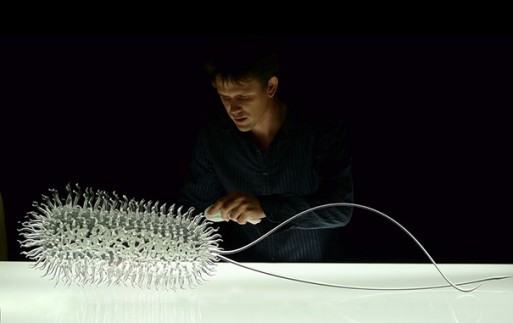

Art, death, microbes, and “the edges of perception” were the dominating topics of artist Luke Jerram’s interview with Scientific American. The UK artist spoke with the online journal about his decision to make glass sculptures of potentially deadly viruses like H1N1, AIDS, Malaria, and others. “I’m interested in how we see the world,” he explained, “[and] consider how the artificial coloring of scientific microbiological imagery affects our understanding of [the AIDS virus]. If some images are colored for scientific purposes, and others altered simply for aesthetic reasons, how can a viewer tell the difference?”

Combine that thought with the fact that Jerram is color-blind, and you get the results of scientific and artistic serendipity: sculptures that bring a transparent yet fantastic perspective of viruses that deeply change the lives of millions.

“For some people,” says Jerram, “the sculptures are personal.” For example, the artist received a passionate, anonymous letter five years earlier from a viewer with HIV who had just seen his AIDS virus sculpture:

Dear Luke,

I just saw a photo of your glass sculpture of HIV. I can’t stop looking at it. Knowing that millions of those guys are in me, and will be a part of me for the rest of my life. Your sculpture, even as a photo, has made HIV much more real for me than any photo or illustration I’ve ever seen. It’s a very odd feeling seeing my enemy, and the eventual likely cause of my death, and finding it so beautiful.

Thank you.

Jerram is a relatively young artist, but already he’s created a range of ambitious pieces that aim to engage the public on a large scale. Years earlier, he trailblazed the famous ‘Play Me, I’m Yours’ phenomenon, which installed pianos in unexpected spaces for public use. He also created the traveling ‘Sky Orchestra’, which “is made up of seven hot air balloons, each with speakers attached…[they] fly across a city [and] each balloon plays a different element of a musical score, creating a massive audio landscape.”

For the creation of his deadly viruses, Jerram consulted virologists from the University of Bristol to make sure the sculptures didn’t miss the mark in their accuracy. “We have to piece together our understanding by comparing grainy microscope images with abstract chemical models,” he explained, “I liaise with the scientists and ask questions [like], ‘How is the RNA packed in? Does it actually look like this or that?’”

The scientific accuracy of the sculptures, which are made of very fragile glass, is an admirable enough feat. But it’s the subtle grace Jerram infuses into their final form and presentation that makes them special. When else would you hear someone describe the AIDS or Swine Flu Virus as delicate or graceful? It takes a risk taker to do that – to see a challenge, explore its complexities, and make it into art.

You may like:

- Friedhof for All: Austria’s Modern Islamic Cemetery

- The Reversible Destiny Foundation: Architecture as an Extension of Life After Death

- Andy Warhol: A Life in Time Capsules

Close Contact: Luke Jerram and the Art of Deadly Viruses

Close Contact: Luke Jerram and the Art of Deadly Viruses

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition