Today SevenPonds chats with Holly Pruett, a life-cycle celebrant based out of Portland, Oregon. Holly is a certified Life-Cycle Celebrant through the Celebrant Foundation and Institute. She helps her clients find a way of telling their stories at pivotal times in their lives through ceremony and ritual.

Juniper: What drew you to work as a celebrant, particularly around the transition of death?

Holly Pruett, life cycle celebrant

(Credit: deathtalkproject.com)

Holly Pruett: As I look back over my life I can see one thing leading to the next. My father’s dying 15 years ago without any funeral, memorial or grief ritual of any kind was a very big event for me. I had no idea at the time that there was an option like civil celebrancy. Having had to devise a grief ritual for myself with the help of friends, I found myself wanting to understand how we can support each other in making meaning during key times in our lives. When I heard about the Celebrant Foundation and Institute, I saw that there was a pathway to build some practices. It felt like a natural fit.

Juniper: How did you navigate the experience of your father’s death? How did your community help you develop a ritual for yourself?

Holly: My friend had a pagan practice and a sense of how to create a ceremonial container. As someone with experience in facilitating others, I knew it was important for me to put myself in someone else’s hands. The first step for me was saying, “I need help and I don’t know how to do this.” So he helped me discern what the right day and time would be based on the needs he saw at the time. Then I was able to focus on what I needed to say to my father through the ceremony — what I needed to give voice to and have witnessed. I was also able to see why it was important to me to have certain people there as participants and what I was asking of them. Trusting my friend to hold the ceremonial container allowed me to focus on what I wanted to shift through the ceremony.

Juniper: Did the ceremonial container and the people present help you think and feel more clearly through your process?

Holly: Yes, it felt a like rite of passage for me. I confronted the fact that my father was largely absent in my life while he was alive, and had to question what a relationship can be when the physical is no longer available. In many ways, the ceremony didn’t serve to fully memorialize him. My later celebrant training helped me realize that my father never had a eulogy. So on the 10th anniversary of his death, I went back over his life and various people’s experiences of him. I then put together a tribute to help me see him as he was in the world, separate from my own grief process. This experience of navigating my father’s death helped me realize some things that have become central tenants in my professional practice as a celebrant. Notably, it’s never too late, and a ceremony can’t always meet all needs. We have the capacity to continue having relationships with our dead, and to serve those relationships in a variety of ways.

Credit: star-telegram.com

Juniper: How do relationships shift when the physical aspect is no longer present, and how can a celebrant serve to clarify that adjustment?

Holly: I often think of myself as having the privilege of being the first person to meet the deceased in their new form. I’m not speaking metaphysically, but of the shape they left in the world: the stories to be told about them, the tremendous grief of the people in their lives, and the photos and memorabilia. In meeting with the family after a death has occurred and letting them share all those pieces with me, I’m helping them transition from their embodied relationship to that person toward relating through the memory of their presence and the artifacts of their lives.

I remember one client in particular, whose mother had dementia for several years before her death. She had been her mother’s primary caregiver and witnessed her mother’s shift away from the person she had known. Through the creation of her mother’s memorial, she was able to feel closer to her mother than she had during the last years of her life. Through ceremony, she was able to connect back with and uphold the totality of who she knew her mother was.

Credit: bbc.com

Juniper: When you create a ritual or ceremony, what is your starting point, and what are the elements you take into account when considering how best to serve a particular individual or family?

Holly: First I try to get a sense of the what the client needs in a particular situation, and what their goals are. For instance, is this a bereavement ceremony to express grief and offer solace to people who are trying to go on through a challenging time? Not many people are seeking that. I often hear, “We don’t want to be sad. This is going to be a celebration.” I work with people to create what they want. I won’t force sadness upon them, but I will be holding space to normalize sadness within any given situation. Our grief is another form of praise. If we are celebrating someone’s life, our grief can be part of that. Holding that belief myself, I try to open the door so that something that’s not very popular within our dominant culture can be given space to breathe.

Credit: deathmaiden.blogspot.ca

Sometimes I have the opportunity to speak with someone in advance. For example, I may meet someone who has a terminal diagnosis, or who wants to spare their loved ones from figuring it all out in a future time of grief, or family members who are anticipating a death. In those instances, I will introduce them to a fuller continuum of possibility to care for a loved one in death, apart from the funeral or memorial. Will they spend time with the body and wash it? If the family plans on cremation, will anyone want to be present for that? Might they play a role in adorning a shroud or coffin? Lots of people haven’t considered all these stewardship roles and levels of engagement that used to be the providence of family or community members, and which are now largely outsourced. Often people will say, “No, I don’t want to do that.” But when the time actually comes, they find that something has awakened in them that changes their mind. I see what I’m doing as a way to reignite our cultural imagination about what caring for each other might look like.

Today SevenPonds shares part two of our conversation with Holly Pruett, a life-cycle celebrant based out of Portland, Oregon. (Read part one here.) Holly is a certified Life-Cycle Celebrant through the Celebrant Foundation and Institute. She helps her clients find a way of telling their stories at pivotal times in their lives through ceremony and ritual.

Juniper: How do you navigate intersectional and atheist beliefs around what honoring the beloved dead should or could look like?

Holly: People will often say that funerals are for the living. And I appreciate that for people like my dad, who said he didn’t want a funeral, this is a kind of antidote –a way to validate what they want for themselves.

But I wonder, are they just for the living? Most cultures throughout time have held that we, the living, have a responsibility to the dead. And that has something to do with how we conduct ourselves. I don’t come with any of my own orthodoxy about how to do that. Nor do I want to dictate how it might look. But I think we’re orphaned at this time in the dominant culture, where the prevailing sentiment is, “It’s my life; it’s my death, and I’ll celebrate it how I please.” We haven’t had the opportunity to think about a bigger picture.

I’m wondering about these things myself. When I find clients who are open to wondering about them too, there’s a lot of richness that can come through an organic unfolding of ceremony. For those people who don’t want to explore that, or don’t feel capable of approaching what needs to happen at the time, then we do our best to meet their more immediate needs.

Juniper: Does part of the way that you serve people with ritual and ceremony include creating practices for people that they can do independently. For example, do you help create rituals to help families have an ongoing relationship with their loved one?

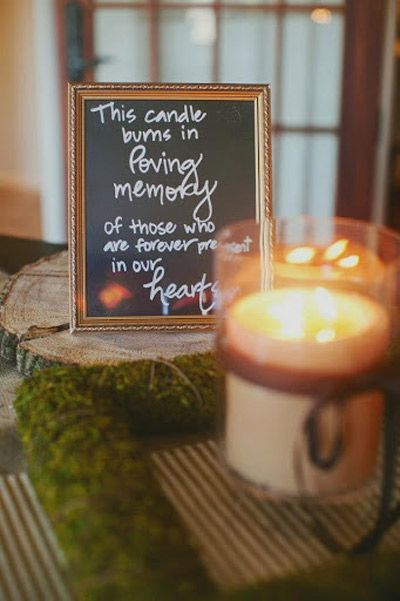

Holly: I try to support the development of a culture of remembrance within a family or community. This might include looking back into their own cultural heritage and family traditions to see what might be reinvigorated to create a contemporary ritual. That could be as simple as beginning a ceremony with the lighting of a memory candle and speaking the names of the ancestors who preceded the person being mourned. It might be the incorporation of family heirlooms, such as a quilt that had been made by someone in the family who has died in the distant past. We might also consider whether parts of the ceremony can honor the person’s birthday, the anniversary of their death and other times of remembrance. To follow the candle example, that practice might continue at other family gatherings, such as to mark an empty seat at the dinner table.

Credit: pinterest.com

When I work with families, we seek to find practices that resonate with them personally, and also to think backwards as well as forwards in time. I just worked with a woman whose deceased husband had been prominent in his community. There was a portrait of him hanging in a public place, and I wondered if bringing flowers to that portrait on an important anniversary might be a way to create an ongoing relationship to her husband. It might also form a connection to those people who would come by and see those flowers and realize that this person’s legacy was still serving the community.

Juniper: Do you find that your clients have an interest in their ancestry and family history sparked by the death of a loved one?

Holly: I think some do and some don’t. If we’re dealing with a sudden or traumatic death such as by suicide, or the end of an exhausting period of care giving, there are a lot of elements that can come to bear upon a family’s capacity to cope, including being internally divided among themselves. Different spiritual beliefs within a family are also a big presence in the process. So, there are times when ancestry becomes a natural opening point in understanding the death that’s occurred within the bigger story of the family. And at other times, there just isn’t room for that.

Juniper: As a celebrant, how do you navigate the differences in perspective among individuals in a group you’re serving — someone’s blood or chosen family? I mean differences such as worldview, how they want the ceremony to look or not look, as well as understanding the nature of the Great Mystery?

Credit: japanvisitor.com

Holly: My practice as a celebrant definitely bears the marks of our time. That is, we’re in a customer-satisfaction culture and a marketplace of ideas where anything goes, and we’re each the author of our own story. So, there are many ceremonies where there isn’t an overarching set of beliefs. They are not guided by something greater than the individual preferences of the people involved.

I differentiate between different kinds of ceremonies. I’ll help people put together a ceremony that comes out of a more intact culture, where individuals don’t make up their own ceremonies. But, given that we’re in the time we’re in, it’s sometimes necessary to create a dual context. For example, some family members who hold certain beliefs might offer a prayer coming from that position, while the overarching ceremony isn’t framed from that perspective. I aim to create hospitality for all the different pieces that are important to the people I’m working with, to give everyone a seat at the table. There are also times when that is not possible. In that case, we hold the ceremonies separately.

Juniper: Thank you for your work and insight. It was a pleasure chatting with you!

Holly: Thank you!

What Is a Life-Cycle Celebrant? An Interview With Holly Pruett

What Is a Life-Cycle Celebrant? An Interview With Holly Pruett

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States