A new study published in the journal Stroke suggests that post-menopausal women who consume at least two low-calorie sweetened beverages a day have a higher risk of stroke and other cardiovascular events than those who drink “diet drinks” infrequently. The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking low-calorie sweetened beverages to cardiovascular disease.

Credit: sentara.com

Led by Yasmin Mossavar-Rahmani, Ph.D., an associate professor of clinical epidemiology and population health in the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in Bronx, New York, researchers analyzed data on 81,714 post-menopausal women aged 50 to 79 years. The data was culled from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, which followed a cohort of nearly 94,000 postmenopausal women for between six and 12 years.

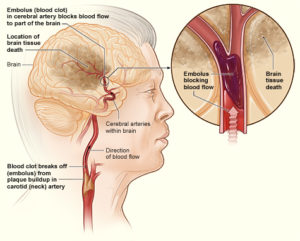

The study relied on subjects’ self-reported intake of low-calorie sweetened beverages, which included diet sodas and artificially sweetened juices. The majority of participants reported infrequent intake of less than one diet drink per week. A much smaller number — about 5 percent — reported drinking at least two low-calorie sweetened beverages a day. This group had a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease and strokes, especially strokes caused by occlusion of small blood vessels in the brain. Specifically, the researchers found that heavy consumers of diet drinks had:

- A 23 percent higher risk of stroke

- A 31 percent higher risk of a stroke resulting from a blood clot

- A 29 percent higher risk of heart disease

- A 16 percent higher risk of death from any cause

Dr. Mossavar-Rahmani emphasized that, because of the observational nature of the study, these results do not prove that consuming low-calorie sweetened beverages causes stroke or cardiovascular disease. It merely proves an association between the two.

Teasing Out Causation

In an editorial accompanying the published findings, Hannah Gardener, Sc.D. and Mitchell Elkind, M.D., M.S. point out the study’s limitations, specifically the lack of data on what actually caused the higher incidence of cardiovascular disease in heavy consumers of diet drinks. Although Mossavar-Rahmani and her team made some efforts to exclude participants with pre-existing risk factors (specifically diabetes and heart disease), there are still many unknowns.

Credit: nhlbi-nih.org

For example, some participants may have switched to low-calorie sweetened beverages after a lifetime of drinking sugar-sweetened beverages, which are closely associated with obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Others may have rarely consumed sugary beverages but began drinking low-calorie sweetened beverages later in life as a strategy to decrease total calorie intake and lose weight. Conversely, some participants may have had a long history of drinking low-calorie sweetened beverages as part of a nutritious diet and healthy lifestyle.

Without studying these subsets, say Gardner and Elkind, it’s impossible to determine what other factors may be contributing to Dr. Mossavar-Rahmani results. Nonetheless, according to Rachel K. Johnson, Ph.D., R.D., Chair of the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee, “This study adds to the evidence that limiting use of diet beverages is the most prudent thing to do for your health.”

Take home message: Drink water instead.

New Evidence Ties Low-Calorie Sweetened Beverages to Cardiovascular Disease

New Evidence Ties Low-Calorie Sweetened Beverages to Cardiovascular Disease

The Other Death in the Family

The Other Death in the Family

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls