For the last 20 years, Ger “Gerry” Fritz, a civil servant living and working in Amsterdam, has been meticulously arranging three pieces of music, a chapel, and flowers for funerals that no one attends. Every year, between 15 and 20 people die alone in Amsterdam, and their backgrounds are as diverse as our time: drug mules, criminals, the elderly, people found in streets or canals, or those who have cut off all social connections for a variety of reasons. When there is no executor to organize a funeral, the city of Amsterdam takes on that responsibility. Fritz organizes and attends these funerals as a representative of the city, but also as a person who feels strongly that every member of a community contributes something special, and should be honored. The funerals are provided not for the benefit of mourners, of which there are none; as Fritz explains, it’s simply and profoundly “for respect of life.”

For the last 20 years, Ger “Gerry” Fritz, a civil servant living and working in Amsterdam, has been meticulously arranging three pieces of music, a chapel, and flowers for funerals that no one attends. Every year, between 15 and 20 people die alone in Amsterdam, and their backgrounds are as diverse as our time: drug mules, criminals, the elderly, people found in streets or canals, or those who have cut off all social connections for a variety of reasons. When there is no executor to organize a funeral, the city of Amsterdam takes on that responsibility. Fritz organizes and attends these funerals as a representative of the city, but also as a person who feels strongly that every member of a community contributes something special, and should be honored. The funerals are provided not for the benefit of mourners, of which there are none; as Fritz explains, it’s simply and profoundly “for respect of life.”

Several years ago, Amsterdam poet Frank Starik approached Fritz with the idea of adding an original poem to each of these lonely funerals. As a testament to Fritz’s commitment to respect each person as unique and of value, he was at first wary of Starik’s idea. Starik was persistent, and Fritz eventually conceded to the collaboration. To write the first poem, Starik approached Fritz requesting details about the person who died, but Fritz gave him only the bare minimum. Fritz explains that he wished to maintain respect for the dead, which to him meant avoiding any details that didn’t paint the subject in the best light. Inspired rather than deterred, Starik created a simple and moving eulogy for that unidentified person. He writes, “Goodbye, Stranger. I say goodbye. On the road to nowhere, in the final country where everyone is welcomed in. Where no one needs to know your origin. Farewell, Sir without papers, without identity. What were you looking for? How much did you lose along the way?”

This first poem created a bond of trust between the two men, which began a new tradition. Starik was given access to the intimate details of his subjects’ lives, sourced primarily from information gathered by city workers while visiting the homes of the deceased to sort out their bills and put their affairs in order. Starik speaks of his role as a storyteller who returns stories – identities – to people who have somehow lost theirs along the way.

Humans are, after all, social beings, so much so that we can feel kinship and loss for someone who we have never met.

Fritz is now retired, but Starik is still writing commemorative poems. They have since founded an organization called Lonely Funerals, and have invited more poets into their initiative. Starik reflects that this work is a somber reminder that it’s easy for people to be forgotten in a big city without friends or family, and to value community in our lives for that reason. Humans are, after all, social beings, so much so that we can feel kinship and loss for someone who we have never met.

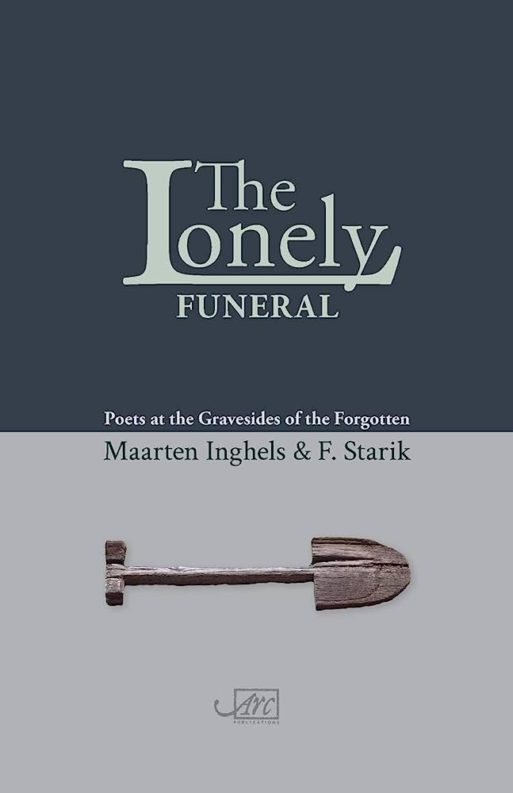

“The Lonely Funeral” by Maarten Inghels and F. Starik

“The Lonely Funeral” by Maarten Inghels and F. Starik

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States