In 2007, Will Schwalbe’s mother, Mary Anne, was diagnosed with hepatitis after returning from a humanitarian trip to Pakistan. Months later, her doctors discovered she was suffering from an advanced stage of pancreatic cancer, a disease which is usually fatal within six months. In The End of Your Life Book Club, Schwalbe follows the story from his mother’s initial diagnosis to her death while they read and discussed a series of books. As avid lifelong readers, Schwalbe and his mother offer interesting insights into the types of books one might read as they approach death and how loved ones can help in a supportive, loving way.

In 2007, Will Schwalbe’s mother, Mary Anne, was diagnosed with hepatitis after returning from a humanitarian trip to Pakistan. Months later, her doctors discovered she was suffering from an advanced stage of pancreatic cancer, a disease which is usually fatal within six months. In The End of Your Life Book Club, Schwalbe follows the story from his mother’s initial diagnosis to her death while they read and discussed a series of books. As avid lifelong readers, Schwalbe and his mother offer interesting insights into the types of books one might read as they approach death and how loved ones can help in a supportive, loving way.

In the beginning of the book, Will Schwalbe is still a publisher with a hectic lifestyle. As he begins to cope with his mother’s diagnosis, he realizes their relationship requires new levels of both honesty and sensitivity. He writes, “Raving about books I hadn’t read yet was part of my job. But there’s a difference between casually fibbing to a bookseller and lying about seventy-three-year-old mother when you are accompanying her for treatments to slow the growth of a cancer that had already spread from her pancreas to her liver by the time it was diagnosed. I confessed that I had no, in fact, read this book” (4). Starting with discussions about books, they are able to move into more difficult talks about their feelings. Ironically, his mother has a habit of reading the endings of books first.

“As he begins to cope with his mother’s diagnosis, he realizes their relationship requires new levels of both honesty and sensitivity.”

It’s amazing how simply Will Schwalbe is able to communicate the step-by-step process of his mother’s decline in a way that enables readers to relate and learn from his experience. Mary Anne Schwalbe seems to be a different character than most in the sense that she is positive during difficult times and incredibly resilient. Schwalbe writes of his mother affectionately, saying, “She kept telling herself and all of us how lucky she was—to have insurance; to have had such a wonderful long life; to have grandchildren she adored and meaningful work… but as she repeated this mantra now, with a slight crack in her voice, I heard something new: fear” (33). He acknowledges the fear in her that effectively makes her human. No matter how bravely she faces her condition, the finality of an incurable diagnosis can’t help but make her and everyone around her reflect on life and death with renewed urgency.

was—to have insurance; to have had such a wonderful long life; to have grandchildren she adored and meaningful work… but as she repeated this mantra now, with a slight crack in her voice, I heard something new: fear” (33). He acknowledges the fear in her that effectively makes her human. No matter how bravely she faces her condition, the finality of an incurable diagnosis can’t help but make her and everyone around her reflect on life and death with renewed urgency.

Several times in The End of Your Life Book Club, Schwalbe contemplates the proper approach for getting his mother to open up about her feelings. Just getting her to talk about her pain seems to be a big step since she, like so many other mothers, doesn’t want to complain too much (even when dying of cancer). He writes, “There’s a big leap from ‘Do you want me to ask how you are feeling?’ to ‘Do you want to talk about your death?’ And even if I was to bring it up, how could I be sure she wouldn’t then talk about it because she thought I wanted to, even if she didn’t?” (100). As he navigates these issues, we are able to learn from his experience. One of his biggest revelations is also my favorite line in the book. “I was learning that when you’re with someone who is dying,” he writes, “you may need to celebrate the past, live in the present, and mourn the future all at the same time” (130). In that way, his preparation for his mother’s death also prepares him to live more attentively. With all of the further reading recommendations we gain from this book we also gain a new perspective on living and dying well.

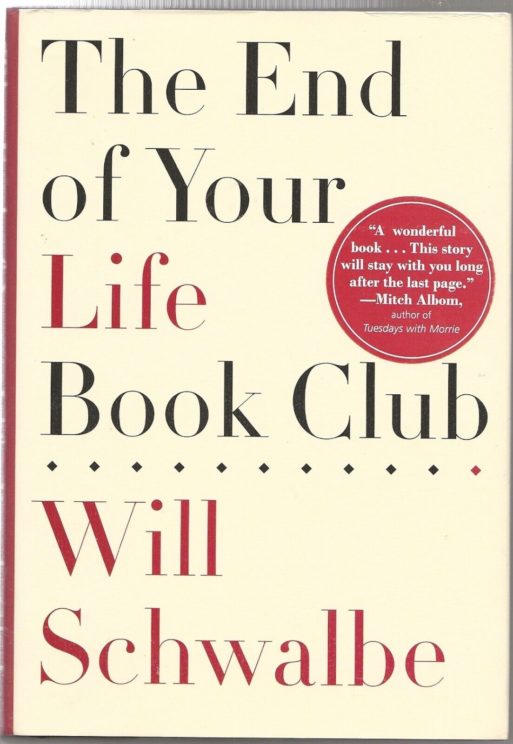

“The End of Your Life Book Club,” by Will Schwalbe

“The End of Your Life Book Club,” by Will Schwalbe

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States