Manena and Dan shortly before he was diagnosed with prostate cancer

This is the story of Manena and her husband, Dan, as told to Jeanette Summers. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this post, Manena talks about the fact that though her husband died from cancer, she lost him to morphine first. She also shares memories of Dan’s life and work.

As a death midwife — or, as I prefer to say, an end-of-life nanny — I’d had plenty of exposure to death. As a bodyworker, my husband, Dan, bore witness to literally thousands of patients’ physical agony and discomfort. In spite of our professions — our ongoing proximity to pain and grief — nothing could fully prepare us for my husband’s cancer diagnosis and the effects of the morphine he eventually needed for pain.

Dan and I had been together for 15 years. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in May and died only a few short months later. At the time of his diagnosis, we were in the process of moving from Oregon to Santa Rosa, California, and living in a small trailer. Dan was in denial for a long time. He turned a blind eye to his incapacitating backaches and vomiting episodes until they increased in frequency and severity, and eventually became impossible to ignore. Finally — when he was barely able to move — I convinced him to go to a hospital ER. The doctor there delivered unthinkable news: Dan was going to die. His cancer had progressed and metastasized to the point where chemo wouldn’t help much. It would only destroy Dan’s precious and limited remaining days on Earth. And so, he decided to forego it.

Close friends generously offered us their house in Sebastopol to live in. I called it compassionate care housing. We lived out Dan’s final months there. I could barely leave the house, and I didn’t want to. Over the course of these months, I found myself surrounded, cradled, and uplifted by my tribe: an unbelievably supportive network of friends. They came to visit, brought me potluck meals and ice cream, sat and watched movies with me. Just as Dan’s spirit had begun to transition out of his body — I could sense him waning a little more each day — my grief started to take hold months before he sipped in his last breath. My husband hadn’t exactly disappeared yet, but he was actively disappearing — bit by bit — before my very eyes. Throughout this time, my friends were my guardian angels. They offered me tremendous solace and comfort during one of the saddest and most vulnerable periods of my life.

We tried to treat Dan with medical marijuana, but eventually, the quantity required for effective pain management made him gravely sick. So we resorted to morphine, which transformed him into a different person — not the kind, patient Dan I’d always known. The anger and frustration I felt at that time consumed me. Dan had invented a tendon-centered bodywork technique that he named Tandano, which translates — from Italian to English — to “tune the strings of a stringed instrument.” How cruelly ironic that a man who’d helped so many people manage their chronic pain was suffering in a way that couldn’t be lessened by anything other than an opioid that made him unrecognizable! Dan was going out of tune so quickly, and no one — including me — could stop it.

During the last month of Dan’s life, he didn’t make a sound; he couldn’t speak. Dan was filled with a silent, impotent, almost panic-stricken rage. He was no longer capable of standing, but he kept hoisting his body out of bed, falling to the floor, and trying to crawl around the house on his hands and knees — maybe a desperate attempt to stay in motion, to run from the inevitable fate that was stalking him, picking up speed, coming closer and closer every hour. My husband was dying from cancer, but morphine was taking him away from me first. For Dan’s safety, I moved his mattress onto the floor.

I vividly remember lying next to him one day; at this point, I could hardly connect with my husband at all. But in a startling, momentary glimmer of lucidity, he reached over and kissed the coffee-colored birthmark on my hand. Dan — so good with his hands, a baker by trade before he became a body-worker — always called this birthmark my “sugar spot.” It was the place where the ingredients I was made of didn’t sit quite right — where my maker didn’t properly mix the sugar into the dough of my skin. This left me with with a brown, granulated clump of sweetness: my loveliest flaw, and Dan’s favorite part of my body. I have no doubt that this kiss was my husband’s way of saying goodbye wordlessly.

In the days preceding Dan’s death, I finally had him transferred to a local hospital. Because of my line of work, I’ve been with a lot of people during their final moments. I’d like to say that I always feel something profound when a patient dies; in truth, though, I don’t. But when Dan died — on a night when a full moon hung low and white in the sky — I could feel a million stars releasing from his body all at once — a succession of tiny lights bursting, surging out, scattering, flying up and away into the wild September night. He was free of suffering and the effects of the morphine that had gripped him.

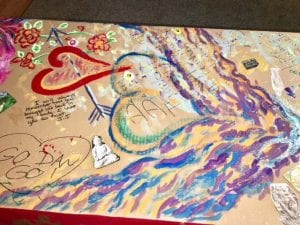

I’m familiar with home funerals; I believe they give loved ones more time to say goodbye in a comfortable, intimate setting. I wanted to do this for Dan, for myself, and for our friends. And so, I took a cardboard box with me to the hospital and brought his body home in it. My friends and I dressed Dan in his favorite Hawaiian shirt and lay his body on an old massage table for the ceremony. After, we moved his body back into the cardboard box — his casket — and painted and decorated it. We held a three-day vigil, throughout which we kept Dan’s body on dry ice. When it was time to drive him to Santa Rosa Memorial for cremation, I sang him his favorite song — “Love Is A Many Splendored Thing” by Andy Williams — the whole way.

I bought a small Pier 1 cremation container, which looked like a mini washing machine and put my favorite picture of Dan in its window. It took extra-long for my husband’s body to turn to ash; in spite of muscular atrophy from months of bed rest, Dan’s bones remained denser than most people’s. He was impossibly strong, even after death.

I’d planned to drive along the coast from California to Oregon to give my daughter, who’d just had her first baby, a helping hand. To say that I couldn’t wait to meet my grandchild was a vast understatement. This would be a celebration of new life — a perfect salve for the wound of my loss. On my way, I would stop to camp, all by myself, in the California Redwood Forest. But shortly before I set out on my journey, I stumbled upon a white rose bush in an abandoned garden close to the hospital where Dan died. It struck me that my husband — who had such gentle, nurturing, intuitive hands, and always loved to garden — would have done a beautiful job tending to this bush. And so, I went home, grabbed that mini-washing machine, drove it back to the garden, and scattered his ashes beneath it. I returned to this exact spot a year later. Most of the wild plants and flowers looked withered and neglected. But Dan’s rosebush was glorious — lush and so very alive. Thriving all on its own.

My Husband Died From Cancer, But I Lost Him to Morphine First

My Husband Died From Cancer, But I Lost Him to Morphine First

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States