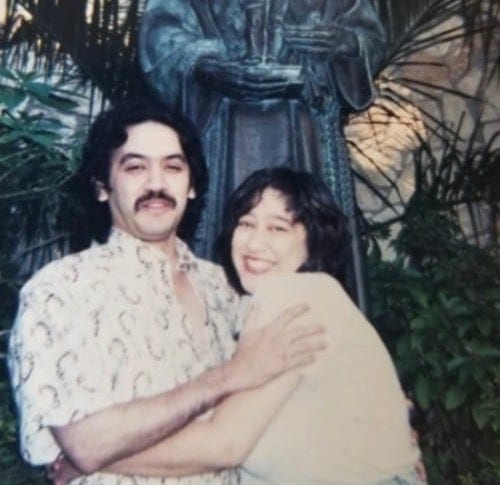

Heather and Carlos on the San Antonio River Walk in 1999

This is the Heather’s story as told to Jeanette Summers. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this story, Heather talks about losing her brother to refractory epilepsy.

My brother, Carlos, who was two years older than me, died of refractory epilepsy: a seizure disorder, otherwise known as uncontrolled, intractable, or drug-resistant epilepsy, that doesn’t respond to medication.

The word “epilepsy” is derived from the Greek “epilepsia,” which means “to take hold of” or “to seize.” Long ago, epilepsy was thought to be a sign of demonic possession; treatment included “drilling the soul to drive out the demons.” Though Carlos wasn’t possessed by evil spirits, epilepsy certainly took hold of him — turned him into a marionette, subject to the whims of a senselessly sadistic puppet-master. He had several seizures a month since we were kids. One came on while he was pressing a pair of pants, forcing him to grapple on the carpet with a scalding iron. Another time, he fell onto a patch of searing-hot Texas asphalt, leaving his face scraped raw.

Refractory epilepsy put my brother’s life in grave danger, and so he lived with my mother and aunt for most of his adult life. When Carlos, at the age of 45, told me that he was planning to move out and live on his own, I knew deep in my bones that he wasn’t going to survive for long.

One month after Carlos’ 46th birthday, I got the call: My brother was dead. As usual, my mother and aunt had called him to check up several times over the course of 24 hours. When he wasn’t answering, they drove to his apartment and arrived to a nightmare-come-to-life: my brother’s bluing body. During a complex partial seizure, Carlos had fallen, face-first, into an open plastic grocery bag and asphyxiated.

When the seizures would come on, Carlos would always try to fight them. But when my mother and aunt found him dead, there were no signs of strain, struggle, or resistance; the muscles of his face had gone slack with surrender. He was at peace at last.

Epilepsy Destroyed His Life

Carlos suffered his whole life. He was a whip-smart boy and had even been enrolled as a pre-med student. But over time, the seizures damaged his brain and stripped him of the intelligence he was born with. Cognitive disabilities replaced his innate quick-thinking and constant anger replaced his once-spunky, easy-to-laugh, prankster-boy personality.

From time to time, Carlos would try to challenge himself by enrolling in a computer programming course, but inevitably, he’d have to drop it. He just couldn’t keep up. He became a loner — a deeply misunderstood individual who’d rather isolate himself than try to interact only to be met with pity or outright judgment. Refractory epilepsy had stolen his intellect, his dignity, and his openness to building intimate relationships. It had stolen who he meant to be, everything he could have become if it hadn’t chosen him as its victim.

Nature just isn’t fair.

I remember running around a park in the Texas heat at the age of 4 with Carlos

When Carlos and I were children, he was my guardian angel. I remember running around a park in the Texas heat at the age of 4. I was wearing shorts, but no shirt. A pack of boys came over and started picking on me. Carlos looked them square in the eye and said, “I don’t see anything wrong with it.” And just like that, the boys left me alone. I knew then that as long as my big brother was around, I’d be safe.

Carlos and I were also bound by shared trauma: our father was physically abusive toward our mother and chaos and violence pervaded our household. We’d go to sleep to it; we’d wake up in the morning to it; it would jolt us out of our sleep at 2 or 3 a.m. We became as hyper-vigilant — as sensitive and attuned to danger — as comrades in battle trenches. Carlos and I unconsciously invented and spoke a private, worldless language. We could communicate nuanced messages to one another with no more than a glance or a quick hand gesture.

To this day, no one will ever understand my upbringing as wholly or completely as my brother did. But as time went on and we got older, our relationship changed. We grew farther and farther in opposite directions. When I started having boyfriends, Carlos, who had no friends and didn’t date, seethed with jealousy. And when I moved out at 17, he resented me for it — for abandoning him, but even more for my ability to live independently, which he would never have.

Grieving My Brother’s Death

When I found out that my brother had died, I wasn’t surprised, but I was shocked; I couldn’t believe it had really happened. I remember the day after: I drove around all day listening to “This Is The Worst Day of My Life” by System of A Down on repeat and crying non-stop — gut-wrenching sobs to the skies. I’d been trying for years to reconcile with my brother. And then — poof — he’d vanished. I’d never get another chance to connect with him, to recapture a fraction of the closeness we shared as children. This realization plunged me into the beginnings of a long, hard grief.

At the time, I wasn’t working: a blessing and a curse at once. On one hand, I had the time and space to immerse myself in the grieving process. If a song drove me to my knees, I’d let myself fall. If I needed to cry on the couch for hours, I would (and I did — every afternoon for two or three months straight). But eventually, I felt as though I was going insane with the burden of my grief, however necessary it was. I began to crave distraction — anything to occupy my time, to take my focus off the crushing, unbearable pain.

I couldn’t quit picturing Carlos sitting around looking at the cordless phone

in our mother’s kitchen, trying to will it, with the power of his stare, to ring

Credit: abc.net.au

Memories and regrets flashed before my eyes: intrusive thoughts robbing me of peace. My mind kept returning to one particular time when we were in our 20s. I told my brother that I’d call him after work one day, but when I got home, I was too tired to deal with his negativity and bitterness. My mother later gave me hell for skipping that call. “He stayed home all night waiting for it,” she said. I couldn’t quit picturing Carlos sitting around looking at the cordless phone in our mother’s kitchen, trying to will it, with the power of his stare, to ring. I couldn’t quit thinking about how silence must have filled the room, the idea that not even his little sister wanted to talk to him growing louder and louder in his mind with every passing hour. Why didn’t I just call him when I said I would? I kept thinking. What the hell was wrong with me?

I said, “I love you” to my brother all the time, but I don’t think he fully trusted it, believed it, or internalized it — he felt too unworthy to take that expression of love at face value. Carlos never knew how I thought about and fretted over him every day. I wish, more than anything, that he did.

My brother was an atheist, a nihilist, an austere, no-frills, no-nonsense kind of person — the kind of person who’d respond to an apology with, “Don’t be sorry, just don’t do it again.” It made sense to me when Carlos — who knew that his epilepsy would probably kill him one day — expressed, from an early age, that he didn’t want a funeral. But my mother and aunt arranged one for him anyway, which left me with an impossible decision: disregard my brother’s dying wishes by attending, or honor my brother by not attending, in turn disappointing and hurting my already-grieving family. Ultimately, on the day of the funeral, I chose to stay home — to grant him that last tiny bit of respect. It felt like the right thing to do, but it was still debilitating nonetheless.

Healing Through Shared Experience

For months after Carlos died, I couldn’t speak the words, “my brother is dead.” Instead, I’d say, “he’s gone.” One afternoon toward the end of the first phase of my deepest grief, my doctor suggested that I might need to go on blood pressure medication. I came home and faced myself in the bathroom mirror. I looked straight into my sallow, exhausted, beaten-up reflection — eyes red-ringed and shiny with tears — and in a steady, matter-of-fact voice said, “Your brother is dead. And he’s never coming back.” The out-loud admission was at once a source a relief and a source of demoralization. I didn’t want it to be real, but it was — it needed to be acknowledged. Nothing I or anyone else could do would ever change that fact.

But my mother and aunt arranged a funeral for Carlos anyway

Credit: marketwatch.com

Less than two years after my brother’s death, I was diagnosed with thyroid disease. I have no doubt that it developed as a result of my grief — that I’d run myself ragged with anguish, putting my body in a weakened, compromised state. At first, I thought, “It’s my turn to suffer. Epilepsy was my brother’s cross to bear; I guess now this is mine.” Over time, though, I began to look upon my illness not as some albatross or karmic punishment, but as a bridge that connects me to my brother. Just as we’ll be bound forever by a shared childhood trauma, we’ll be bound forever by the fact that I, like him, have to navigate my corporeal existence with a disease that sometimes makes me feel out-of-control in my body. As terrible and scary as this might sound — and as terrible and scary as it sometimes is — I’ve come to see it as a precious gift: one that I must treat with the utmost tenderness. I’ll never be able to mend the fractures in my relationship with Carlos, but I can nurture my thyroid, that I can take care of. And on days when I’m having a particularly bad flare-up — days when I’m struggling more than I ever imagined I would — I talk to my brother. “Help me, Carlos,” I whisper, like a prayer. And if I listen very, very closely — I can hear him answer.

I Lost My Brother To Refractory Epilepsy Long Before His Death

I Lost My Brother To Refractory Epilepsy Long Before His Death

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition