There is no better poster-child for impressionism than Claude Monet. Even if you don’t know much about Monet, chances are you’ve seen some form of his water lilies on everything from mugs to mousepads.

The French painter was born Oscar-Claude Monet in 1840. Monet struggled with lung cancer and finally died at the age of 86 in 1926. The painter passed away in his now-famous garden estate at Giverny, not too far away from his hometown of Paris. And when he died, Monet left behind a legacy of artistic talent and innovation. Monet played with color and light in a way no one had ever seen before; he embraced the fluidity of the world around him en plein air (outside) and used broad, unrestrained brushstrokes not only to create the composition of a landscape, but to instill in it a sense of true feeling.

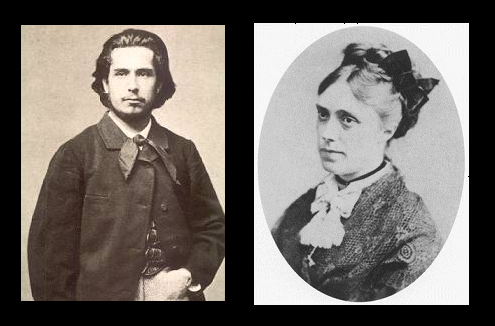

Camille models the latest fashions in Monet’s “The Woman in the Green Dress” (1866)

Credit: wikipedia.com

But Monet could not have achieved half of his fame or success without his artistic muse and counterpart in life, his wife Camille Doncieux (1847–1879).

Camille was described as an assez convenable (quite suitable) wife by Monet’s friend Frédéric Bazille. And it was true, if not an understatement. Camille was a beautiful, well-educated woman who came from a respectable family in the provinces of France. By the time she met Monet in Paris, she had already been modeling for other aspiring artists of the Parisian Salon scene.

Monet and Camille shared the same desire to enrich their lives with all the modernities of 19th century Paris. The world’s first department store, Le Bon Marché, opened its doors here in 1852. The store offered the emerging middle-class a taste of richesse, with new fashions that felt liberating because they combined grandeur with unprecedented accessibility. And Camille modeled them all in Monet’s paintings. Soon, she became known as la reigne de Paris–the queen of Paris.

“Camille Monet sur son lit de mort,” or “Camille on Her Deathbed” (1879) is one of Monet’s most powerful paintings of his wife, if not the most poignant; the canvas captures a real tenderness and unwavering love between Camille and Claude. Towards the end of her life, Camille suffered greatly from dyspepsia and other medical complications that followed the birth of her children. She died at the age of 32, leaving Monet in a state of immense grief which he channeled into a complex piece of art.

“Camille on Her Deathbed” is, in many ways, not much different from another of Monet’s impressionist landscapes; he has captured the fleeting nuances of color as they change with time in a way that’s reminiscent of his many seascapes, or his paintings of Notre Dame. But this time, Camille was Claude’s landscape.”You cannot know,” he said to a friend about painting the picture, “the obsession, the joy, the torment of my days…I was at the deathbed of a lady who had been, and still was very dear to me…I found myself staring at [her] tragic countenance, automatically trying to identify” things like “the proportions of light.” It is a real testament to Monet’s dedication to painting.

But more importantly, it is a testament to the fact that his relationship with Camille was, and would continue to be, inextricably bound to him through his art in a way that transcends death.

“Camille on Her Death Bed” by Impressionst Claude Monet, 1879

“Camille on Her Death Bed” by Impressionst Claude Monet, 1879

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One