It was my 18th birthday — five months to the day after my father’s suicide.

It was my 18th birthday — five months to the day after my father’s suicide.

Tears arrived without warning, without my permission. They burst through the protective armor that had been slowly eroding away through my process of denial and minimization.

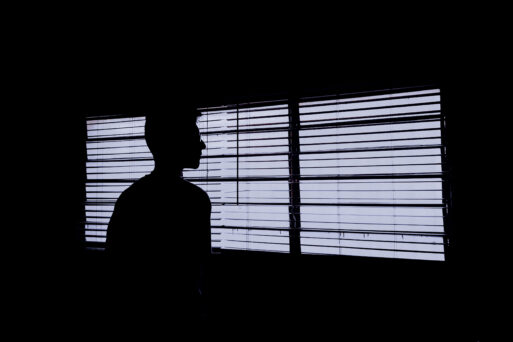

I had thought I held my grief well, the “right way,” strong and silent. I was hiding behind the invincible shield that displayed our family insignia of, “I’m fine.”

But on this birthday, pretense fell away. I fell headlong into the void where no father was there to catch me and say, “Happy Birthday, pumpkin head.”

Why was I crying? It had been five months — shouldn’t I be over it by now?

I judged my tears harshly and perceived them as weakness.

Everyone else seemed to be fine. But in truth, I never asked how they were out of fear that my truth would be revealed.

I didn’t know they were also hiding behind their own shields.

It took another decade to realize I was angry.

I was angry that my father killed himself.

I was angry that I had to try and understand and be sympathetic of his choice.

I was angry that I was left to live with his decision, not his presence.

I was angry at myself for not being brave enough to tell him I loved him before it was too late.

But wait. How can someone be angry at a dead person, a person whose acute suffering led to a desperate act? Had I no heart?

More self-judgment, until I began to recognize that there are the many faces and phases of grief. And this unfolding journey takes a lifetime.

My first nursing job was on the cancer ward.

Mortality rates were high then. So I became the inadvertent student of those I served as I witnessed their journey of dying, grief and loss.

I saw those who expressed their grief with loud wails and flailing arms.

This kind of externalized grief was foreign to me. Initially, I wanted to run. But I learned to stay and be present despite my discomfort.

I witnessed the judgment when some family members expressed their grief differently than others, whether by demonstrating avoidance, stoicism, beating their chests or crying.

I saw that it was easier to share grief with those who had the same style of grieving.

I saw the guilt and fear that accompanied grief, and I saw the anger.

I recognized that beneath the anger was simply grief and loss.

Lost opportunity. Lost presence. Lost future.

In understanding and accepting these feelings in others, I began to understand and accept them in myself.

By removing my protective shield, I could be more fully present, help others find closure, and help them thoughtfully create the legacy they will leave behind.

Death is hard enough. Things left unsaid or undone is harder.

My work became a healing path for me.

By taking the threads from my initial unraveling from my father’s suicide, I wove a tapestry for my own life, transforming a painful lesson into an opportunity to learn and serve others.

For that I am grateful.

Excerpted from original – Finding the Threads – Unraveling Grief, posted June 16, 2015, on Pathways.

Did you miss the first part of Tani’s story? If so, catch up here.

About Tani:

Tani Bahti, RN, CT, CHPN, offers practical guidance to demystify the dying process. A RN since 1976, Tani has been working to empower families and healthcare professionals to enable the best end-of-life experience possible through education and the development of helpful tools and resources. The current Director of Pathways, Tani is also the author of “Dying to Know, Straight Talk About Death and Dying,” a book that SevenPonds considers one of the most helpful books on the subject available today. Founder Suzette Sherman says, “This is the book I will have at the bedside of my dying parents some day, hopefully a very long time from now.”

Transforming the Legacy of Suicide – Part Two

Transforming the Legacy of Suicide – Part Two

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?