This is Tammy’s story as told to Jeanette Summers. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, aid them in their healing process. In this story, Tammy talks about her experience surrounding her older brother’s death after he contracted a bacterial infection that caused necrotizing fasciitis.

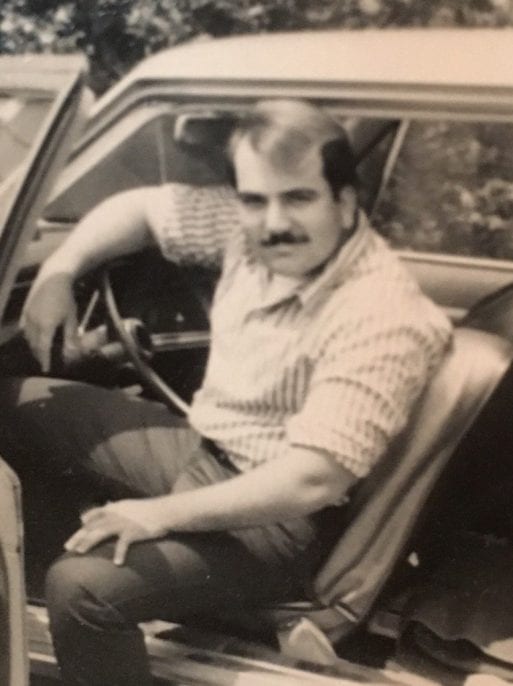

Louie loved his Chevy Biscayne. We had wonderful times together cruising the streets of South Hampton back in the day

Credit: Joe Vitale (@mrfire)

My older brother, Louie, passed away of a bacterial infection, which quickly consumed his whole body.

Louie was fourteen years older than I was — he was my half-brother, technically. Because he was so much older, he was more like a fun uncle than a sibling. I have so many years of beautiful memories: sleeping over at his place — a room rented for cheap in a dilapidated boarding house, which seemed magical simply because it was Louie’s — and riding shotgun on our regular drives to our grandparents’ house in South Hampton in Louie’s ‘66 Chevy Biscayne. It had bench seats and ladybug floor mats, and we rode with the windows rolled down and Indigo Girls blaring from the stereo.

The Louie I remember from my childhood was immaculately groomed and always in high spirits. But beneath his polished, sunny exterior, a secret smoldered: Louie was hiding a relationship with his close friend, M. — an older man with a wife and kids.

From that terrible day forward, Louie’s self-care — his diet, his personal hygiene, the cleanliness of his home — began to deteriorate.

The affair ended when M. died of a massive aneurysm. I was in college at the time. I remember Louie calling me on my Garfield phone. He was so hysterical that he didn’t even sound like himself. At first, I thought he was a prank caller. “M. is dead!” he shrieked, his voice warped and strange, its pitch a fever of raw, shocked grief, the rest of his words a jumble. From that terrible day forward, Louie’s self-care — his diet, his personal hygiene, the cleanliness of his home — began to deteriorate. Something inside him died, and it would never quite come back to life.

Eventually, Louie met another man: Roger. I simply didn’t feel that Louie and Roger were healthy together. They were miserably codependent. I could never spend any time with Louie one-on-one anymore. The way Louie neglected his health repulsed and saddened me, and Roger did nothing to help. And worst of all, Louie and Roger’s acute denial of reality and enabling behavior left me mortified. They’d continually bring my father, who was suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, marijuana to smoke. At one point, I told my family, “I can’t be around Louie’s toxic influence anymore.” This comment circled back to Louie and created an estrangement between us.

After his lover died, something in Louie died too. He stopped taking care of his appearance and his health.

He thought I’d become a know-it-all, and he stopped answering the phone when I’d call him. The happy, fun-loving “uncle” I’d adored growing up — the one who smelled of Bath and Body Works lotion, who was always humming Annie Lennox or Billie Holiday under his breath, who said, with a glint in his eye, that scrubbing a bathtub brought him “instant gratification” — was gone. In his place stood a man I barely recognized. For over a year, Louie and I didn’t talk at all.

Around the time that our father died — also, incidentally, around the time that I had my baby boy — Louie and I began to speak again. When he came to my son’s first birthday party, he was sour with body odor and his gums had gone purple-brown with gingivitis. I was deeply concerned, but I was so grateful that Louie was there celebrating with my family, I compartmentalized my horror. The last thing I wanted to do on this joyful occasion, this sweet reunion, was comment on my brother’s disgraceful hygiene.

Even though we’d mended our relationship, the residue from our estrangement lingered. We were never as close as we used to be.

Shortly after my son’s first birthday, my little family and I moved from our home on Long Island to Los Angeles. Right before Louie was to die — unbeknownst to me at the time — I’d road-tripped back to New York for a casual visit. I didn’t see Louie at all. Even though we’d mended our relationship, the residue from our estrangement lingered. We were never as close as we used to be.

On my drive back to LA, I got a frantic call from my mother: “Louie is in the hospital,” she said. “They’re about to amputate his leg!”

I didn’t understand. Louie wasn’t even sick, as far as I knew. What on Earth was going on? My mother explained to me that Louie had been diagnosed with a condition called necrotizing fasciitis: an aggressive, fast-moving flesh-eating bacteria that had crawled beneath Louie’s skin and was spreading through his body. Its probable cause: poor hygiene.

Louie’s only response: “I’m goin’, sweetie! I’m goin’!” He knew. He just knew.

I did get to speak to Louie on the phone one last time. “Louie, what’s happening?” I said. “I’m so sorry I didn’t get to see you while I was in New York,” I said. “Listen to whatever the doctors are telling you,” I said. “It’s going to be okay,” I said. Louie’s only response: “I’m goin’, sweetie! I’m goin’!” He knew. He just knew.

I spoke to Louie for the last time on the way to California. He knew he was dying but I still was in shock.

My husband and I had no choice but to keep driving west. We were farther from New York than we were from California, and it didn’t make sense to turn around. As I sat for hours at a time in the front seat — grappling with the magnitude of my brother’s condition — I kept thinking of all those times I’d ridden shotgun in his Biscayne. I couldn’t get Lucie Blue Tremblay’s “The Water Is Wide” — a song Louie and I would always listen to together — out of my head: “The water is wide / I can’t cross cover / And neither have I wings to fly / Give me a boat / That can carry two / And both shall row / My love and I.”

I vividly remember seeing my baby son standing in front of a fireplace at a Colorado ski resort we stayed at for one night en route back to California. He was wearing a baggy plaid flannel, which, for some reason, thrust me into a memory: an oversized patchwork jacket that Louie, who always adored warm, cozy things, had gifted me when I was 15. I loved that jacket, but I have absolutely no idea what happened to it. Did it get thrown away or sold for $5 at a tag sale? Or is it sitting in a musty secondhand bin at a thrift store somewhere on Long Island? That rush of nostalgia — that longing for a lost symbol of the closeness Louie and I once shared — was accompanied by a deep, inexplicable inner knowing: Indeed, my brother was going to die.

I vividly remembered the jacket Louie had gifted me, and the memory thrust me into the knowledge that my brother was going to die.

Credit: Jenny Bruso/outsideonline.com

My husband, my son and I were in Kansas when my mother called to tell me about the amputation. By the time we got to Utah, my brother was dead. As soon as we reached Los Angeles, we hopped right on a flight back to New York.

On the day of the service, Louie’s body — turned to soot in a brass urn — sat at the front of my family’s church. It was strange to me that Louie hadn’t been embalmed. I wanted to see him all dressed up and clean-shaven one last time — but I never got that. I did get to meet several of his work friends, though. I’d never heard any of their names, but they knew all about me, albeit on a surface level: I was Louie’s little sister, Tammy, who he loved so much and talked about all the time — the one with the beautiful new baby boy — the one they recognized from pictures. I felt that Louie had condensed me, as a character, into something neat and simple — something he could share with people. And in a way, that broke my heart.

I guess he assumed, just like I did, that he’d have more time. That we’d have more time.

I always hoped that my relationship with my brother could be restored to what it once was. I always wanted to reconcile with Louie, to truly be close with him, like I used to be. I know that Louie didn’t expect to die. The last time I ever saw him alive, he’d just gotten a haircut for the first time in months and he’d just had his car inspected and filled his tank up with gas. I guess he assumed, just like I did, that he’d have more time. That we’d have more time. But we didn’t.

I wish I would’ve explicitly told my brother that he shaped me into the person I am: my love of music, my loving spirit, my lust for life. I can only hope that somehow, Louie knew.

My Brother’s Unexpected Death from Necrotizing Fasciitis

My Brother’s Unexpected Death from Necrotizing Fasciitis

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition