Credit: Courtesy of J’aime Morrison

In 2015, J’aime Morrison lost her husband, Jim, to brain cancer. Morrison, who is a professor of movement and theater at California State University, Northridge, has a long history with dance and movement – including classical ballet, choreography, modern dance, surfing, and working with actors in experimental theater. Jim’s death was so overwhelming that she turned to surfing and dancing to address her grief through movement. In the process, Morrison found herself motivated to support others in their grief as well; to help them rediscover ways of coming back to their bodies and to express their grief physically.

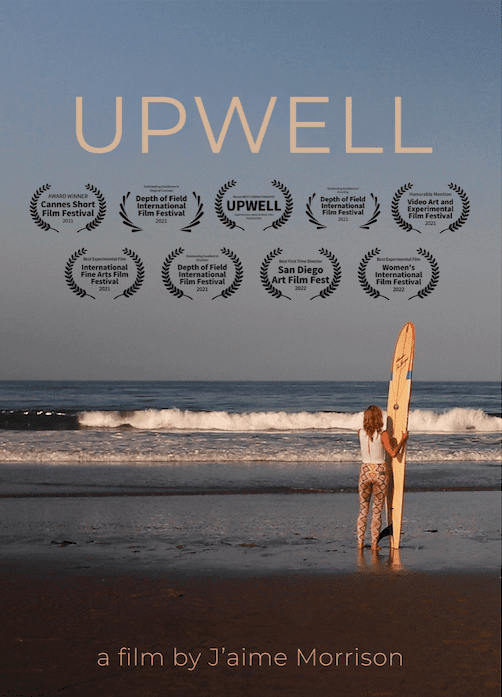

Today, Morrison offers workshops on movement and grief as a dancer, choreographer, educator and — most recently — a filmmaker. Her short film based on her grieving process, Upwell, has won multiple awards, including “Best Experimental Film” at the International Fine Arts Film Festival 2021 and “Best Cinematography” at the Los Angeles Experimental Music and Dance Film Festival 2020.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell me about your background in dance and movement?

I’ve been dancing my whole life. I’m from Santa Barbara, California, and I was in the Santa Barbara Ballet Company as a teenager and did a lot of touring with classical ballet companies. Later, as a dance major at UCLA, I was introduced to modern dance, and that’s where I learned choreography skills and had the opportunity to work with visiting artists like Bill T. Jones, who came to the school and set a piece on us. I just really fell in love with his work. Also, Margie Gillis is a Canadian choreographer whose work I really admired. Then my journey took me to Ireland, where I was getting my master’s in theater, and I fell in love with Irish theater. I started to hear language as music in some of the Irish plays that I was studying, and I was particularly drawn to the work of Samuel Beckett. I did my master’s thesis on Beckett and the female body, and I ended up developing an evening of dance inspired by some of his prose. And so that idea of being drawn to the rhythms of language and using language as music moved me in the direction of theater.

I went to New York to get my Ph.D. in Performance Studies from NYU, and I lived down the street from an experimental avant-garde theater company, called Mabou Mines, where I became a resident artist and was mentored by Ruth Maleczech. There was a real sense of community, and their influence, in addition to going to NYU and studying experimental theater with Richard Schechner, shaped my approach to physical storytelling. Now, I’ve been a professor of movement at Cal State University, Northridge, for over 20 years, and have had a lot of experience teaching movement for actors, as well as teaching dance and choreography, and really thinking about how we communicate through our bodies. It was a natural expansion of that inquiry that led me to think about the idea of grief as an expression of the body.

At what point did you realize that movement was an effective method for processing grief?

Unconsciously, I’ve been processing grief through movement my whole life. My father committed suicide when I was a teenager, and I took a lot of my pain to the dance floor. It was a way for me to exercise the grief, and sort of lose myself in the movement. After losing my husband, my grief process was very different, and I was at a different stage of life. The sense that I could process my grief in a more organic, internal way, through movement, was something that came to me. And then through my own grief process — which included surfing, not just dancing, as an embodied practice — I found that I was drawn to consider how I could help others through movement and attention to the body in grief. I got some solace through reading, podcasts, yoga and meditation, but I wasn’t finding many movement-related resources out there.

How old were you and your husband when he died?

I was 46 and my husband, Jim, was 53. He died of a brain tumor. It was a long illness, and there were many different phases of losing him. My husband was a very active, physical person, and the fact that he was slowly losing his ability to move and to walk hit me very deeply. When he went from a cane to a walker to a wheelchair to the bed, it was so crushing to be watching him lose something so precious to both of us. He did maintain his personality and mental abilities throughout, and I’m very lucky that he did.

We have a very unique story in the sense that my daughter was born over the course of his illness. I was pregnant when he was diagnosed, and then he went through his first year of chemotherapy while I went through the nine months of pregnancy. She was born on the day of his last chemo treatment. She was five when he died, so that’s been very hard in so many ways.

Has losing your own father at a young age informed how you help her to process her grief?

Yes and no. I know the journey that she’s going to have, and it’s so hard. I think that losing your Dad at 13 is a little bit different than losing your Dad at 5. She remembers a lot, and has a lot of really warm memories and sensations, but I wouldn’t say that her memories have been scarred or taken away from her. Whereas I really felt that the presence of this person had just been ripped out of my life. So my experience was somewhat different – but yes, I’ve been able to let her know that I can share a little bit of what she’s feeling.

Why is dance and movement an effective way to process grief?

Losing my husband was extremely hard because it was like losing a lot of my identity. I use this image of being taken down to the studs and then having to rebuild myself back up. And ultimately what I found is that healing is a creative practice. My most natural form of creativity is movement. Our bodies hold things – memories, feelings, traumas – that don’t always necessarily rise to the level of language. We may not have the tools to able to communicate in that way. I really feel that movement, whether you call it dance or just movement, can express things that are nonverbal, and that we can learn from those things without ever having to put them into language.

How do you believe that movement can help with physical symptoms? You’ve mentioned that you had vertigo following your husband’s death.

Moving was not the thing for the vertigo – you lay down flat! But I had sensations like my skin was being peeled off, I had sensations of being very heavy. Being numb. Having trouble breathing, panic. I think breath as a movement can be very helpful – not to just think of it as something we do, inhaling air in and exhaling it out. But to think of the whole body being breathed, and kind of letting it expand throughout the body so that the whole body is in motion. Connecting to an internal heartbeat. I think that connecting to different rhythms inside and outside of the body was a tool for me to trick my brain into forgetting about the pain that I was in.

Women process through movement at a Mourning Surf grief retreat in Costa Rica

with TwoCan Retreats.

Credit: Courtesy of J’aime Morrison

For many people, grief can be paralyzing. For those who are not typically active, what might be a good way to start moving?

I’ve worked with a lot of people who don’t consider themselves dancers or even movers. The people who sign up for my workshops are really brave, because many of them don’t even know: What is movement for grief? It’s such a broad term, and it could mean so many different things. Yet everybody’s individual movement can be so beautiful when it comes from a place of expression. To get there, some of the things that I like to do are opening the arms wide and then closing them in a self-hug. Tensing up certain parts of your body and then relaxing them is very good. Even the organic sense of rocking, when you’re on your back – it releases tension in your neck and upper back and gives you a sense of motion. Standing, you can sway side to side – it’s very simple, you’re just transferring your weight from one foot to the other, but it can be very meditative and comforting.

What would you say to people who feel self-conscious doing movement, or believe they can’t dance?

It’s really about feeling what’s inside and not about how it looks. That can really take away that sense of judgment, which is often rooted in trauma. When people are with me in a workshop and doing their opening meditation, I say, “Feel your body.” Even for me, that invitation to actually feel my body – it’s so unique for people to actually attend to. We’re so busy, we talk over the body, and we’re so good at distracting ourselves from our body, our instrument. It’s the same for actors, too – how do you listen to your body? And to really practice feeling. It’s so hard with grief, because it is so painful to feel. But if you can allow yourself to just listen to or feel what your body is telling you in that space, that’s a great place to start.

What kinds of grief do people bring to your workshops?

There can be many different kinds of grief being brought to the workshop and addressed. I once had a gentleman who was grieving his wife – he was the only man in the workshop, and was like, “I’ve never done anything like this before.” There were people grieving pet loss, there were people grieving the loss of themselves – previous iterations of themselves. An array of different kinds of grief. And yet when you grieve together, and you move together, you share something, and it’s a great leveler. There’s a common ground and acceptance that’s so beautiful in the grief space. That’s a little harder to achieve during a Zoom workshop, when many people have their cameras off. But at the same time, I understand. I’ve had workshops where people say, “My husband died a week ago.”

How do you decide on the specific movements that you incorporate into your grief workshops?

I have a whole curriculum of classes, and I tend to be really thematic. My recent workshop used the metaphor of mapping – doing a body scan; physically locating where we’re feeling grief show up as love, trauma, anger, or sadness; and then using these sites as a score for movement. I have another workshop that involves thinking about presence and absence, and how we can move into absence with presence. And I have a workshop that’s all about rhythm, music, sound and silence — thinking about Miles Davis, and how the music is actually between the notes; how this period in our life is sort of like a lull in surfing. How can we give shape to that space in our lives? These are some different things that I’ve wanted to explore, and then the movements come from that.

Can you tell me about Mourning Surf?

Mourning Surf is a company that I founded, emerging from an award-winning film that I made called “Upwell.” The film uses dancing and surfing to embody my story of grief. After Jim died, I went down to Costa Rica for a solo surf trip, and it was very hard – I cried the whole time. But I had a wonderful time, and I came back feeling very empowered. I’d been able to surf. And I’d had a massage there – the woman massaged the front of me instead of the back, which was very surprising. She told me that I had what was like a cage around my heart, because the muscles were so thick, and the experience kind of burst everything open. Then on my flight back, there was a woman whom I greatly admired named Kassia Meador, who’s a beautiful surfer, and I went up to her and asked her if she would be in my film. And she said “yes.” So it’s a short experimental film, and I got a bunch of my girlfriends who surf to be in it. It really helped me, it was very therapeutic for me.

Credit: Courtesy of J’aime Morrison

The first title of the film was “Undertow,” because it was about how I felt submerged by grief and I was getting pulled by the undertow, flailing around in the washing machine of the waves. But gradually, through the process of making the film and meeting new people and learning some new techniques, I became more hopeful. I heard my cinematographer talking about this term called “upwelling,” so I looked it up, and it refers to when nutrient-rich water comes in and replaces the old water – as well as the upwelling or swelling of emotion. It seemed like a perfect metaphor for what I was trying to do, so I changed the name to “Upwell.” In the film the viewer’s perspective shifts from underwater, to whitewater, to above the water with drone shots. So there’s an upswing in the gaze of the viewer as well.

Through that, I developed the idea for Mourning Surf Films — a creative outlet where I can bring together movement and surfing. It’s sort of a play on words because in the morning you look for a surf report of the waves. So a Mourning Surf Report would be: How am I feeling today? What are the waves of grief doing? After Jim died, the mornings were the hardest for me, because we had this ritual of always having coffee together after our daughter would go off to school. I couldn’t just come home anymore, so I would drop her off and feel like I had nowhere to go. I would go to the beach, and I would surf, or I would just watch the surf. And of course, the sea is able to hold it all.

Morrison at home in the ocean.

Credit: Courtesy of J’aime Morrison

You seem drawn to the healing power of the ocean, and I wanted to ask how that has informed or affected you as well.

That’s been a huge part for me, and I’m lucky to live near the ocean. Some days I would just lay on my surfboard in the sand and release myself into the surfboard and cry. And then some days I would paddle out and cry in the ocean, and feel that the tears were mixing with the ocean. It was very cleansing for me. Some days I would go out and the water would be like glass – it would just be a mirror reflecting back all of the grief. But the most significant thing for me was when I would paddle out, and I would stare at the horizon line. And I would think, if that’s out there somewhere, there’s an out there for me, too. I can keep going.

I also love being in the water.

Yes, swimming, surfing – I’ve always been drawn to going in rivers and lakes wherever I am. I’ve always been a water person. There’s a beautiful book called “Why We Swim,” by Bonnie Tsui, and she has this lovely line where she talks about how immersion releases our imagination. I feel so connected to that way of thinking – whether it’s swimming or surfing or just splashing around. It releases something.

I’m part of this group called Waves of Grief Collective. Every second Sunday we hold drop-in meetings for anyone, all up and down the coasts of Washington and California. They’re all about coming to the ocean, bringing whatever grief, whatever loss you’ve experienced and holding a space for that. It’s a beautiful group.

Is there anything you’d like to add that I haven’t asked and that you think is important?

What I’m really interested in is how we come back to our bodies. We all have a different way of doing that, but it seems so important to come back to that process.

It seems that a lot of people are not in their bodies even if they haven’t experienced a loss. There are a lot of people – I used to be that way – who are so distanced from their own bodies that they can’t feel what’s going on inside of them.

Well, people refer to the gift of grief. Maybe that is something that grief can help us with, because it can be such a physical experience. Maybe that’s an awakening to a broader physical experience in one’s life.

That’s so interesting. Is there one final thought you’d like to leave with people about movement and grief?

Just close your eyes and move.

Surfing the Waves of Grief

Surfing the Waves of Grief

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”