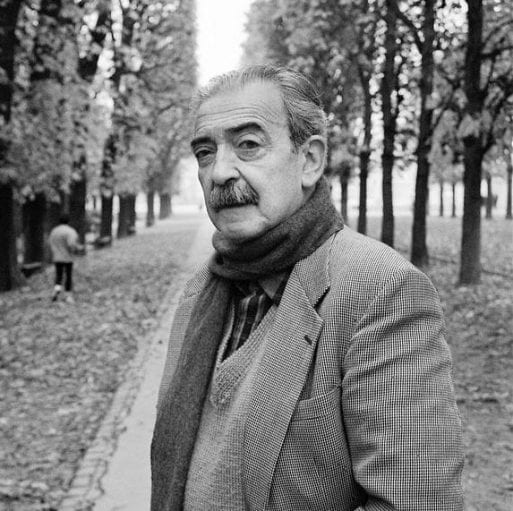

Juan Gelman

For the last thirty years of his life, the work of late poet, political analyst and political exile of Argentina’s Dirty War Juan Gelman grappled with the themes of grief and loss. From 1976 to 1983 a CIA-backed military Junta waged a war of state-sponsored terrorism against the civilian population of Argentina. The Junta mission was to eradicate “political subversives”- people in any way aligned with leftist, socialist or social justice causes. From 1976-1983 the Junta abducted, incarcerated, tortured and murdered 30,000 civilians, who became known as desaparecidos (“the disappeared”).

Soon after the Junta seized control of the country, Gelman’s daughter, his son, and his daughter-in-law were abducted and taken to secret detention centers. His daughter was released after three days, his son and daughter-in-law-who was seven months pregnant at the time of her abduction- were tortured and killed over the course of several months.

In a much cited passage in his essay “Cultural Criticism and Society” (1949), German philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today.”

Juan Gelman, who passed away in 2014 at the age of 83 in his adopted homeland of Mexico, had a slightly different take on the matter of poetry and mass atrocities. Gelman’s is a poetics of resistance and reparation, shaped by a lifetime of witnessing those in power perpetrate egregious human rights abuses and a lifetime of creating an inventive poetic language to make sense of the world and to connect.

In 2000, when he accepted the the Juan Rulfo Prize for Latin American and Caribbean Literature, Gelman spoke in defense of poetry:

“Thedore Adorno once coined an unhappy phrase: He said that it wasn’t possible to write poetry after Auschwitz. For years I’ve though there was an error, that surely Adorno had to have meant ‘like before,’ that it’s not possible to write poetry like the poetry before Auschwitz, or before Hiroshima and Ngasaki, like before the Argentine genocide. And now I think that there is no after Auschwitz, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, after the Argentine genocide, that we exist in a ‘during,’ that massacres are repeated over and over again in some corner of the planet, that there exists a genocide called hunger that kills more slowly than the gas chamber but is no less brutal, that in the last half a century there has not been a single day without war on this earth … And yet, poetry endures, maybe because it finds, like Juan Rulfo said, that the scent of the people smells of hope … Poetry, charred tongue, had to suffer deadly passages in our South, had to make those crossings and escape, not unscathed, but richer.”

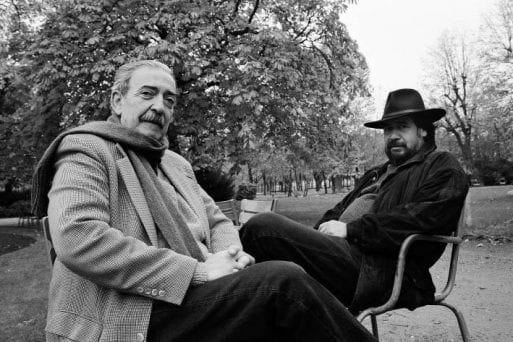

Juan Gelman with Luis Sepulveda,

Chilean writer, activist, and exile of the Pinochet regime

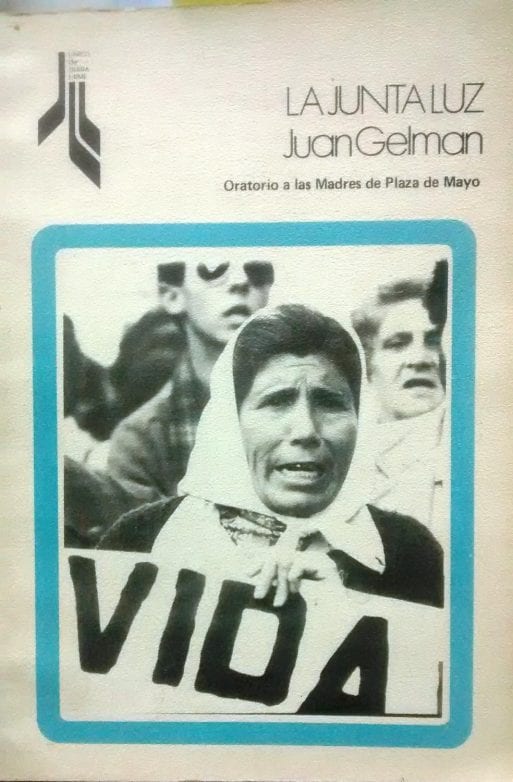

In 1985, two years after democracy was restored to Argentina, Gelman released “La Junta Luz: Oratorio a Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo,” a book-length poem dedicated to the globally recognized group of Argentine mothers who risked their lives during the Dirty War to campaign on behalf of their disappeared children. Beginning in 1977, mothers of the disappeared began organizing weekly non-violent demonstrations in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, the site of Argentina’s most important political institutions. Wearing white head scarves embroidered with the names and dates of birth of their disappeared children, the mothers would meet every Thursday at 3:30 in the Plaza de Mayo and march around the Pirámide de Mayo, the national monument in the center of the square. Every week, the Madres would gather to demand information and to protest the junta’s denials of their children’s very existence.

The Madres de Plaza de Mayo were the first to publicly challenge the brutal dictatorship and to organize against the junta’s human rights violations. They held their weekly demonstrations in public defiance of the junta’s law against mass assembly. The mothers also began an international campaign to defy the propaganda distributed by the military regime. As the numbers of women whose children had “disappeared” grew, and the mothers got more global media coverage, human rights groups arrived to help them open up an office, publish their own newspaper and learn to make speeches.

Juan Gelman wrote “La Junta Luz: Oratorio a las Madres de Plaza de Mayo,” in the language he believed in the most: poetry. Gelman remained in awe at the power of poetry his entire life. By the time he died, he had published 20 books of poetry and had been awarded the Cervantes Prize, the most important in Spanish literature. He knew well the limitations of language in describing the ghastly horror of personal trauma, and remained devoted to poetry as a tool for conjuring possibility into existence and for achieving true connection. “Poetry is the movement towards the Other, it seeks to occupy a space where the other doesn’t exist,” he said in his acceptance speech for the Juan Rulfo Prize. “La Junta Luz: Oratorio a las Madres de Plaza de Mayo,” is Gelman’s movement towards an Other (the mothers of the disappeared) — who shared with him the most intimate, unspeakably horrific and specific trauma of his and their lives — the disappearance of one’s children by a brutal dictatorship running one’s country.

“La Junta Luz: Oratorio a Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo” is a poem written in the form of a script for a staged musical, complete with stage directions. All of the lines of poetry are written to be sung or said by a different character: a disembodied voice offstage, a son (of the tree of life), individual mothers, a disappeared son, a mother-tree character, one of two buddy military thugs, a girl who has been sexually assaulted by soldiers, or the chorus of the collective Madres de Plaza Mayo.

Madres de Plaza de Mayo confront soldiers

Credit: prensa-latina.cu

The tone throughout “La Junta Luz” ranges from distraught to euphoric to righteously enraged to esoteric. The poem-musical is set in the Plaza de Mayo, where the Madres are gathered, surrounding Gelman’s stand-in for the Pirámide de Mayo. In “La Junta Luz,” the hub of the Madres’ activity is the tree of life, which doubles as the national monument.

The lines sung by the mother-chorus are often boots-on-the-ground descriptions of the Madres’ protests and the rage of a devastated mother:

mother-chorus:

I claim you/

every Thursday I hit the dictator’s jackboots with your name/

I put a little white handkerchief on my head/

like you/the dictator doesn’t see my tears, won’t ever see

my tears for you/I hit him with my

fury for you/

Other times the lines read like an incantation:

mother-chorus:

you initiated me in you/your little canary

you navigated the world for me

your little tongue dried my tongue/

I burned in your humidity/

you sweetly opened my doors/

your little feet stepped inside my eternity/

we were the something else/we were something else

In one scene, Gelman’s stage directions are as follows:

(in the background: mothers silently protesting all around

the tree of life. A giant cardboard statue of the dictator, carried by military junta thugs with donkey heads, goes by. The mothers show their breasts. The statue from the back shows flanks, chapped, it tilts to the side and collapses. The mothers hold up a poster that says:”there is no useless pain”)

Sometimes, the imagery gets psychedelic, with big plush green bears walking by, evoking both childhood and the sometimes hallucinatory experiences induced by trauma of the magnitude the Madres and Juan Gelman faced.

La Junta Luz: Oratorio a Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo

Credit: abebooks.com

“La Junta Luz: Oratorio a las Madres de Plaza de Mayo” is a wildly creative and stunningly beautiful expression of grief, written by one of Latin America’s poetry giants. Gelman was celebrated for his wordplay and neologisms of his language. The poet was wont to blend words, adding unorthodox suffixes and prefixes to words to turn nouns into verbs or create compound nouns. Lisa Rose Bradford, who translated Gelman’s “Public Letter,” calls his linguistic inventions “in-between words.”

Of the words he created, which he described as “amphibian,” Gelman said:

These new words, are they not a victory against the limits of language? Does the air not continue to speak to us? And the sea, the rain, don’t they have a myriad of voices? How many words yet unknown are keeping their silence? There are millions of nameless places, and poetry works to name what is still unnamed.

Though he was one of Latin America’s most important and celebrated poets of the 20th century, the unique challenges posed by translating Gelman’s neologisms and rhythmic particularities mean that there is much of Gelman’s body of work that has not been translated. While there is currently no published English translation of “La Junta Luz: Oratorio a Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo,” English speakers who want to familiarize themselves with Gelman’s body of work over the course of 30 years can refer to “Unthinkable Tenderness” — the most representative collection of his poems that exists in English.

“La Junta Luz: Oratorio a Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo” by Juan Gelman

“La Junta Luz: Oratorio a Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo” by Juan Gelman

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”