One of my favorite childhood memories is of snuggling up on the living room couch with a good piece of fiction. I was an avid reader. For the most part, reading was my escape from the real world, a world that was impacted by numerous family illnesses and deaths. I usually strayed towards action, mystery, and dystopia — genres that avoided anything too personal — out of fear of feeling heartache. But after coming across Katherine Paterson’s 1977 book “Bridge to Terabithia,” that all began to change. Her timeless classic deals with many of the problems that young people face, including some not usually recognized in children’s literature.

One of my favorite childhood memories is of snuggling up on the living room couch with a good piece of fiction. I was an avid reader. For the most part, reading was my escape from the real world, a world that was impacted by numerous family illnesses and deaths. I usually strayed towards action, mystery, and dystopia — genres that avoided anything too personal — out of fear of feeling heartache. But after coming across Katherine Paterson’s 1977 book “Bridge to Terabithia,” that all began to change. Her timeless classic deals with many of the problems that young people face, including some not usually recognized in children’s literature.

Paterson’s novella touches upon the subjects of death and masculinity through the eyes of a young boy named Jesse Aarons, who is excited to begin his career as the fastest runner in the fifth grade. While his home life contains many of the struggles that lower-class farming families endure, his life at school is relatively dull. His only motivations are his artwork and his favorite teacher, Miss Edmunds.

During a run one morning, Jesse comes across a young girl — his new neighbor, Leslie Burke. The two of them don’t immediately hit it off, since Leslie has proven herself the fastest runner in all of the fifth grade, beating Jesse at a recess race. But eventually, the two become close companions and often accompany each other to their shared imaginary kingdom in the woods, a place called Terabithia.

Credit: archives.hippopress.com

One day while Jesse is out with Miss Edmunds, Leslie decides to go to Terabithia without him, crossing the creek that divides the property by swinging on a rope swing. Leslie accidentally falls and hits her head, causing her to pass out and drown in the creek. When Jesse finds out, he feels guilty that he didn’t go with her in the first place.

“Bridge to Terabithia” is a piece of children’s literature that introduces the concept of death in a very personal, effective way. The omniscient third-person narration allows the audience to experience the story through many different angles while still focusing on Jesse’s personal grieving process. It also allows Paterson’s own voice to come through as she guides the reader through a hard but necessary event. Although the main conflict is the death of Leslie’s character, Paterson also incorporates other facets of childhood grief, such as personal growth, domestic issues and feelings of abandonment. The story concludes that sometimes, when all we think we have left is our imagination, there is always someone there to help us cross the bridge from hurting to healing.

Katherine Paterson

Credit: www.alma.se

I look back fondly on my relationship with this book because it has only deepened over the years. I remember how impressionable I was as a child, and I am grateful that I was introduced to productive, positive ways to handle my feelings rather than destructive, harmful ways. Paterson’s novella is a visual guide on how to cope with the loss of a loved one disguised as a fictional story. I would recommend “Bridge to Terabithia” to parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, anyone who has influence over a child struggling to grasp the confusing emotions that come with death. If it’s hard for us to understand, the journey for children can be even more difficult. After all, in Katherine Paterson’s own words, “You never know ahead of time what something’s really going to be like.”

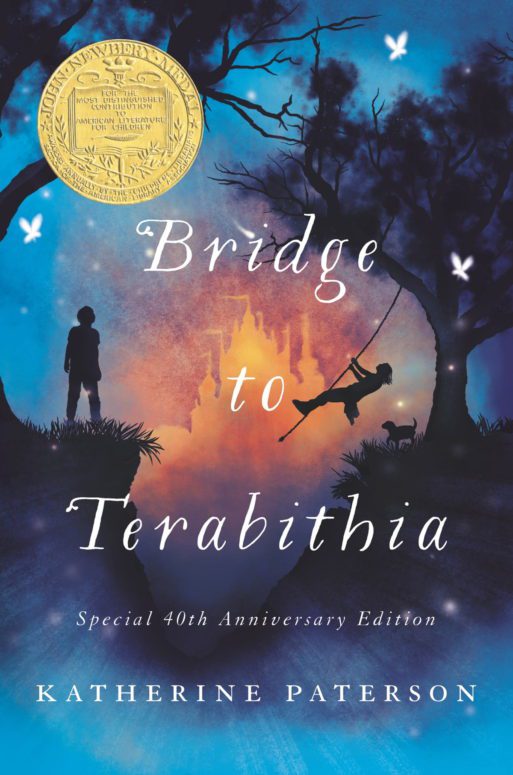

“Bridge to Terabithia” by Katherine Paterson

“Bridge to Terabithia” by Katherine Paterson

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States