Tony Kushner’s Angels in America is almost too big to discuss: a sprawling three-part, six-hour play ambitiously covering themes ranging from love and abandonment, to homosexuality and Mormonism, to faith and religion, to disease and dying, to politics and justice, to progress and the very meaning of millennial America.

Tony Kushner’s Angels in America is almost too big to discuss: a sprawling three-part, six-hour play ambitiously covering themes ranging from love and abandonment, to homosexuality and Mormonism, to faith and religion, to disease and dying, to politics and justice, to progress and the very meaning of millennial America.

Undoubtedly, too many to focus on here. So I’m limiting my discussion to Kushner’s moving, unflinchingly honest portrayal of slow deterioration from terminal illness, and the representations of heaven (and hell) as envisioned by various characters facing their own mortality.

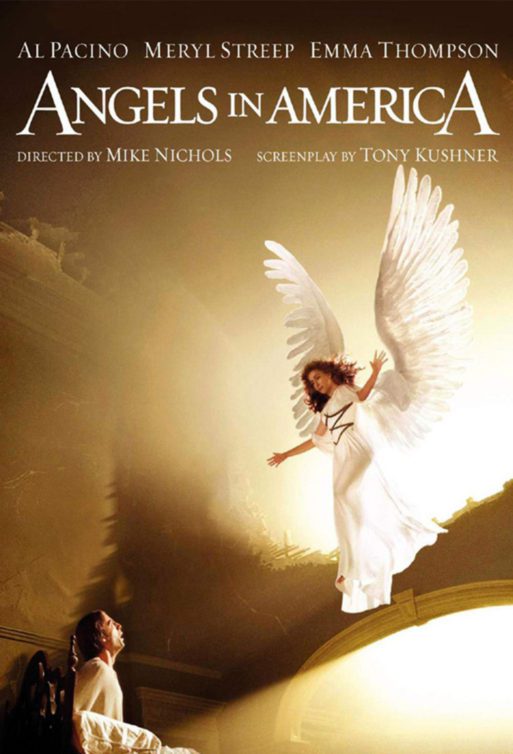

Note: I highly recommend the 2003 HBO miniseries version of Angels in America, directed by Mike Nichols and starring Meryl Streep, Al Pacino, and Emma Thompson. Much of the imagery here will be taken from that version, as I’ve never had the privilege of seeing the play in its entirety.

Pryor Walter, the work’s central character, is a young gay man from a prominent WASP-ish family, living in New York City in the 1980s, who has just been diagnosed with AIDS.

His partner, Louis, is terrified of illness and death, and effectively abandons Pryor in his hour of most dire need. Pryor’s crisis is then bigger than his failing physical health– his crisis is an implosive undermining of his faith, his love, and his capacity to believe in anything. This begins to manifest itself in a series of terrifying visions, in which an angel (the angel of America) visits him at night and proclaims him a true American prophet, like Joseph Smith before him.

Pryor’s best friend, Belize, a flamboyant nurse of Afro-Caribbean descent, remains one of his sole caretakers and close friends after Louis’s abandonment. As Pryor continues on his downward mental and emotional spiral, Belize takes him to the funeral of a prominent area drag queen, another victim of the worsening AIDS crisis. The funeral is a jubilant, raucous celebration with a full gospel choir, dancing, and outlandish costumes. Pryor is horrified. “That was tawdry,” he proclaims; Belize disagrees. “It was divine.” Pryor, wrapped in a black cloak and increasingly eccentric in manner due to his nightly visions, refuses to embrace the possibility of death– to him, simply another of life’s betrayals– and the celebration strikes him as, perhaps, sacrilegious. It’s not until the end of the play, after he has wrestled with his angel, that Pryor finds peace.

Notably, one of Belize’s AIDS patients is the infamous (real-life) conservative lawyer Roy Cohn, checked into the hospital under pretense of “liver cancer.” Cohn rejects the gay community absolutely, because they are powerless, at the bottom of the social pyramid– he argues instead that he’s just a straight guy “who f***s around with guys.” Naturally, Belize and Roy hate each other.

Belize (Jeffrey Wright) cares for Roy Cohn (Al Pacino), despite his intense dislike. Photo credit: Entertainment Weekly.

One night, when Roy has wandered out of his hospital room in a drug-induced haze, Belize catches him in the hallway. Roy puts to him a question: “What’s it like, after?”

Belize’s reply:

“Like San Francisco… Overgrown with weeds, but flowering weeds. On every corner a wrecking crew and something new and crooked going up catty corner to that. Windows missing in every edifice like broken teeth, fierce gusts of gritty wind, and a gray high sky full of ravens… And everyone in Balencia gowns with red corsages, and big dance palaces full of music and lights and racial impurity and gender confusion. And all the deities are creole, mulatto, brown as the mouths of rivers. Race, taste and history finally overcome. And you ain’t there.”

Roy shudders. “And heaven?”

“That was heaven, Roy,” Belize replies sardonically.

Meanwhile, Pryor is taken to the hospital after collapsing in the Mormon Visitors Center, and during his unconsciousness he is summoned to heaven by the angel. Pryor’s heaven is similar to the way Louis described it, in an idle conversation the two had before he left: a perpetual rainy afternoon in autumn. In the film version, heaven is shot at Hadrian’s Villa outside Rome, a former emperor’s complex of Italianate gardens filled with pools, columns, and partly-broken Roman statuary, filtered into black and white.

Heaven, then, is in the eye of the beholder. Belize hates America, in all its racist, unjust, homophobic, diseased glory. For him, heaven is the place where he would no longer be excluded, a beautiful and messy collage of diversity and love. For Roy, that’s the hell he’s trying to keep America from becoming.

And for Pryor, heaven is seen through the eyes of the one he loves, Louis, the god who abandoned him. It’s lovely in a melancholy Greco-Roman way. But even as Pryor wanders his imagined heaven, he defiantly demands “more life” of the angels. The diseased, abandoned world terrifies Pryor, but in the end, he fights to stay in it, just for a little bit longer. Heaven can wait.

Check Out: TIME Magazine’s Top 10 On-Screen Depictions of Heaven

“Angels in America” by Mike Nichols

“Angels in America” by Mike Nichols

“In Case You Don’t Live Forever” by Ben Platt

“In Case You Don’t Live Forever” by Ben Platt

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival