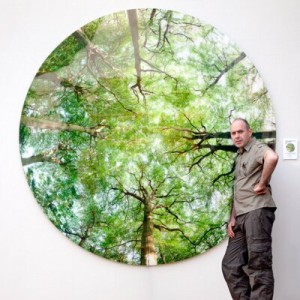

SevenPonds speaks with the Dublin-born, UK-based photographer David Anthony Hall. David’s work inspires its viewer to reflect upon his or her relationship with the natural world, and his sprawling photographs of woodlands have been recognized worldwide. But amongst his proudest achievements is his work’s relationship to hospice environments and cancer research. Through permanently installing his work in hospice centers (such as Marie Curie Hospice in the West Midlands, UK), he has consequently become a pioneer of sorts in an important mission: to make hospices not just inhabitable but uplifting.

MaryFrances: How did you get started in photography? How would you describe your work?

David: I got involved in photography in school when I was about 12. I started off by printing my dad’s old negatives – well, one of my dads. A lot of my relationship with photography extends from the fact that I was adopted.

There are five kids in my family and four of us are adopted. Dublin, Ireland is a very small place. There was always this suspicion that you might run into someone who could be your relative. What I loved about photography was that I could be a voyeur, hide behind the camera, take pictures and study them afterwards. I could wonder where I fit in. It was a perfect medium for me to explore my environment, consider my origins and express myself.

MaryFrances: So how did a relationship between your photography and hospice environments come about?

David: My relationship with hospices goes back to when I was a young teenager. My friend Margaret was diagnosed with cancer. She fought it bravely for seven years, but eventually succumbed to the disease. I would visit with her at every stage of her journey, which inevitably ended in a hospice.

It was ultimately very sad as Margaret Browne (1955 – 1987 RIP) was so young and full of life. I would visit her in those last months of her life there, and I always had this dread upon entering the building. Architecturally, it was a somber, dreary place — a former religious building hidden away and badly landscaped. I mean, we’re talking about a building dating back to the 1970s in Dublin. There was just nothing appealing about it.

After studying Photography at art school, I went on to have a career in still life photography in London, which I retired from in 2000. I returned to landscape photography again in my thirties, which coincided with finally meeting my biological parents. My work did well in London galleries. But I didn’t just want to make pretty pictures, I wanted to do something that could help others. I guess I considered myself to be very lucky in life, and I wanted to return something that could promote healing and well-being for people. I also wanted to show a depth to my work, so I started specifically selling work and donating the proceeds. In 2009, I created the largest picture of its kind in the UK, which I dedicated to the memory of my biological father, who died in 2007 of cancer, and I split the $13,000 between Cancer Research UK, Macmillan Cancer Care and the cancer wing in Barth’s Hospital. It felt very good at the time and was, I feel, a wonderful way to mark my natural father’s (Antonio Senezio 1934 – 2007 RIP) life and thank him for giving me mine.

MaryFrances: How do you think photography fits into palliative care?

David: Well I think art in itself is healing. Art was always one of my strong points, and I think being able to express yourself or explore your creativity is very cathartic, regardless of ability. Photography speaks to that because you get instant, brilliant results and with the scale I finish my work, it can transform and humanize even very large spaces.

The context of palliative care and photography is also one of a historical document, I think.

MaryFrances: How so?

David: Well it’s something that allows patients to reflect: Art is a window to the mind, the subconscious, allowing us to escape reality conjuring up all sorts of memories which can open a portal to allow the viewer to look over their lives to look over their relationships with loved ones. In the context of hospices, for example, one can make a kind of picture wall that allows someone to bring together all the aspects of that patient’s life.

David’s 3 Tips:

1) Make art! It becomes a keepsake for loved ones — something to pass on.

2) You don’t have to be an “artist” to express yourself creatively.

3) Spend more time in nature!

Mary Frances: Do you think hospices in the UK are supportive of bringing art and creativity into play?

David: A lot of UK hospices have art and craft rooms where people are encouraged to explore their creativity. I believe it as well as art therapy and outreach programs are considered when applying for Art Council funding.

MaryFrances: How did your collaboration with Marie Curie come about?

David: Well, at the time I was still donating money from the sale of my photographs, and as a continuation of that I started to wonder, what if I could do something even more direct with the hospices and the works? I was creating mural-esque photographs, and they fit very well into the otherwise blank hospice settings.

As I’ve mentioned, cancer has played a big part in my life. All my natural father’s family have died from cancer. Indeed, since his death, his remaining siblings have died as a result of the disease. Now, having only known my biological mother (Maura O’Connor 1951 – 2011 RIP) for 5 years, she was diagnosed with cancer. The news came shortly after Antonio had died, and for her at 56 it was devastating. By this stage, I had been working with Lady Cotton, Head of Special Events at Marie Curie, through my donations to an annual event at the Royal Academy in aid of Marie Curie when I heard of the plans for their new hospice, and we talked over possibilities of installing my work there. It was my first collaboration with a hospice in that way, and although I was partly commissioned for the work I produced it stands as my largest single donation and is one of my proudest achievements. HRH Prince Charles officially opened the Hospice in June 2013.

MaryFrances: What are your hopes for future hospices in relation to the integration of more creative, artistic outlets for well-being?

David: Generally the thing about new hospices here in the UK is they only ever budget for the building delivered with the walls painted white! They don’t budget for art, which means work needs to be retrofitted. This holistic creating-an-atmosphere approach is either not considered, has no funding or is left to individual self-employed artists to supply work free of charge. I hope to lead by example by showing how important art is in the context of their buildings. It’s important, for this to happen, that there are no budget constraints. As where money is involved, compromises have to be made and often it is these compromises that add up to deliver poor hospice environments, thus adding to the problem. I want people to build the art with the buildings, for it to be a collaboration — to conceive and build the pictures into the walls. Not only does that save cost but it opens up the possibility of collaboration with architects, staff and patients.

MaryFrances: Can you recall a moment when you really started to reflect about death, or the “bigger picture” of things?

David: My gran (Ellen McEvett 1900 – 1981 RIP) died on the 16th January 1981. Two days later, on my birthday, she appeared at the foot of my bed. Growing up in Catholic Ireland, there was this unspoken notion that if you “did everything right,” everything would “be alright.” Losing Margaret when I was so young really impacted me – she was such a young, healthy girl — and it was the beginning of many experiences with cancer for me, of being in hospice environments to support those I love.

As our lives advance at certain stages, we become more aware of things. For me, I think it was also having my kids. When my dad passed away (Bernard (Brian) Hall 1931 – 2013 RIP), my five year old son said rather matter-of-factly, “Grandad is extinct.” It really struck me, because he could comment on it so frankly. In the context of our lives, things affect us, but it’s only at certain stages in the journey when we become more aware of ourselves.

MaryFrances: How did you decide on which photographs to put into the hospice facility? Was the focus on trees and the natural world something that had already interested you?

David: It’s all intertwined. Like I said, for quite a while I had stopped taking pictures. When my biological father was diagnosed with cancer, I used my photography as a kind of cover for my motives, that to be available to support him during his treatments without seeming overbearing. I wanted to be there for him, especially as I knew he wasn’t coping well. I could travel to see him on the pretense of taking pictures.

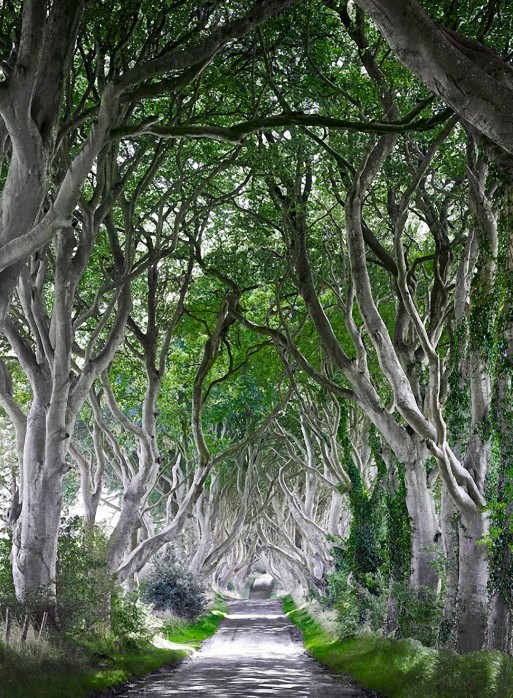

I would go to see him in the hospital, and then I’d head off to the woods to take pictures. And that’s the heart of the connection: the antithesis of being in the hospital was being in the woods. It can be a spiritual place, I think. A retreat. You know, research is showing that even glimpses of nature for medical facilities can help patients with healing and attitude – and I can definitely relate to that. I think that’s why my images work so well in a hospice environment.

MaryFrances: What would you say to those who think art is an afterthought when it comes to hospice design?

David: Well, consider this: you present yourself at the hospices in wintertime, and regardless of the new and wonderful hospices that are being built with gardens, there are inevitable seasonal changes. In the winter, it’s pretty awful. In the rain? Also awful. With my photos, you’re allowed to have spring 365 days a year. You’re creating an inviting place. And I think it’s good for the staff of the hospice – of course the clinical equipment available is most important to have, but what about the atmosphere of the place? I think it also shows a kind of respect for the staff, helping to transform their working environments with the power to take their walls outside. For accompanying adults and visitors, my images are uplifting, providing a calming and soothing distraction.

MaryFrances: What has working with nature taught you about mortality?

David: It has grounded me in a good way. You realize that everything dies in the fall and is reborn in the spring. As more and more of us move to cities, we lose touch with nature’s ways. It’s natural for us to die. It’s a miracle for us to be born. We are all made of stardust.

There’s a feeling in Ireland where we celebrate funerals and cry at weddings (laughs), but I really do think it is good to celebrate someone’s life. No matter how close we are to someone who’s passed, it shouldn’t be such a debilitating reality to the people who are left behind – because that’s just it, it’s a natural reality.

MaryFrances: It’s a very humbling and comforting experience.

David: Being in nature helped me make sense of what was happening. The woods can be a wonderful metaphor for human nature, I think. When a forest evolves, new space has to be made for light, otherwise nothing is going to grow there. Trees have been around for hundreds of millions of years, [they’re] time-travelers, really! They’ve shaped us and our planet. They fulfill our basic needs for survival. They allow us to breathe; they recycle our water and store our carbon. They are the raw material of both construction and fuel, and they are symbols of our relationship and weight on the earth. Furthermore they’ve taught me to look at my life and human existence in a greater context.

MaryFrances: Thank you, David.

David: Thank you.

What Do Trees and Hospice Centers Have in Common? An Interview with David Anthony Hall

What Do Trees and Hospice Centers Have in Common? An Interview with David Anthony Hall

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento