood tests to determine why he had been losing weight. He later wrote in a diary: “the answer is ARC.” AIDS Related Complex. This was the closest he ever came to writing down the cause of his death. He did not dwell on why he was going to die, but on how—teeming with the treasures and memories collected over a lifetime.

Likewise, the tree does not languish on sorrow, but instead looks to the end as a great summation of a life well lived. For Merrill, a beautiful death is a good death:

Over me they wove a spell of shining—

Purple and silver chains, eavesdripping tinsel,

Amulets, milagros: software of silver,

a heart, a little girl, a Model T,

……………………………………………………………..

Somewhere a music box whose tiny song

Played and replayed I ended before long

by loving. And in shadow behind me, a primitive IV

To keep the show going.” (15-24)

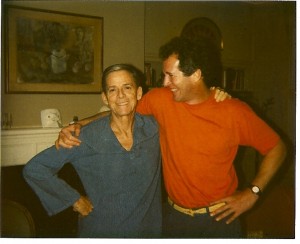

Merrill (left) with his lover Peter Hooten (Credit: Judith Moffett, www.judithmoffett.com)

Rich and ornate, the decorated tree as a death’s head hardly seems undesirable. But the “primitive IV” (the power cord for the tree) is an allegory for the ominous implications of Merrill’s end of life. In his diary, Merrill wrote moving speeches to his lovers: “What face should death wear if not that of perfect love?” Yes, the family may celebrate the tree, but they also cut it down from the start; love and death are merely masks worn by the same face.

But Merrill affirms life until even the last few minutes, the glory of which he does not allow the coming death to diminish. A reconciliation between love and death, the poem ends on images of warmth:

No dread. No bitterness. The end beginning. Today’s

Dusk room aglow

For the last time

With candlelight.

Faces love-lit,

Gifts underfoot.

Still to be so poised, so

Receptive. Still to recall, to praise. (31-38)

Though the two are from the same source, Merrill chooses the mask of love over that of death. And although death and the holidays are inseparable, he shows us how we can look to tradition and ritual to commemorate lost loved ones with dignity and celebration. The best way to conquer what waits for us all is to praise the passing moment, even on this last night, before the tree is removed and the needles swept away.

More from SevenPonds:

- James Merrill on grief

- Wallace Stevens on grief

- Dealing with Death During the Holidays: an Interview with Brad Leary

“Christmas Tree” by James Merrill

“Christmas Tree” by James Merrill

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville