The Annang people of Southeastern Nigeria consider death to be natural only when someone dies of old age, according to Dominic Umoh, Ph.D., a lecturer at the University of Agriculture in Makurd, Nigeria. If someone dies young from disease or violence, they are considered to be “killed” by an evil force. Because these individuals did not live a full, virtuous life as defined by the community they are not eligible to take on the status of “ancestor” when their body dies.

Because ancestors are considered to be teachers and guides for the community of the living, as well as intermediaries between humans and a supreme Spirit, they are placed at the center of family and community life. When an elder who has lived a virtuous life in service to both ancestors and the living dies, a particular funeral ceremony that acknowledges and actively facilitates his transition to the elevated status of ancestor is performed.

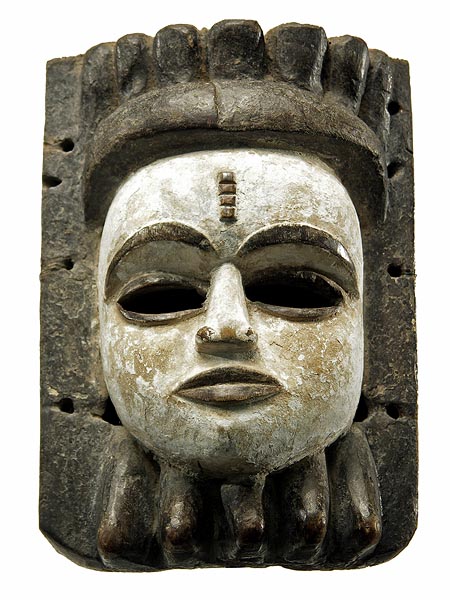

Annang ritual mask

(Credit: hamillgallery.com)

If proper ceremonies are not performed, the Annang people believe that the person’s soul will not find a proper abode in the afterlife and will cause sickness, infertility or other malignant mischief for their family members. However, ancestral spirits tend to be benevolent, watching over family health, abundance and, particularly, fertility, as they will eventually seek reincarnation within their family lineage. This perspective reflects a circular understanding of time, possibly influenced by agricultural cycles, where death is the beginning of another life both materially and on the non-energetic level of consciousness.

Rites of passage are socially constructed ceremonies to help individuals cope with identity-shattering life transitions (such as birth, marriage, passage into eldership) within the context of a community’s existing values, and which serve to reinforce those values. The individual goes through a progression of ritualized events to shed their old identity, thereby assuming a more mature or graduated status within their community. A “rite of passage,” as first coined by Belgian anthropologist and ethnologist Arnold Van Gennep in his 1909 book, “Les Rites de Passage,” has four definitive stages: separation, ritual ordeal, marginality/liminality, and reincorporation.

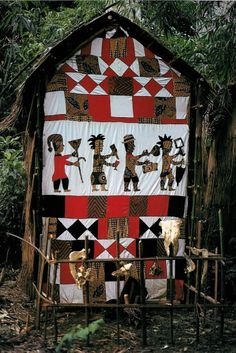

A funeral shrine including a narrative textile

(Credit: pinterest.com)

In the separation phase, the initiate is removed from their daily life and often receives counsel from elders and recognized wisdom keepers; the ritual ordeal facilitates the death of the individual’s old identity; the marginality phase is an important time when the initiate is between identities, neither human or animal, woman nor man, experiencing the fundamental groundlessness behind the order of the human mind; and finally, reincorporation is a time of celebration where the initiate is welcomed back into society with a collectively recognized new status and responsibilities.

Annang burial ceremonies may be understood as rites of passage based on the global, intercultural belief that the body and the mind are related but not the same, and that the mind continues after the body dies. In Annang culture, the community engages in a brief initial stage of intense mourning and wear black clothing immediately following a death — even the death of an elder, because it is recognized that that person is no longer present in their familiar form. This is followed quickly by a second phase of mourning involving lots of spontaneous music and dance, the butchering of animals for ritual and food, and ceremonies to ensure the dead one’s safe passage to the world of the ancestors. Some elements of these proceedings include the creation of a funeral shrine, a homage procession, a “second burial,” and a “Newcomer’s Meal.”

Annang Funeral Tradition as Rite of Passage

Annang Funeral Tradition as Rite of Passage

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States