In “Grieving While Black,” Breeshia Wade invites the reader to explore the ways that grief and a desire to prevent loss pervade our world and cause division. She writes as a Black woman who was raised Southern Baptist but is now Buddhist, and intertwines her experiences as a hospital chaplain with theoretical explanations of the ways both Black people and other races internalize grief. Wade makes the case that grief is inherent in many of our other emotions, such as anger or a desire for power, but that we rarely take the time to recognize grief as such.

“Grieving While Black” offers a detailed analysis of the ways that social locations such as race impact collective grief and acceptable expressions of grief, sharing, “So let’s start calling anger what it is – a form of grief. When people fear Black women’s anger, what they are really afraid of is the depth of our bereavement.” Wade also highlights the different ways that racial groups are either sheltered from the idea of death or forced to confront it from an early age, writing that

The first death that white parents are likely to talk to their children about is a family pet’s or an elderly grandparent’s. The first death Black parents talk to their children about is their children’s own (and what they must do to try and protect themselves from early death).

Wade speaks to the uncomfortable reality that grief and death are not experienced equally across racial groups and challenges readers to understand the ways that grief becomes weaponized.

Overall, “Grieving While Black” is an illuminating read that speaks to the different types of grief facing communities that are both intimate and more large-scale, from an African-American man whose anxious pacing at his father’s deathbed led to a nurse calling security, to a Native American activist sharing her grief about climate change. Wade’s writing is strongest when sharing personal stories and experiences from her life and chaplaincy. The work becomes slower-going in the middle section when it takes a theoretical turn and drills down on the ways that Wade believes grief interacts with systemic oppression. While I understand the academic arguments she was making, I was left craving more of the storytelling, given her fascinating end-of-life experiences.

Author Breeshia Wade

Ultimately, Wade’s training in Buddhism becomes obvious as she encourages meditative awareness of the griefs we carry with us, large and small, past and future:

We accept that we will lose everything we’ve worked for and have ever loved by virtue of the fact that death, grief, and loss are fundamental parts of our existence. None of us can know how we will lose the things we care about – our careers, our health, our lives. It could be a gradual or rapid decline. But we can guarantee that it will happen.

This book is a helpful reminder that we are always in a state of grieving things we have already lost and will lose in the future, and that society treats grief differently according to racial background. It is not an easy read, but certainly thought-provoking, particularly for anyone interested in more cross-cultural understandings of systemic grief and loss.

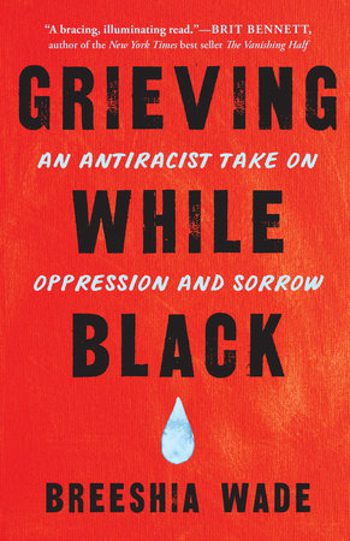

“Grieving While Black” by Breeshia Wade

“Grieving While Black” by Breeshia Wade

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”