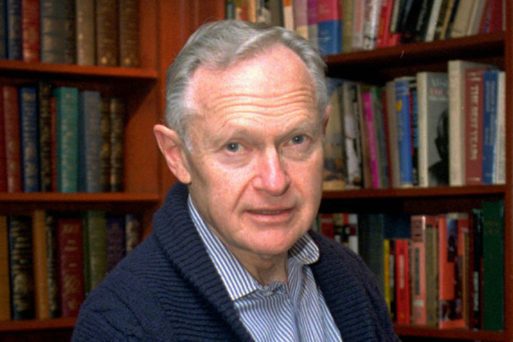

Sherwin Nuland, an accomplished surgeon, wrote “How We Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter” in an effort to reveal the grim realities surrounding death; the fact that “by and large, dying is a messy business.” He was motivated to do so by witnessing how medicine’s drive to prolong life often enhances suffering; how the futile grasp for hope deprives patients and their families of peaceful resolution. The book, published in 1994, won a National Book Award, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and sold over half a million copies — demonstrating a widespread hunger for greater understanding of the truthful circumstances surrounding our deaths.

Sherwin Nuland, an accomplished surgeon, wrote “How We Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter” in an effort to reveal the grim realities surrounding death; the fact that “by and large, dying is a messy business.” He was motivated to do so by witnessing how medicine’s drive to prolong life often enhances suffering; how the futile grasp for hope deprives patients and their families of peaceful resolution. The book, published in 1994, won a National Book Award, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and sold over half a million copies — demonstrating a widespread hunger for greater understanding of the truthful circumstances surrounding our deaths.

Much of “How We Die” explores the specific physiological processes involved various forms of fatal illness — heart attacks, strokes, cancers, Alzheimer’s, AIDS (one chapter argues that old age be considered a valid cause of death, whatever the reason listed on a death certificate). Readers may find these passages intriguing, overly medical, or even disconcerting — someone currently undergoing treatment for such disease may wind up disheartened, while healthy hypochondriacs could find themselves propelled toward the self-diagnostic rabbit hole of WebMD. Yet these passages do serve their function: to demonstrate, for the lay reader, the specific — and rarely pretty — processes that the body encounters as it progresses through terminal illness and death. In addition, Nuland provides fascinating historical background, explaining some of the early impetus for diagnoses and the etymology of medical terms. In some cases, diseases — such as cancer, which eventually claimed Nuland’s life — is personified in frighteningly vivid ways:

Cancer, far from being a clandestine foe, is in fact berserk with the malicious exuberance of killing. The disease pursues a continuous, uninhibited, circumferential, barn-burning expedition of destructiveness, in which it heeds no rules, follows no commands, and explodes all resistance in a homicidal riot of devastation.

Perhaps most engagingly, Nuland offers specific and carefully reported case studies that reveal the emotional impact of these disease processes on both patients and their families. Commonly, Nuland chooses subjects close to his heart: dear friends; patients; even his own brother, Harvey, who died of colon cancer in 1990. The stories in “How We Die” extend far beyond mere anecdotes to explore the deeper impact on individuals, relationships and approaches to medicine. In a surprising confession highly revealing of our common blindness when it comes to end-of-life decisions, Nuland shares how he counseled Harvey to engage in toxic experimental therapies despite years of medical practice that had taught him the futility of such measures.

Perhaps most engagingly, Nuland offers specific and carefully reported case studies that reveal the emotional impact of these disease processes on both patients and their families. Commonly, Nuland chooses subjects close to his heart: dear friends; patients; even his own brother, Harvey, who died of colon cancer in 1990. The stories in “How We Die” extend far beyond mere anecdotes to explore the deeper impact on individuals, relationships and approaches to medicine. In a surprising confession highly revealing of our common blindness when it comes to end-of-life decisions, Nuland shares how he counseled Harvey to engage in toxic experimental therapies despite years of medical practice that had taught him the futility of such measures.

Harvey paid a high price for the unfulfilled promise of hope. I had offered him the opportunity to try the impossible, though I knew the trying would be bought at the expense of major suffering. Where my own brother was concerned, I had forgotten, or at least forsaken, the lessons learned from decades of experience.

Throughout the book, Nuland’s worldview features strongly: In discussing controversial deaths such as medical aid in dying, or stigmatized deaths such as personal suicide, his language leaves little room for open-ended discussion — or sometimes, even empathy. Readers may sympathize more with his unwavering stance after learning that his own life was fraught with depression, illness and death. His 2014 obituary in the New York Times explains how he was hospitalized for more than a year in his 40s due to depression and nearly received a lobotomy; instead, Nuland recovered following electroshock therapy. His mother died from colon cancer when he was 11; his overbearing father, whom he believed suffered from chronic and undiagnosed syphilis, followed her shortly after Nuland became the chief surgical resident at Yale-New Haven Hospital. While Nuland grappled with the fallout of these and other struggles throughout his life, they nevertheless contributed greatly to his work and its continued impact on others.

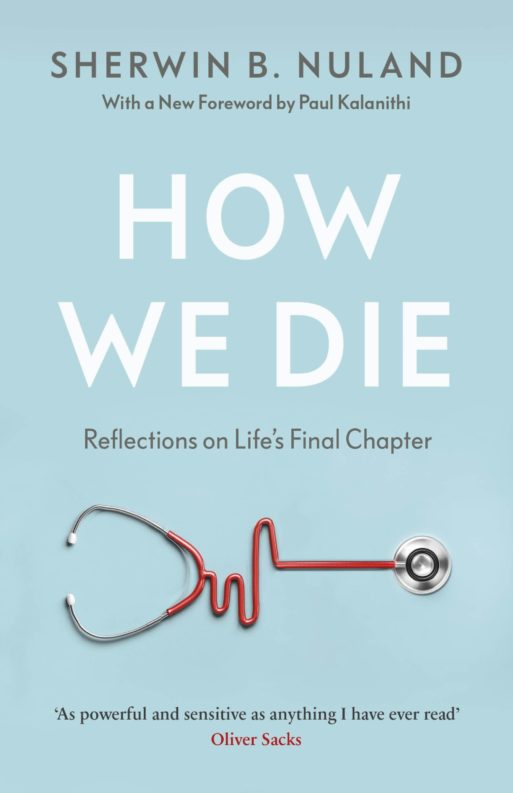

“How We Die” by Sherwin Nuland

“How We Die” by Sherwin Nuland

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”