Today SevenPonds speaks with Dennis Kowalski, a nationally registered EMT-Paramedic for the city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In the field, Dennis frequently encounters emergency life-or-death situations, and has years of experience attending to those in crisis. In addition to his work as a paramedic, Dennis also works as a firefighter, an instructor at the Milwaukee Fire Academy and as the director of Cryonics Institute (a non-profit organization specializing in cryopreservation after death).

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

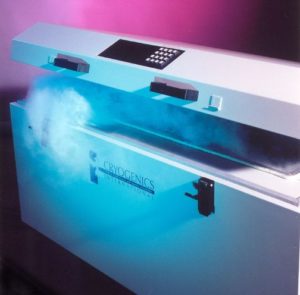

Credit: Dennis Kowalski

Marissa Abruzzini: Earlier in this interview, we were talking about steps that people can take to prepare for emergencies. In addition to your work as a paramedic, you also work closely with cryonics (the process of cooling bodies after death with the goal of reviving them at a later date).

If someone wants to be cryopreverved, do they have to take any special steps to prepare? Is it similar to having a DNR in place?

Dennis Kowalski: The process is very similar to DNR. To prepare, you have to understand some background first.

Everyone dies the same way — your heart stops. When your heart stops, in traditional medicine, that’s it, unless you do CPR and start it again. But how we define death has changed. It’s no longer a single “event.” It’s a process. The brain and tissue starts to degrade, and that takes time. The time it takes is related to our chemical reactions. Temperature slows down, and so does molecular movement. The idea behind cryonics is that you can slow things down and buy yourself time. If we cool someone down who needs surgery, then this improves their chances of survival. This is called therapeutic hypothermia. In cryonics, we take it a step further. By cooling down the body, not only are we giving surgeons at a hospital a chance to save the patient, but surgeons at future hospitals as well.

So there’s just as much prep involved, if not more, than DNR.

Marissa: Can certain medical emergencies negatively impact someone’s eligibility for cryopreservation?

Dennis: If something happened, and there was a great deal of trauma, then I don’t know if there’s anything we could save. There are essentially three different ways that you can die, and each of them will impact your eligibility for cryopreservation.

First, there’s a planned and witnessed death. A good example of this is when you die from a terminal illness. In this case, you can get the equipment on-scene before death occurs. Because you can be put on ice immediately after death, then cryopreservation can start right away. In cases like this, we can protect the tissues, essentially locking them into place without ice crystal formation.

The second type of death is one that’s witnessed but unplanned. This may happen if you have a heart attack in a public space. People are there to witness the death, but we don’t have the cryopreservation equipment already set up. As a result, there’s some delay and some tissue damage, but it’s not going to ruin your chances at successful cryopreservation.

The third type of death is unwitnessed and unplanned. A good example of this is if you have a heart attack while on a hike in the woods, and you aren’t found for days or even weeks later. You’re going to be in bad shape, as far as tissue damage is concerned. In some cases like this, freezing won’t work. DNA is extremely hardy. But you’re more than just DNA. Nerve structures are delicate, and 12 to 14 hours after death, the degradation of these structures might be too extensive. Even if doctors manage to revive you at a later date in the future, you may not regain all of your memories or functions.

Marissa: Getting back to your work as a paramedic and firefighter, what are some of the most difficult decisions that you’ve had to make in the field?

Dennis: One of the most critical decisions is whether to go or stay in place. If we can administer something in the field that can fix the problem immediately, we’ll do it. We can bring the hospital to the patient. But there are some things we can’t do, like surgery. In those cases we can give the person support and fluids, but they still need a surgeon. So we don’t “stay and play,” we go. There are careful protocols and algorithms that we follow, which make these decisions easier. The tougher decisions tend to be when someone has an altered level of consciousness. They can’t tell you what’s going on. I like those because I’m making a bigger difference. It’s not a cookie cutter recipe case. It requires some quick thinking.

Sometimes you don’t get things right. You can’t know everything. You don’t have X-ray vision. If a patient is lying about something, or something is withheld, then you have no control over that. But as long as you did your best, you feel good.

Marissa: Does this work take an emotional toll on you?

Dennis: For the most part, I’m able to compartmentalize. I’ve had to deal with children who have been abused or killed. The only times when it affects me is when it reminds me of my family. I was once carrying a kid from a fire. He had the exact same weight and feeling as my son when I carried him to bed the night before. That really messed with my head. The paramedics who internalize it often have problems. All I can do is the best I can. I can’t save the world, so I try to remember that.

If you missed part one of Dennis’ interview, you can read it here.

How Do Emergency Medical Situations Impact Cryopreservation?

How Do Emergency Medical Situations Impact Cryopreservation?

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?