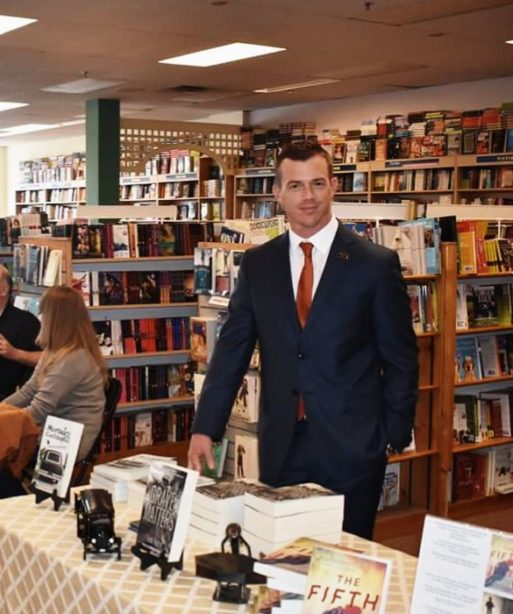

Todd Harra at a book signing for “Last Rites: The Evolution of the American Funeral”

Photo credit: Todd Harra

A fourth-generation undertaker who lives in Wilmington, Delaware, Todd Harra is an author who enjoys writing about his profession in his spare time. Having collaborated with Kenneth McKenzie to create “Mortuary Confidential: Undertakers Spill the Dirt” and “Over Our Dead Bodies: Undertakers Lift the Lid,” Todd’s latest work, “Last Rites: The Evolution of the American Funeral,” explores how certain funerary traditions came to be. SevenPonds recently sat down with Todd to learn more about the origins of certain American death rituals.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity

You begin this book with Lincoln’s assassination and funeral. Would you mind telling our readers why that was such a pivotal moment in American funerary history?

Lincoln’s funeral, in my opinion, set the template for the modern American funeral for a number of reasons. Prior to Lincoln’s funeral, the early American colonial funerals were very kind of quiet, austere events where the family would gather in the home and wash the remains, and the community would come in and hold a wake for the person.

The local cabinetmaker would make a custom-built coffin, and then the person would be taken out to the churchyard, or maybe a piece of family land, and buried. And initially, no prayers were said at the gravesite. No funeral sermon was held. The community would gather for a repast, and that would be the extent of the American funeral.

As things progressed, Americans started having funeral services. These were held during church services, and they were typically in the weeks following the burial. And then prayers, eulogies, and elegies were offered at the graveside.

The American funeral continued to evolve from the first settlement at Jamestown, but then after Lincoln’s assassination, things changed rapidly. And I’m not saying all these things were created because of Lincoln’s funeral. All these elements were there. But to use a kind of a chemistry term, Lincoln’s funeral was the activation energy needed to create this big change.

One of these changes was embalming, which began with the Civil War when soldiers bodies needed to be taken long distances to be buried at home. Lincoln was embalmed for the same reasons. I think he traveled 1,662 miles during his funeral journey. A total of 8,800 Americans cast their eyes upon Lincoln, and some of them saw him two weeks after his assassination. Now, up until this point, Americans were used to the dead and dying in their homes; they knew what happened when somebody died: nature took its course, and people started to decompose.

And here’s the President two weeks after death, and he looks great. It was almost like a miracle that happened: embalming was this new sanitary science. And the prevailing thought with people was, well, if it’s good enough for the President, then it’s good enough for me. All of a sudden, Americans began to embrace this new practice after the Lincoln funeral.

What else changed with Lincoln’s funeral?

One of the other things was the prestige of the coffin or casket. So, as I said prior to this, the local cabinetmaker would knock together a very simplistic coffin. Sometimes, if it was a family of means, they could pay for the coffin, the handles, the tax, and the badges and emblems that could be affixed to ornament the coffin. But Lincoln’s coffin cost $500. Adjusted for today’s prices, that’s $25,000. And this grand coffin was paraded around in each city that the funeral train stopped at on these custom-built hearses.

Millions of people saw the President’s grand coffin go by in these processions. I would say the symbolism and the use of the coffin was elevated due to Lincoln’s funeral.

“Last Rites: The Evolution of the American Funeral” by Todd Harra

What other details changed?

Floral tributes were, I don’t want to say rare, but they weren’t used as frequently prior to the Victorian era. And Lincoln’s funeral definitely kind of set this off. Each city tried to outdo themselves. All these fraternal and social organizations would want to offer something, so they would offer a floral tribute. Floral tributes in the American funeral really gained prominence after Lincoln’s funeral.

And then the other thing is the hearse. Prior to the Civil War, a hearse was something of, honestly, an extravagance, really. These were people in a new world scratching out a living. And a vehicle that was solely used for the movement of the dead was almost kind of a frivolous thing; the colonials would use buckboard wagons if they needed to. But typically the caskets were carried by hand because they were going to the churchyard, which was close to the home or the family land.

During the Victorian era, pre-Civil War and post-Civil War, Americans began burying their dead in what are called “rural cemeteries,” which were miles from the city center. So all of a sudden, a specialized vehicle, the hearse, kind of emerged in America. Now, these were used in Great Britain at the time, certainly, but they started to emerge in America during the Civil War.

Then the last thing to evolve was mourning garb. When Queen Victoria’s husband died, she wore all black, so Americans began copying this. During the Civil War, when family members were dying, the survivors put on all black to show that they lost a family member, so families could have solidarity with each other.

When her husband was assassinated, Mary Todd Lincoln put on all black mourning garb, and she wore it the rest of her days. We see mourning garb kind of take off in the post-Civil War Victorian era as a piece of the mourning ritual.

All of these kind of disparate pieces that the Lincoln funeral brought together really created the template for the modern American funeral.

You give a comprehensive history of the origins of the American funerary rites and traditions. Of all funerary eras, what is your favorite anecdote or detail about pre-modern funerals?

One of the most interesting things, and the thing that I think that readers are most fascinated about, is kind of this period in time when we have these men called “resurrectionists” who were emptying America’s cemeteries for anatomical dissection material.

This was a period that goes all the way back to the mid-18th century, and you see it happening until the turn of the 20th century.

There was a big trial in 1902-1903, I think, when Rufus Cantrell, the self-proclaimed “king of all grave robbers” was put on trial. Cantrell bragged that he had pilfered the graves of 1,200 people. He was making $50 per set of remains that he would bring back to the doctors, which back then, was a lot of money.

I would say the most interesting thing I learned was how John Scott Harrison’s body was snatched. Of course, he was the son of William Henry Harrison and the father of Benjamin Harrison, so he was connected to a very powerful political family. Scott himself was a congressman, and it’s almost like something out of a detective novel the way he was buried in almost a burglarproof grave. The family, when they arrived at the cemetery, suspected grave robbers had been at work in the cemetery because they saw a grave near his that looked like it had been rifled.

The author enjoys a mud run.

Photo credit: Todd Harra

So, Scott Harrison was buried in a grave dug extra deep; instead of six feet, they dug eight-feet deep. They sealed the bottom with a brick vault. They put his coffin in, and then they covered it with a stone that was so heavy, it took 16 men to lift it and place it over the coffin. They poured concrete over that, and then they hired a night watchman to watch the grave.

You know what they discovered the following day at the medical college? They discovered his remains hanging from a windlass in a dissecting theater. Wow. Right? So, how did they do it? Well, it’s revealed in the book. But it’s just a fantastic story that almost seems like fiction. I mean, this doesn’t seem like a real part of our history, but it is.

Where may readers find your book to purchase?

They can find it in any brick-and-mortar bookstore. Definitely support your independent bookstore if you have one in your town. They can also find it anywhere online, including Amazon and Barnes and Noble. If people like having their books read to them, T. Ryder Smith did a dynamite job narrating the book.

How Did the American Funeral Come to Be?

How Did the American Funeral Come to Be?

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”