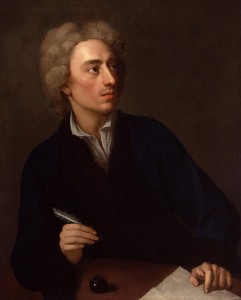

Alexander Pope was highly religious (he was Catholic, despite living in England during an era that was very anti-Catholic), so it’s not surprising that his piece, “The Dying Christian to his Soul,” is filled with spiritual references. As its title suggests, the poem centers on a dying individual that is addressing his soul directly, and his perception of death:

Vital spark of heav’nly flame!

Quit, O quit this mortal frame:

Trembling, hoping, ling’ring, flying.

O the pain, the bliss of dying!

Cease, fond Nature, cease thy strife.

And let me languish into life.

Hark! they whisper; angels say,

Sister Spirit, come away!

What is this absorbs me quite?

Steals my senses, shuts my sight,

Drowns my spirits, draws my breath?

Tell me, my soul, can this be death?

The world recedes; it disappears!

Heav’n opens on my eyes! my ears

With sounds seraphic ring!

Lend, lend your wings! I mount! I fly!

O Grave! where is thy victory?

O Death! where is thy sting?

The dying man urges his soul to leave: “Vital spark of heav’nly flame!/Quit, O quit this mortal frame” (1-2). Pope already makes a reference to heaven, and he is anxious for his soul to go there. He wants to leave this merely “mortal” existence and go on to something greater. Pope elaborates on this concept in the next few lines: “Trembling, hoping, ling’ring, flying,/O the pain, the bliss of dying!” (3-4). Though the man is nervous, he is also excited, and he uses two contrasting words, “pain” and “bliss,” to convey the myriad emotions he is feeling all at once. The poet continues, “Cease, fond Nature, cease thy strife,/And let me languish into life” (5-6), which shows that he is eager to escape and be free of this world.

In the second stanza, not only the dying man himself, but angels too are calling for his soul to go to heaven. They plead, “Sister Spirit, come away!” (8); there is a sense of community in the afterlife, even before the man has died. Next, the narrator describes the sensations he’s experiencing and wonders if it really is death: his “senses” are “st[olen]” (10), his “sight” is “shut[]” (10), and his “breath” (11) is literally taken away. He is totally lost in it; it “absorbs [him] quite” (9).

The final verse describes the man’s last few moments of life: “the world” (13) goes away, and “Heav’n” (14) becomes visible to him. He hears “seraphic” (15), or angelic, sounds all around him, and he “fl[ies]” (16) upward. The narrator is completely happy, and he wonders why death is not as miserable as people often say it is; he questions why his “Grave” (17) doesn’t feel triumphant, and why “Death” (18) isn’t as painful as he thought it would be. Overall, the experience is far more painless than he expected, and he gets to go to heaven, the way that he wanted. Although this is a very Christian view of death, it shows that death doesn’t have to be the sad, painful event that so many individuals believe it to be. Perhaps there is “bliss” in it after all.

*Alexander Pope Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Related Reading:

- More on the Christian view of death

- “Tobi Kahn Creates Art to Make the End of Life Beautiful” (SevenPonds), about how one artist’s work is inspired by his religion

“The Dying Christian to his Soul” by Alexander Pope

“The Dying Christian to his Soul” by Alexander Pope

How To Dispose of a Body In Space

How To Dispose of a Body In Space

AMA Adopts New Policies Expanding Access to Palliative Care

AMA Adopts New Policies Expanding Access to Palliative Care