Nobody cares for flowers.

Nobody cares for birds.Nobody wants to believe that Little Garden is dying,

Nobody wants to believe that Little Garden’s heart-

is swollen in this parching heat.Nobody wants to know that Little Garden’s mind-

is slowly losing its green past.And it seems that Little Garden’s sense is a distinct piece,

perishing fast, in the isolating scent of the air.Our courtyard is feeling lonely.

Our courtyard is yawning-

in hope of a possible visit from a raining cloud.Our pool is drained.

And young, tiny leaves-

are collapsing from the heights of the trees.And from the pastel windows of the cage,

song of the birds breaks suddenly-

into the attacks of coughing.

Our courtyard is feeling lonely.

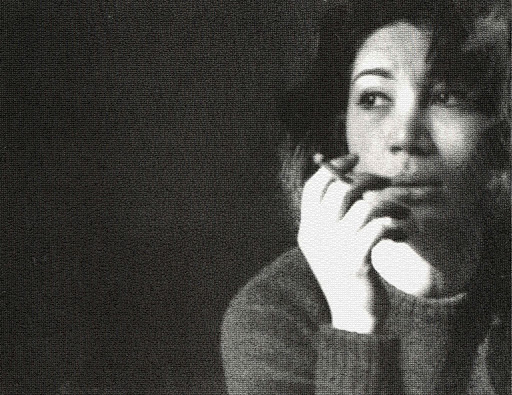

Before her untimely death in a car accident in 1967 at age 32, Forough Farrokhzad became one of Iran’s pre-eminent writers and developed a body of work characterized by her raw expressions of female emotions and passions, which opened her to ridicule from critics and the sexism of her time. It also made her a literary icon whose profound effect has lasted decades.

“Many people who left Iran in the 1980s took three books with them: Saadi, Rumi, Forough,” Iranian poet Fatemeh Shams, also an assistant professor of Persian literature at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times for their “Overlooked” obituary series.

Farrokhzad was born in 1934 to an upper middle-class family; her father, Mohammad Farrokhzad, was a colonel, and her mother, Turan Vaziri-Tabar, a homemaker. She began writing in 1952 after the birth of her first child and marriage to her first husband, a distant relative 15 years older than her named Parviz Shapur. She divorced Parviz in 1954 and released her first published book of poetry around that same time.

That collection contained the poem “Sin,” in which her frank writings on a love affair caused controversy among Tehran’s literary circles and prompted Parviz’s family to restrict her visitation rights with her son. This separation would continue to be a source of great sorrow and despair for Farrokhzad, and that same year she was hospitalized in a psychiatric facility where she received electroshock therapy.

In the years that followed, Farrokhzad would never waver in her commitment to her art, publishing five books of poetry and creating an award-winning documentary film, “The House Is Black,” on her 12-day stay in a leper colony. However, her personal troubles continued, including the inability to see her own son, who was raised to believe that she had abandoned him, and she attempted suicide for a second time in 1960. She survived and would live until she was killed in a car crash in February 1967. Her death made the front page of Iran’s newspapers and was declared a national tragedy.

Farrokhzad battled sexism and personal strife while writing her landmark poetry. Credit: farrokhzadpoems.com

As a woman in a time of great social upheaval in Iran, she grappled with her place in a rapidly westernizing culture that was at odds with the assumed roles of women, which also separated her from her only biological son.

In her poem “I Feel Little Garden’s Pain,” she connects a withering garden to her own sense of despair and grief.

Nobody cares for flowers.

Nobody cares for birds.Nobody wants to believe that Little Garden is dying,

Nobody wants to believe that Little Garden’s heart-

is swollen in this parching heat.

Farrokhzad’s and the garden’s suffering is met with indifference, willful or unconscious, from her family who have resigned to their own busy lives. Her father and mother retire to their rooms after “having done their work,” her brother seeks out distraction and entertainment, and her sister now lives in a “sham house” with perfumes and potions to insulate her from the dust of the little garden.

“Little Garden” is a cry of despair from the only source of life in the work. Her brother wanders stone streets at night, and her father reads dusty books. Her life is in direct contrast to the plastic plants that her sister owns. Farrokhzad’s desire to live freely has left her isolated from her son and family, unable to pull a drink from a cloud passing overhead. The poem has no happy ending, bleakly echoing the first lines:

And Little Garden’s heart is swollen in this parching heat.

And Little Garden’s mind is slowly losing its green past.

Farrokhzad eventually wrote her way into longevity. Her works survived book bans after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. She even found some semblance of a family after adopting one of the boys in the leper colony she had met while filming “The House Is Black.” While her sudden, tragic death robbed the literary world of one of its great futures, the scholars and intellectuals that carried her work after fleeing Iran managed to maintain the Little Garden and retain its green past.

Read the full poem translated by Maryam Dilmaghani on poetrynook.com.

“I Feel Little Garden’s Pain” by Forough Farrokhzad

“I Feel Little Garden’s Pain” by Forough Farrokhzad

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying