Pathologists’ Assistant and author Bruce Koepp

After earning a Ph.D. in forensic pathology from Columbia Pacific University in California, Bruce Koepp spent the next 43 years working as a pathologists’ assistant, an occupation that was created in 1969 to address a pathologist shortage. He started in hospital pathology labs, then spent the bulk of his career working as an employee for private companies providing autopsy services. Now retired from PA work, he estimates that he has performed more than 1,800 autopsies during his career.

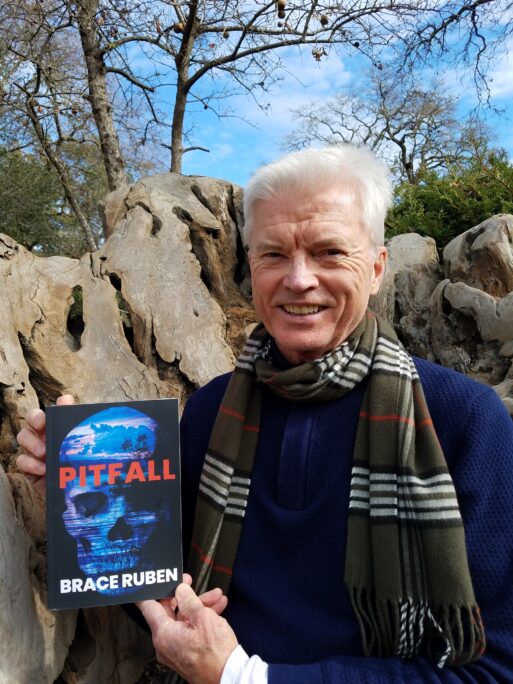

Koepp continues to participate in the field through peer review of articles for professional journals, as well as lecturing and teaching. He has used his experience to launch a second career as a novelist. Writing under the pen name Brace Ruben, his latest novel is “Pitfall,” a thriller about a forensic pathologist drawn into the 40-year-old mystery of a friend’s disappearance. Koepp agreed to speak to SevenPonds about the role of a pathologists’ assistant, the autopsy process and what to expect when a coroner requires an autopsy of a loved one.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is a pathologists’ assistant?

A pathologists’ assistant is a someone who has professional training in anatomy and disease process that works in the pathology department under the pathologist. The pathology assistant is responsible for the dissection and anatomy (describing the physical structure and features) of tissues that are delivered to the laboratory. And that includes the autopsy service. The pathologist generally is the person who provides the microscopic examination of tissue samples and renders the diagnosis. So they compile their anatomic and microscopic findings and make a diagnosis in that direction. Most pathologists’ assistants have a master’s degree.

What drew you to the field?

In college I was always drawn to anatomy and dissection. Biology. But specifically, disease-related human anatomy, and that’s the direction I went.

Every death requires a death certificate and the person who issues that is either the county medical examiner, who is usually operating in a larger city, or the more common county coroner. While the medical examiner is a medical doctor — typically a pathologist — a county coroner doesn’t have to be a doctor, correct?

Right. When you get into smaller states and smaller counties, the coroner is usually the sheriff, and sometimes it could even be the funeral director. And what they’re responsible for is just to document the death and then converse with a professional pathologist if need be on whether to pursue an autopsy or not.

Take us through the process of when the coroner shows up after a death at home. What kind of questions should the family expect at the start?

The coroner will start by asking when they last saw the deceased alive, followed by questions about medications and questions about health. There’s a kind of checklist that they will follow. And then, of course, they’ll look through the death site. Did the person die in a bed or did they find the person on the floor in the kitchen, etc.?

We have a mnemonic, which is called NASH. It stands for Natural Accident Suicide or Homicide. So if they find the deceased in their home, questions will arise whether one of those mnemonics is indicated and if it’s a natural death.

Sometimes the coroner will not do an autopsy on a natural death based on clinical findings or based on the medical findings of the person or based on the medical records. But anything beyond that — an accident, suicide or homicide — automatically requires the coroner system throughout the country to order an autopsy.

So those are all parameters that need to be evaluated. And if they feel that there aren’t any areas of suspicion, it’s a natural-looking death and everybody agrees with that, they might waive the autopsy and just issue the death certificate.

Can a family member ask for a business card for future follow-up?

Yes. All county employees should have their own business cards. And employees of independent companies have cards too.

What should relatives expect when the body is taken into the county system for an autopsy?

Depending on where the death happens, it will be the medical examiner’s or coroner’s office with several refrigeration units. Then they’ll be assessed, assigned a number and a name tag and scheduled for an autopsy. It could be the same day. It could be the next day. Could be maybe the day after, depending on the workload. The family should expect to receive the body 48 to 72 hours after it’s removed.

And then they can make the funeral arrangements through a funeral home. Sometimes in smaller states or rural counties and rural areas, the coroner’s facility is actually a funeral home. And so the body would be sent right to the funeral home, and it’ll be held there. And the postmortem examination will be performed right there at the funeral home. Much of my work was done in funeral homes around the country.

Typically, how do the families react when they’re told that an autopsy is required?

It’s all over the place. One of the issues that we encountered countless times is that they’re in a grieving process and anger is first and the grieving is last. And so they’re frustrated. They’re angry about finding their loved one dead. They talked the day before. They [the deceased] were happy. They were smiling and joking. And now they’re dead. Someone came in and something happened, something very suspicious, because this should not happen. And it’s hard to convey to a person who’s grieving with anger that it’s probably not that case.

So, we’ll explain step by step how the process works and that it will identify the issues anatomically that may have caused the death. And then they’re okay with it. So of course there are cultures that don’t want autopsies.

Can a family refuse an autopsy?

Yes, it’s their right to say no. Unless the coroner’s office or the medical examiner calls it a suspicious death, then it automatically becomes the responsibility of the of the coroner.

Removal of the body for an autopsy requires a signature by a family member. So who qualifies as a family member?

Next of kin has to be a spouse or a parent. Then it goes to brother or sister, followed by aunts and uncles. If there’s nobody they can find to be immediately responsible, then they declare that person a John Doe or a Jane Doe.

Can a family member request a copy of the report and the toxicology report?

Yes, the reports are issued only to the immediate next of kin — the person who signed the authorization for the autopsy. What they do with it is up to them. But only that person who gave their signature gets the copy, and it’s theirs to have. It can be a postmortem examination. Sometimes an autopsy can be a toxicology. A tissue sample can be considered an autopsy, too. And that happens a lot in natural death causes. When medical examiners or coroner’s officers show up at the home site, the first thing they do will be to draw blood. And a lot of findings can be just through a blood sample.

When the coroner says we need an autopsy, who pays for it?

If the coroner’s office is going to have the autopsy, there’s no charge. That’s part of the county service.

In some cases, though, family members may want to know why their loved one died, particularly if it was sudden and unexpected. Can they request an autopsy?

Yes. That can be done. There are a couple ways to do this. If it’s a hospital death and the pathology department does not do autopsies — and that is becoming more common if you’re not a teaching hospital — it’s up to the next of kin to find somebody to do the autopsy. And that’s where the independent services come in. If it’s a teaching hospital where you have interns and residents, they’re probably going to have a fairly large autopsy suite, and they might have several autopsy tables. And that’s where the medical interns learn.

Otherwise, the only resort that they have is to find an independent service. And there are several around the country. Most hospitals that don’t offer autopsies will have a reference to a service.

What does it cost?

If it’s a total autopsy — they call it a “complete” — it can go as high as maybe $5,000 or $6,000 or $7,000. If it’s organ specific—say the deceased had a bad heart and the family just wants to find out what happened to their heart, that’s much less. And there are autopsies for litigation. Attorneys will hire pathologists to study the tissues removed at the autopsy.

What can the family do to ensure they get the answers they want?

They should express what they’re expecting to find. Are they expecting pills in the stomach, and that toxicology is going to come back showing there were drugs? Are they expecting to find a heart attack? Or cancer? Do they want the cancer mapped throughout the body? Those are questions that need to be answered verbally before an autopsy. And this needs to be clarified right up front, that the autopsy only identifies the physical and microscopic findings.

We go through the dissection of the anatomy, discuss the pathology of the organs, and the microscopic results follow. And that’s all they’re going to get. They’re not going to get any opinions. It’s all going to be strictly detailed organ by organ or organ specific or whatever they wanted to have.

And there’s no bias. They can’t come back and say, well, you didn’t do this the way we wanted it done. And there are cases like that. But I think generally overall people aren’t in the litigious mode when it comes to an autopsy. They just want to have an answer.

Does an autopsy prevent an open casket viewing?

It does not. There’s no disfigurement to the body. You’ll see the stitch marks if you have a body without clothes, but generally the face is unaltered. Even in cases where the brain was removed, you can’t even tell.

So for some people an autopsy my help bring them closure.

This is a [final step] that most times is not addressed. And this is one way that a pathologists’ assistant can help with the grieving process by giving actual answers.

Along those lines, give us an example of a time when you personally saw the positive impact your work had on a surviving family member.

I had an autopsy at a little county funeral home, and I walked in and there was a man sitting on a bench outside the prep room. And he was an elderly man, and he was looking down. So I didn’t pay any attention to him as I walked in and introduced myself to the funeral director and embalmers. And they said this is so and so and you’re going to do an autopsy on his wife. I said, oh boy, I don’t want him to walk in, you know, what do I do? And the funeral director said that the husband just wanted to be there for her at this moment. So afterward I came outside and he was waiting there. And he was so thankful that someone cared to spend time with him and give him answers and go through his grieving process. He hugged me. He started to cry. It was very it was very touching. And I’ve always carried that memory. And that happened maybe 20 years ago. But that hit home.

So I assume the only impact on the funeral is that it might affect the schedule because the family has to wait for the return of the body.

Yes. Theoretically, if they’re going to have a viewing, it slows it down. But often the autopsies are done in the funeral home. Then they don’t have to transport the body. It’s already there cleaned up and on the table. They just begin the embalming process. The cosmetics, the dressing. The casket selections are already done, I’m sure. So, it doesn’t change the prepping portion of it. It’s probably just the scheduling of the funeral.

What percentage of your autopsies were done in a funeral home versus a medical facility?

At the end [of my career], when fewer hospitals were doing or performing autopsies or more hospitals didn’t have a standard morgue. I would say maybe 70%, because I was doing research autopsies, too, for mesothelioma or Alzheimer’s studies. All those bodies would be going to the funeral home. So very seldom did I end up at the coroner’s office for cases.

So what advice would you give to somebody who is considering becoming a pathologists’ assistant?

It’s always been a very specific field [the American Association of Pathologists’ Assistants has 1600 fellow members]. The turnover rate is not drastic. But you have a generation now of people who want to be in the medical laboratory situation and pathology is a very intriguing side of it. You still have to put your gloves on and dissect the tissue. Sometimes you might have to do a dissection of a leg or a jaw. It’s very interesting to learn the process of this.

You need to have an extensive knowledge of anatomy and surgical dissection that pathologists rely on you to do for them or to do for the department. … You have to be prepared to handle a workload of maybe 20 or 30 cases a day five days a week and be trustworthy. … I see a lot of excellent candidates now.

So now that you have time for other things, you’ve launched a second career as a novelist. How did that get started?

I’ve always enjoyed reading, and I started writing on weekends, which led to short stories and poems and then novels. My work has some forensics in it, you know — fact in the fiction, not the other way around. So, yeah, I’m having fun with that. I have two novels published and two being edited right now.

Well, congratulations on your new venture. And thanks for spending time with us.

Bruce Koepp Removes the Mystery Around Autopsies

Bruce Koepp Removes the Mystery Around Autopsies

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”