Her bowling ball was all I had to remind me of her, so why did I leave it in the desert?

This is the story of Cara as written by her. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this post, Cara writes about some of what she knows — and doesn’t know — about her mother, Jo Ann, who died when Cara was 7 years old.

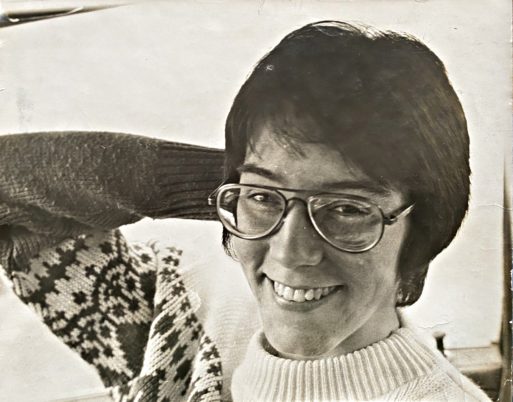

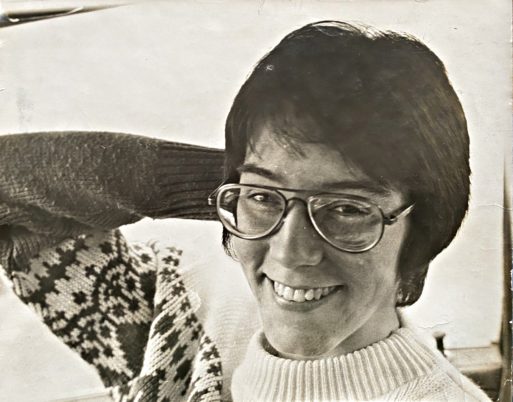

My mother was shy and didn’t like having her picture taken, but I’m glad she posed for this one. Jo Ann had a beautiful smile.

My mother died when I was 7. I didn’t know she killed herself until much later, but that’s another story. This wasn’t her first attempt, and she didn’t want to die. She just didn’t want it to hurt anymore. That’s all any of us wants, when you get down to it.

I grew up not knowing much about her. My dad told stories about things they did together, but he didn’t tell me about her personality, her sense of humor, her reasons for loving her favorite things. I haven’t asked him why he didn’t (yet). Probably some version of “it hurt too much.”

But I always knew a few details. My mother was a nurse, and a good one. She loved horses and loved to draw. She liked to eat the pith on oranges. When my dad and his brother set up target practice in the backyard, she was a remarkably good shot even her first time firing a rifle.

Her custom bowling ball taught me I have the same hands she did … My two fingers and thumb fit the 12 pounds of marbled plastic like they were mine.

But, for years I didn’t know she loved to sing, or that she was deeply uncomfortable having her picture taken. I didn’t know that she was shorter than me; she was my sister’s height, actually. I had no idea she was funny — or a thousand other things.

Her custom bowling ball taught me I have the same hands she did. I started borrowing it while dating my high school boyfriend; sometimes we went bowling with his friends, who became my friends. My two fingers and thumb fit the twelve pounds of marbled plastic like they were mine.

Before I was born, my parents bowled enough that they bought custom bowling balls, their initials engraved near the holes. His was blue and hers was brown, like their eyes. A young married couple in the late 1970s, spending Saturday night at the lanes — my dad told this story occasionally. Then they had kids, and at some point the bowling balls went in the closet, and life went on — until my mother died, and it didn’t anymore.

My parents loved each other dearly and looked for themselves in each other. They got married when my dad was 24 and my mom was 19.

I don’t bowl; I’m not a bowler. Or rather, I have bowled, and I’m a shitty bowler who can’t break a hundred. I tolerate bowling when my friends want to go. But even as a casual bowler, I understood a perfectly fitting bowling ball is something more meaningful than just a novelty. My mother’s bowling ball fit my hand so well that even though I don’t bowl, after college I got my dad’s permission to drag it with me to the other side of Ohio, just in case my friends there went bowling.

But I didn’t ask my dad if I could take the bowling ball 1,500 miles further away to grad school in New Mexico. He hadn’t said I couldn’t, so I didn’t ask. Anyway, it seemed foolish to put it back in the closet in our basement rec room.

But in New Mexico, none of my friends bowled, so for three years the ball sat in my own closet. When I graduated and got the hell out of the desert (though I love the desert — but that’s another story), I left my mother’s bowling ball behind. My friend Carrie inherited it when she moved into my adobe apartment, along with the free couch I’d also dragged from Ohio, my sagging bed, and all my jewel-cased CDs.

I shipped my boxes of books and my wooden trunk full of family stories to my next city, but beyond that I only brought what fit in my car. The bowling ball was twelve pounds of dead weight, and it didn’t make the cut. I told Carrie that anything in the apartment she didn’t want could go to the thrift store. I figure that’s where the bowling ball ended up, but maybe Carrie just threw it away. I’ve never asked her (yet).

My mother died and became algebra I did with variables. She equals me minus my dad plus X, times Y. Knowing my mother is solving for X. I don’t know if Y is a whole number or a fraction.

A few years after grad school, I started trying seriously to write about my mother, for the first time ever. It was confounding to realize I couldn’t. I was trying to write a short story — fiction, just making things up — with a main character based on her, but I couldn’t imagine what that character would do or say. She was silent, inert. Her character didn’t do anything. When things happened to her, she didn’t react.

But I kept trying to write about that character. I shifted to poetry (on the advice of a poet, go figure), and the poems I wrote about her turned into math. My mother died and became algebra I did with variables. She equals me minus my dad plus X, times Y. Knowing my mother is solving for X. I don’t know if Y is a whole number or a fraction.

Sometimes, during those years of writing, I thought about how I hadn’t told my dad I left his beloved wife’s bowling ball in the desert. Who does a bowling ball belong to, when the woman it was custom-made for has died? Right or wrong (or both), I didn’t see the ball as my dad’s. But I always made sure never to tell him it was gone. As a family, we’re a little too good at not telling.

My dad never said the bowling ball mattered to him — not in words. Words are my thing; they’re how I understand best. But words ain’t my dad’s thing. He says things in other ways (I’m learning to understand this better now), like keeping his wife’s bowling ball next to his in the closet for years and years.

But my dad tries to use words. He does his best. Every now and then, he says he thinks about my mother every day. He’s said this my whole life. He doesn’t say more, but those few words ain’t nothing. My poet friend would tell me to think of it like a poem: a few words holding so much meaning.

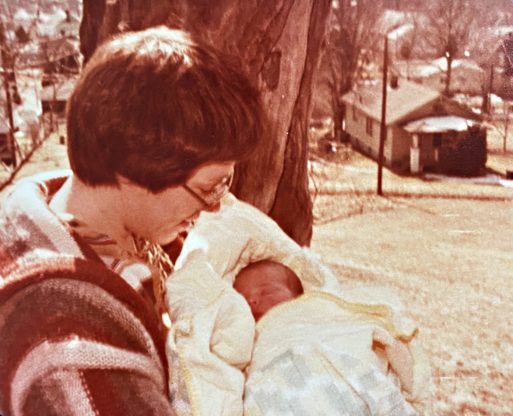

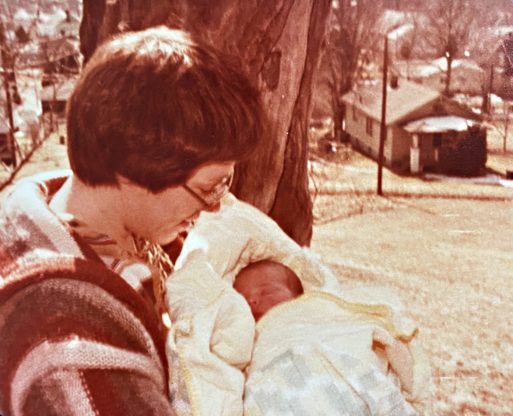

Jo Ann was so happy to be a mom. I was her first child, and she was excited to help me learn who I was. But my mother died before I knew who she was.

I didn’t start thinking about my mother every day until my 30s because I had no idea who she was or what I was missing. (How sad would it make my dad to know that?) I didn’t start using her name, Jo Ann, with any regularity until recently. I only started calling her my mom this year.

I was only 7 when Jo Ann died, but I do remember her, a little, in stills and two-second clips. Trailing her skirt down the aisle at the art supplies store. Crying at her newly permed hair. Wiping her kiss off my face (I don’t remember the kiss itself) and her saying, “But the love is still there.” But I don’t remember her voice.

I remember when I was 3 or 4 and my sister was just born: I walked in on my mom naked on the toilet. She lifted a breast and squirted milk at me, and I fled. This is hilarious. But until this year, it never occurred to me that she probably thought it was hilarious too. My dad never told me my mom was funny. He just didn’t have the words.

I think more and more about what Jo Ann might have shown me, if she’d been able to survive. Who she is. Who I am … I have so many questions now.

I’m funny too. Now I wonder all the time how much I’m like my mom. It’s a deep comfort to look at someone else and see yourself — my parents did that for each other. That’s why my dad loves Jo Ann so much, still. These days I think more and more about what Jo Ann might have shown me, if she’d been able to survive. Who she is. Who I am. How to talk and listen, in words and other ways.

My mother died over 30 years ago, and now, finally, I think about her every day.

I have so many questions now. About everything, anything. Even little things, like — did Jo Ann think it was funny that her husband’s bowling ball was blue? I have never, ever heard my dad say fart or boobs — it ain’t his thing — but did Jo Ann think it was hilarious to give him shit about his big blue ball?

It’s been over a decade since I left my mother’s bowling ball in the desert. I remember packing my car in the dirt lot behind my little adobe apartment, deciding what would make the cut. I remember looking at that bowling ball for a long time. I knew if I left it behind, I’d never again put my fingers into a bowling ball that fit my hand perfectly. But I was okay with that. I don’t go bowling.

I was too young to remember washing dishes with my mother as a toddler. I remember our kitchen growing up, the sink and stove, and even the plastic cups in this picture. But I wish I remembered more of her.

But I didn’t understand that putting my fingers in those holes was as close as I’ll ever get to holding my mom’s hand. Now I know. (If I put my hand in my father’s, is the fit familiar to him? I haven’t asked him yet. But I can.)

But — it’s also a bowling ball. Twelve pounds of dead weight. A metaphor in real life. And I didn’t want to drag it another 1,500 miles just to shove it in another closet.

Since I left New Mexico, the bowling ball’s absence has ballooned. Now it’s bigger than the ball itself ever could be. Losing it holds so much meaning. These days I want as much of Jo Ann as I can get, and I wish I could put my fingers in that bowling ball one more time. My mom is a hole I want to fit perfectly into — and I don’t, but I love every difference between us too. And while my grief at her absence grows every day, it’s not heavy. It doesn’t drag me. My mother died, and it hurts. But unlike a bowling ball, this pain is weightless.

How happy would it make my dad to know I love Jo Ann more and more every day?

My mother’s bowling ball. I don’t want it back. If it were here, it would be 12 pounds of plastic in the closet of a shitty bowler. But now it’s a story I tell. I’m a good storyteller. I love stories.

But I still don’t bowl. Ain’t my thing.

Rutgers Health Study May Improve End-of-Life Care: Medicare data analysis finds that people typically follow one of nine paths

Rutgers Health Study May Improve End-of-Life Care: Medicare data analysis finds that people typically follow one of nine paths

Mary Oliver’s “Heavy” Speaks to the Weight of Grief: The poet eloquently conveys the dizzying effect of loss

Mary Oliver’s “Heavy” Speaks to the Weight of Grief: The poet eloquently conveys the dizzying effect of loss

Did Our Ancestors Leave Behind a Map of the Afterlife?: Archaeological discoveries suggest link between ancient monuments and burial sites

Did Our Ancestors Leave Behind a Map of the Afterlife?: Archaeological discoveries suggest link between ancient monuments and burial sites

Happy Hanukkah from SevenPonds

Happy Hanukkah from SevenPonds “Let winter come and live fully inside you, so that you can retrace the loving path of heartbreak that brought you here.”

“Let winter come and live fully inside you, so that you can retrace the loving path of heartbreak that brought you here.”

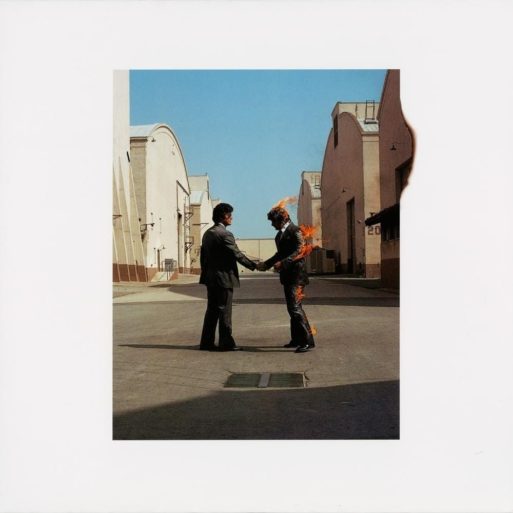

Pink Floyd’s Tribute Song to Syd Barrett’s Life “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” Still Shines

Pink Floyd’s Tribute Song to Syd Barrett’s Life “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” Still Shines There is no better song to remember a loved one by than the masterpiece send-off that is Pink Floyd’s “Shine on You Crazy Diamond.” The nine-part composition was written by Roger Waters, Richard Wright and David Gilmour and appears on the 1975 album “Wish You Were Here,” which also features a song of the same name. Both “

There is no better song to remember a loved one by than the masterpiece send-off that is Pink Floyd’s “Shine on You Crazy Diamond.” The nine-part composition was written by Roger Waters, Richard Wright and David Gilmour and appears on the 1975 album “Wish You Were Here,” which also features a song of the same name. Both “

My Mother Died When I Was Seven

My Mother Died When I Was Seven

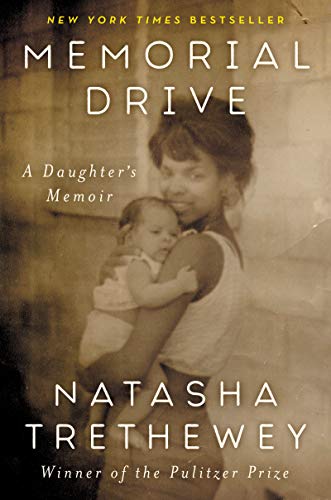

“Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Natasha Trethewey

“Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Natasha Trethewey The terrain of grief and loss is challenging enough on its own. But when a loved one’s death is shrouded in trauma, these emotional regions can remain long unexplored, as though obscured by thick fog. In “Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir,”

The terrain of grief and loss is challenging enough on its own. But when a loved one’s death is shrouded in trauma, these emotional regions can remain long unexplored, as though obscured by thick fog. In “Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir,”