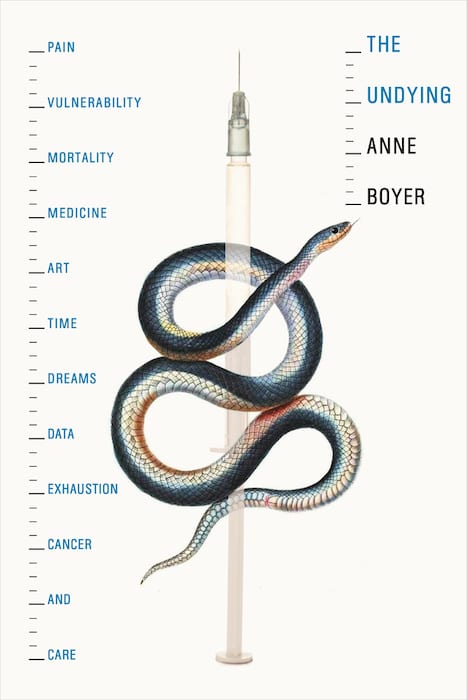

These days, it is practically a truism to say that pain resists language. Whether speaking of psychic or bodily pain, many authors agree that words will never be able to express the reality of such intense experiences. Yet, in “The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care,” Anne Boyer pushes against the boundaries of language to see what words can do. Refusing to accept her pain as inarticulable, she creates a breathtaking book that exceeds generic norms or simple description.

These days, it is practically a truism to say that pain resists language. Whether speaking of psychic or bodily pain, many authors agree that words will never be able to express the reality of such intense experiences. Yet, in “The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care,” Anne Boyer pushes against the boundaries of language to see what words can do. Refusing to accept her pain as inarticulable, she creates a breathtaking book that exceeds generic norms or simple description.

A poet and single mother, Anne Boyer was diagnosed with highly aggressive, triple-negative breast cancer at the age of 41.

I have to say: I found it difficult to write that sentence. It is a sentence that follows a neat form—an encapsulation of someone’s basic social identity, followed by their diagnosis and age at which they were diagnosed—and it can be found at the beginning of nearly any description of someone who has had cancer. But after reading “The Undying,” the very neatness and familiarity of the phrase makes me question the ways in which it falls short.

Author Anne Boyer

Credit: Cassandra Gillig via whiting.org

One of the greatest strengths of “The Undying” is the extent to which it troubles the illness narrative as a literary form, while also drawing on the history of the genre. Rather than follow the climactic arc of discovery, diagnosis, and cure (or death), the book is grouped around loose themes or trains of thought. Boyer ruminates on the ancient “incubants” who attempted to cure themselves through instructions received in dreams, grows fascinated by cancer hoaxers, and explores the textures of exhaustion. Rich descriptions of her treatment appear throughout, but they are non-chronological and refuse to cohere, reflecting the fragmented subjectivity that often comes with cancer treatment. As Boyer writes,

“I do not want to tell the story of cancer in the way that I have been taught to tell it…I would rather write nothing at all than propagandize for the world as it is.”

As this line suggests, Boyer is not at ease with the contemporary world. She insists on acknowledging the ways in which capitalism, racism, and misogyny permeate all realms of life and death—the sanitized walls of a hospital cannot keep inequity at bay.

“Disease is never neutral. Treatment is never not ideological. Mortality never without its politics.”

As a result, topics that are excised from many cancer memoirs make their way into “The Undying,” allowing for a conception of illness that includes the realities of capitalism, politics, and desire.

As someone who has undergone cancer treatment and often struggles to articulate its sensations and significances, “The Undying” has offered me a new lexicon for my experiences. But Boyer’s insights are worth investigating even for those who have not encountered cancer. After all, in Boyer’s words, “every person with a body should be given a guide to dying as soon as they are born.” This may not be an exhaustive handbook to dying, but in its sweeping historical and literary references and elegant prose, “The Undying” is an example of how we might attend to the complexities of life and its end with true care.

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?