Lilley with his father, a two-time heart transplant recipient.

John Lilley never expected to work in organ donation. After leaving active duty as a U.S. Air Force paramedic-firefighter in 2001, he’d hoped to find a similar role as a civilian. But then he interviewed for a position as a clinical procurement coordinator with California Transplant Donor Network — now Donor Network West — and was hooked. Nineteen years later, Lilley is vice president of organ operations for the organization, which serves more than 13 million people in Northern California and northern Nevada.

Part of the reason Lilley was drawn to the position was his father, who received a heart transplant in 1988 following a massive heart attack. He didn’t do well, and so he was relisted and received a second heart seven years later. Lilley was inspired to devote his career to organ donation, returning to school for his nursing degree and MBA. Currently, he is obtaining his Master of Science in Nursing as a clinical nurse leader at the University of Nevada, Reno. “I can’t imagine doing anything else,” said Lilley, whose father recently celebrated his 85th birthday.

Lilley with his wife, Jen, at a University of Nevada Wolf Pack game.

When not at work, Lilley, an avid Los Angeles Dodgers fan, enjoys watching baseball, hiking, and spending time with his wife, daughter and four-pound Yorkie.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you describe your current role at Donor Network West?

I oversee the clinical process of the donation cycle. So when a patient is referred to us, we have a team of clinical professionals that goes out and evaluates each potential donor to ensure suitability. Once we have authorization that a patient is a suitable candidate, we work that patient up to determine what organs are viable for transplant. We offer those organs to our transplant centers — not just locally, but literally across the country. My team does all of the frontline clinical management of the patient, all the way through the organ recovery process, with respect and dignity for the gift that’s been given.

Who initially broaches the subject of organ donation with a patient or their family?

The frontline nurses will make a referral; we ask that hospitals not bring up donations. There’s a reason for that, which is that we can then go in and evaluate the patient. A very small percentage of people in the United States are actually viable to become organ donors — less than one percent of all deaths will qualify. You have to die on a ventilator, still being perfused. Most of our patients are either trauma patients or have had a stroke; they meet brain death criteria or are very close to that. A lot of times their medical history will rule them out as a potential donor, or their lab values or how much trauma they’ve sustained. So we ask that the referral be made first.

What happens next?

If it’s determined that the patient is a suitable candidate, we have a team of social workers, a family care team, that talks to families about their options with regard to donation or discloses if a patient has registered as a donor. We’re the professionals that can answer all of those questions: Can I have an open-casket funeral? Who pays for all of this?

Can they have an open-casket funeral? And who does pay for it?

Yes, you can absolutely have an open-casket funeral following organ and tissue recovery. We work directly with funeral homes to ensure that we’re recovering from areas that aren’t visible. And it’s not up to the family to pay for anything. Once we have authorization, we take care of all of the billing from that point forward — the workup and testing to determine which organs or tissues are viable for transplant — and then it’s billed to whichever transplant center receives the organs. Anything prior to our involvement from their hospitalization is still on the patient’s insurance, but the family’s not burdened with the cost of the donation process.

When not supporting organ donation, Lilley roots for the L.A. Dodgers.

What types of organs and tissues can be donated?

In terms of organs alone, one donor can save up to eight lives. That’s a heart, two lungs, two kidneys, a pancreas and a liver. In some cases we can split the liver into two segments, depending on the size and nature of the potential recipient, which can help two people. And then the small bowel is sometimes recovered and transplanted as well.

Literally hundreds of lives can be affected through tissue donation. These include everything from corneas for sight, to ligaments and tendons for sports injuries, to skin donations for burn victims. Tissue can even be used in reconstructive surgery for breast cancer patients. There’s also vasculature, such as veins and arteries, which is used for operations such as coronary artery bypass surgery that really affect patients’ circulation and ability to survive. There’s bone; there’s cartilage; there are all sorts of ways in which tissue can be recovered and transplanted.

We’re also really proud of our research arm, which provides organs and tissues to researchers exploring methods of addressing diabetes, hypertension, brain disease, and even COVID-19. We recover the dorsal root ganglia in the vertebrae, a really sensitive part of the spinal column that is the body’s pain center, in hopes of eventually developing different pain medicines or therapies so that we aren’t so reliant on opioids.

Are there any organs or tissues that are in particularly high demand?

The vast majority of patients around the country are waiting for kidneys due to widespread chronic kidney disease from hypertension and diabetes in the United States.

How is it determined who receives the transplant?

We work with the United Network for Organ Sharing. We put all of the patient’s information — their blood group, their tissue matching, their size, their medical and social history — into a national computer database system called DonorNet. And from there, it generates the list of all viable candidates, and it basically just breaks it down into concentric circles — very close to where the donor patient is, and then out 500 miles, and then another, until we either exhaust the list or the organ is accepted for transplant. We start at the top of the list and work our way down.

What circumstances rule out a potential organ donor? Does age matter?

For organ donation, we go up to age 80 and all the way down to a newborn; a full-term birth, a five-kilo patient. For tissue donation, we can go older — I think we had a 92-year-old skin donor this last year. It used to be that HIV was an automatic rule-out for us. But now, thanks to the law implemented in 2015, we’re involved with transplanting organs from HIV-positive patients into HIV-positive patients. They’re waiting on the list the same as anybody else. Other rule-outs are certain cancers, metastatic cancer — we don’t want to transplant patients with cancer, obviously. But we evaluate every potential patient.

One thing I want to make sure that people understand is this: Don’t rule yourself out. You never know who needs a transplant on that list.

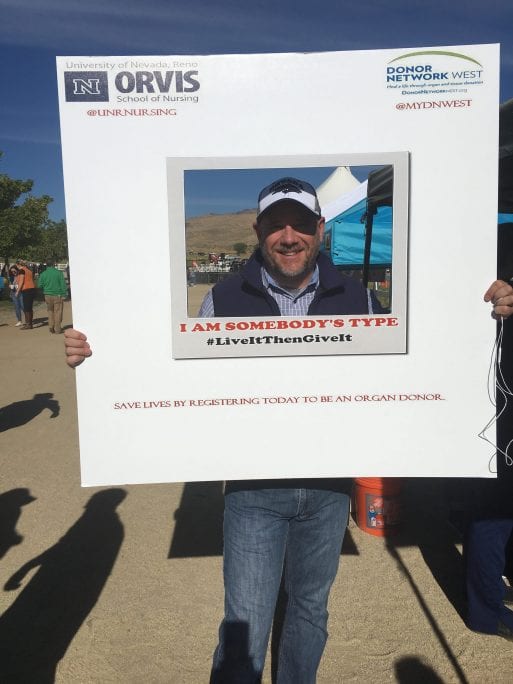

Lilley promoting organ donation at the Great Reno Balloon Race,

of which Donor Network West is a sponsor.

Has COVID-19 impacted your ability to procure and transplant organs?

Right now, COVID-19 is a rule-out for us because we have such limited information. We do multiple tests as part of our workup, and it has to be within a certain amount of time prior to the recovery to ensure that we’re providing the safest organs.

On a national level, we did see a dip in overall donors — especially in northeast New York — but we’ve been fortunate in our area in that we’ve stayed pretty consistent. People were thinking that we’d be shutting down, but we’re essential workers and we’ve been able to complete our mission through the COVID-19 cycle. We’ve outfitted our entire staff with masks and personal protective equipment and have remained open for business.

What can someone who wants to be an organ donor do to ensure that their wishes are carried out by family members?

The first thing is to sign up on the registry. You can do that on our website, or on the websites for Donate Life California or Donate Life Nevada. [See Donate Life America for the national registry.] And when you do sign up, or if you check the box to be an organ donor at the DMV, or put it in your advance directive, make sure to tell your loved ones what your wishes are. We walk families through that process, and 99 percent of the time they realize that the choice fits with their family member’s character. But it really helps to tell your loved ones what your intentions are so that it’s not a surprise.

Lilley with his daughter, Alex, on Father’s Day.

Do the families of organ donors ever have the opportunity to interact with those who’ve received the organs?

Absolutely. We have an aftercare program, and we follow up with our donor families if that’s something they’d appreciate — first of all, just by checking in and connecting as human beings. We’re meeting people at the worst times of their lives — they’re losing their mothers and fathers and husbands and wives and brothers and sisters and children. So the aftercare program contacts families 30 days out, 60 days out, six months out, sometimes even after a year or more.

We also provide the opportunity for them to interact with recipients. Now, of course, we have to be really cautious because of HIPAA regulations. But if both parties want to meet or correspond, we help coordinate that. We ask both families to ensure that it’s cordial and appropriate, and we hope that those families connect. It doesn’t happen as often as you’d think, because for some families it would create too much pain. But many of them do, and I personally know some that consider themselves joint donor-and-recipient families. They go on vacations together, and meet up a lot, and it’s a beautiful thing to see. But we also want to honor people’s privacy and their desires if they want to stay anonymous.

Thank you, John, for sharing your insights on organ donation.

When Death Brings Life: Organ Donation Explained

When Death Brings Life: Organ Donation Explained

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition