Welcome back to our interview with Yoko Sen, the founder of Sen Sound, a Washington, D.C.-based startup that’s working to transform the experience of hospitalized patients and their families through sound. Ms. Sen is a renowned electronic musician and sound alchemist who has been performing professionally since she was 3 years old. The recipient of the Washington Music Association Award for “Best Electronica Artist,” 2011-2012, she also became the first electronic musician to serve as an artist in residence at Strathmore. Today, her focus is on working to decrease noise pollution in hospitals through human-centered sound design.

Kathleen: Can you tell me about your project the Tranquility Room?

Kathleen: Can you tell me about your project the Tranquility Room?

Yoko Sen: Certainly! The Tranquility Room was a project that I developed in conjunction with the team at the Sibley Innovation Hub. The idea grew out of conversations that we had with hospitalized patients, who often complained that staff spoke too loudly and generally made too much noise. We realized that the conventional approach to these kinds of patient complaints — things like putting up posters in the hallways that said “Shh!! Patients sleeping” or something like that — were largely unsuccessful. They’re condescending, and the staff typically pays no attention to them.

So we decided to approach the problem in a different way. We recognized that people who are stressed and tired and burnt out tend to talk loudly, slam doors and generally make a lot of noise. So we thought, “Why not give the nursing staff a place to relax, either before or during their shift?”

With the hospital’s approval, we took over an empty patient room, and added relaxing visuals, aromatherapy scents and a soothing sound installation. Then we invited the staff to try it out. It was simple and cost effective, and the staff loved it!

Kathleen: What a great idea! Has it continued to be a success?

Yoko: Unfortunately, the hospital has not implemented the idea permanently yet. And that’s ironic, because the prototype happened very quickly and was so successful with the staff. But it’s been over a year and we have run into a lot of bureaucratic red tape — everything from infection control issues to how to secure the room. It’s discouraging to me. But I’m not in a position to push the project — I’m only a consultant. So I have to take a back seat and hope that eventually the hospital follows through.

Kathleen: That’s sad! But then, hospital administrators are not known for being quick to adopt new ideas. Hopefully they’ll get it done for the sake of both the patients and the staff.

Yoko: Yes, I hope so!

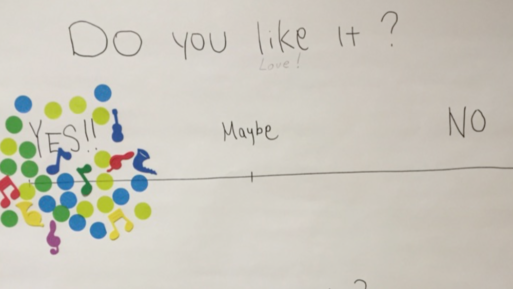

Staff reactions to the Tranquility Room

Credit: sensound.space

Kathleen: Switching gears again: Can you tell me about your project “My Last Sound”?

Yoko: Sure. When I was in the hospital, I often thought about the fact that hearing is reportedly the last sense to go when someone dies. And I wondered how people would answer if they were asked, “What is the last sound you want to hear before you die?”

When I started the project, I collaborated with OpenIDEO, which picked it as a “Top Idea” for its End of Life Challenge in August 2016. We asked the question of people who attended the conference and also on social media and via email. We got hundreds of people to respond.

Then, in September of last year, Stanford Medicine X invited me to collaborate on the project with them, and I was able to record people’s responses as well. Then I used all of the data to create a piece of music, which I presented at the end of OpenIDEO’s Re:Imagine End of Life Conference at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco in October of last year.

Kathleen: That sounds so interesting. Do you have ideas about how to use this information to help people at the end of life?

Yoko: I have so many ideas! Unfortunately, I’m finding that it’s not easy to go from concept to implementation. Finding grant money and other resources can be very difficult, and battling bureaucracy is frustrating.

Kathleen: I’m sure that’s very true.

Yoko: In the meantime I’m looking at my research as a way to get people to open up and talk about what they want the end of their lives to look like. I’ve found that posing the question in this way takes away some of the heaviness of end-of-life discussions and makes them more playful in a way. People think about what sounds they’d like to hear, and that brings up memories of grandma or something from their childhood. It invites stories and sharing and takes way some of the fear.

Recently I gave a talk about the project to a group of 250 hospital CEOs. And if you know anything about hospital administrators you know that they tend to be pretty serious and detached. But by the time I finished my presentation, they were very engaged and very emotional. Hopefully that gave them some idea of how valuable this research can be.

Yoko presents her work

Credit: vimeo.cdn.com

Kathleen: It would certainly seem so! What other projects are you working on in the meantime? I read on your website that you’re doing some work with infants?

Yoko: Yes. I’m just starting a collaboration with a Dr. Jessica Philips-Silver, a neuroscientist who specializes in auditory perception and cognitive development. We call the project My First Sound. We’re researching how the infant brain responds to auditory stimuli with the goal of learning what types of sound are most soothing to infants. We hypothesize that those same sounds would be soothing to people at any stage of life. If that proves true, we can use these sounds in all sorts of clinical settings, from hospitals to hospices to cancer centers.

Kathleen: You’re doing a lot of research. What do you hope to achieve when you have your data and are ready to move on to next steps?

Yoko: That’s an interesting question. Some of my friends say to me, “Yoko, you’re a musician. Just create soothing music and license it to hospitals. You don’t need to do all this research!” But it’s very important to me that my work — the sound I create — is evidence-based. I want to be at the intersection of art, science and design so that I can truly make a difference and alleviate suffering, whether that’s at the end or the beginning of life.

Right now I’m fighting bureaucracy, but I’m from Japan, where the bureaucracy is far worse. So I’m learning to be patient. It may take 10 years, but I believe I’ll succeed.

Kathleen: I’m sure you will!

Yoko: Thank you.

Kathleen: Thank you, Yoko, for sharing your ideas and your research with me. I look forward to following your work and will check back with you soon!

Did you miss the first part of our interview with Yoko Sen last week? If so, please catch up here. And if you’d like to hear some of Yoko’s recording for My Last Sound, watch the short video below.

Would you like to learn more about sound and healing? Check out our interviews with Candace Keach and Silvia Nakkach for different perspectives on healing sounds.

Can Sound Heal? This Musician Believes It Can

Can Sound Heal? This Musician Believes It Can

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?