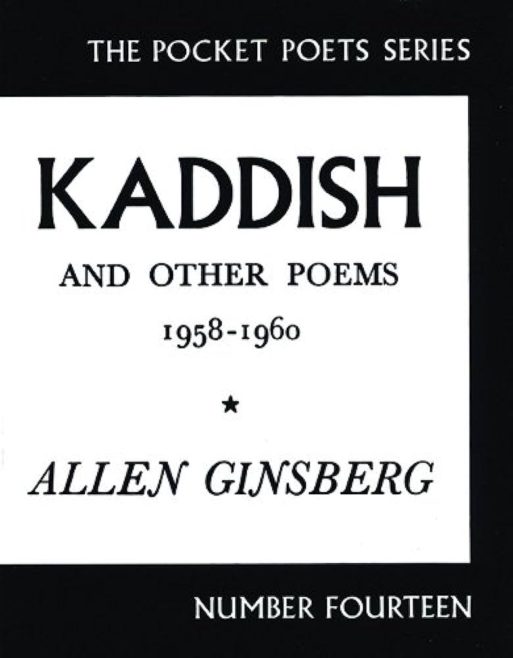

When readers discover beat poet Allen Ginsberg, they often first come across the poem “Howl“. The elegiac rhapsody was (in)famous in its time for its explicit language and an ensuing obscenity trial that, ironically, only threw Ginsberg’s work straight into national public attention. Indeed, the first time I learned of “Howl” was not in English but in History class, and not as a poem but as an important cultural artifact testing the limits of the first amendment. (Others may have watched James Franco recite the poem while starring as Ginsberg in the movie Howl.) But fewer readers go beyond that dazzling masterpiece to discover his second book, Kaddish (1961). The title refers to Jewish hymns in praise of God that are often said as a part of mourning, and in the titular poem, Ginsberg both praises and mourns his mother, Naomi Ginsberg (1894–1956). Wavering from heartbreaking tenderness to visionary rapture, he tells the story of her life, her struggle with madness, her beauty, her ugliness—and her death.

When readers discover beat poet Allen Ginsberg, they often first come across the poem “Howl“. The elegiac rhapsody was (in)famous in its time for its explicit language and an ensuing obscenity trial that, ironically, only threw Ginsberg’s work straight into national public attention. Indeed, the first time I learned of “Howl” was not in English but in History class, and not as a poem but as an important cultural artifact testing the limits of the first amendment. (Others may have watched James Franco recite the poem while starring as Ginsberg in the movie Howl.) But fewer readers go beyond that dazzling masterpiece to discover his second book, Kaddish (1961). The title refers to Jewish hymns in praise of God that are often said as a part of mourning, and in the titular poem, Ginsberg both praises and mourns his mother, Naomi Ginsberg (1894–1956). Wavering from heartbreaking tenderness to visionary rapture, he tells the story of her life, her struggle with madness, her beauty, her ugliness—and her death.

It is by no means an easy story to tell, or to read. He begins by recalling her life in the midst of his chaotic stream-of-consciousness as we walk through New York City, showing how her life contends with, and eventually rises above, the myriad allusions and musings swirling in his mind:

“Strange now to think of you, gone without corsets & eyes, while I walk on the sunny

pavement of Greenwich Village.

downtown Manhattan, clear winter noon, and I’ve been up all night, talking, talking,

reading the Kaddish aloud, listening to Ray Charles blues shout blind on the

phonograph

the rhythm the rhythm—and your memory in my head three years after—And read Adonais’ last triumphant stanzas aloud—wept, realizing how we suffer—

And how Death is that remedy all singers dream of, sing, remember, prophesy as in the Hebrew Anthem, or the Buddhist Book of Answers—and my own imagination of a withered leaf—at dawn—”

In this disruptive storm of literature and music, the force of memory takes control of the poem and we learn about her immigration from Russia, her childhood, and the traumatic course of his family life as she descends into madness and paranoia. She believes the world, including her own husband, is conspiring against her. In turn, Ginsberg’s upbringing is ruptured by her stays in the ward. Many of the images are shocking and brutally honest as young Ginsberg endures her illness more than any son should. But in these chaotic fragments come moments of startling simplicity and quiet beauty. Such was the case when he finds consolation in the knowledge that she is at peace: “There, rest. No more suffering for you. I know where you’ve gone, it’s good.” We get her whole life in all its details, the good and the bad, the horrific and the miraculous.

As the above passage shows, Ginsberg’s exhilarating style shatters the conventions of English and invokes the free-flowing, jazzy stops and starts of his stream of consciousness run amok. Though not always easy to follow, his erratic phrase offers the reader all sorts of surprises. We never know exactly where his thought will go next. But it transcends mere aesthetic gratification and enhances an important feeling and theme throughout the poem. On the back of the book, Ginsberg provides his own introduction written in the same style, saying how “in the midst of the broken consciousness of mid twentieth century suffering anguish of separation from my own body and its natural infinity of feeling its own self one with all self,” he endeavors to generate a spiritual discovery in which all things are one and time is but an illusion. The language, then, “intuitively chosen as in trance & dream,” enhances this “broken consciousness” as it breaks through the self and attempts to comprehend and become a part of eternity. This lofty theme is grounded with the story of his mother, for whom reality and consciousness were malleable and always changing. Inspired by her death, the spiritual theme is therefore incredibly personal. Ginsberg gives us both his mother and himself, with no filter, only the brutal truth.

Because of its density and length, Kaddish requires multiple readings—which is the mark of its quality and depth as a poem. Ginsberg gives us nothing more than complete honesty and sincerity, and the best way we can honor his gift is by swimming through his flood of phrases and feelings again and again. At one point, he wonders,

“O mother

what have I left out

O mother

what have I forgotten

O mother

farewell”

and although memory is imperfect, and we can’t record absolutely everything, he’s given us all the important aspects of her life for us to keep her in our minds as well. May poet and mother alike rest in peace in eternity.

More from Lending Insight:

- Classic Book Review: A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

- Book Review: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson

- Voices Summoned from the Pandemic in Kyrie

“Kaddish” by Allen Ginsberg

“Kaddish” by Allen Ginsberg

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States