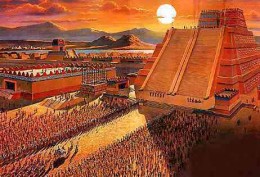

Just as nearly every civilization throughout time, religion played an extremely important role in Ancient Aztec civilization. With over 1,000 gods, 14 heavens, 9 hells, and the sheer ubiquity, intricacy and flamboyance (for lack of a better term) of countless rituals and practices, religion in 16th Century Central Mexico played a role in daily life every bit as defining as Sharia Law in Saudi Arabia, or Puritanism in Colonial America. In the Aztec belief system, the manner of your death was more important than the manner of your life, insofar as it relates to your position in the afterlife. Those who died from natural disaster such as disease, lightning or drowning would go to the paradise of Tlalocan. Those who died from old age or a slow degrading illness would go to the dreary, hellish netherworld of Mictlan. The souls of those who died in battle, or women who died in childbirth, would turn into hummingbirds and fly into the sky where they would follow the sun in its journey across the heavens. Aztec afterlife was dynamic and complicated, and death was by no means the end — or even a resolution. Rather, it was the first step into a drastically changed and sometimes intensely anticipated realm of existence. Human sacrifice, perhaps the most vilified of Aztec rituals, was in fact welcomed by some of its victims as it was considered a sure path to heaven.

Human sacrifice, perhaps the most vilified of Aztec rituals, was in fact welcomed by some of its victims as it was considered a sure path to heaven.

Disposition too would vary according to the manner of death. Those headed for Mictlan — that is, those who succumbed to the less glorious deaths of old age or most types of illness — would be dressed in paper vestments, wrapped in cloth and then cremated, along with a dog, who were considered guides to the afterlife (and these unfortunate souls would need them, as they would have to traverse a truly perilous landscape of winds, mountains and monsters before they reached their destination). Those bound for Tlalocan would be buried whole, along with renderings of powerful mountain gods thought closely related to this more valorous afterlife. And for those considered heroes — pregnant women, fallen warriors and sacrificed lords — bound for the sky paradise of the sun god Tonatiuh, their bodies would be burned in bundles with butterflies and birds, symbolizing their fearsome souls. Annual ceremonies in honor of the dead were performed twice a year for periods of two consecutive twenty-day months in late summer, and many aspects of these ceremonies endure today in the Catholic All Souls’ and All Saints’ Days.

One could probably spend several lifetimes studying Aztec religion and still be nowhere near grasping the myriad of twists and turns of its relations to daily life and its ramifications for your average Aztecan’s behavior and beliefs. But there is certainly something exciting in considering a realm of such dynamism, thought and imagination. Maybe this will help us think about our own deaths a little less statically as well.

Death’s Dynamism in Aztec Civilization

Death’s Dynamism in Aztec Civilization

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento