Credit: himss.org

Advancements in technology have been proven to work wonders in the healthy aging realm, particularly for dementia patients. Here at SevenPonds, we’ve covered how virtual reality (VR) specifically can benefit both people with dementia and terminal illness. And now, a new study from the United Kingdom suggests that virtual reality can identify the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

Our brains contain a system of cells that act as a GPS of sorts. This cognitive positioning system processes where we’ve been and where we are and helps us get around. A crucial part of this system is known as the entorhinal cortex. This region of the brain is one of the first damaged by Alzheimer’s. This could explain why “getting lost” is an early symptom of the disease.

Currently used written methods/tests used to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive decline are not able to test for navigation issues. So the research team — a joint collaboration between the University of Cambridge and University College London — developed and took to trial a VR navigation test with patients at risk of developing dementia and/or Alzheimer’s. The results were published recently in the journal Brain.

Study Participants

The researchers recruited 45 individuals with mild cognitive impairment from the Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust Mild Cognitive Impairment and Memory Clinics. The team also recruited 41 healthy, similarly aged individuals employed as controls for comparison.

A VR headset

Credit: amazon.com

People with mild cognitive impairment typically exhibit noticeable declines in cognitive abilities such as memory and thinking skills. But they can still function day-to-day and are fully capable of living on their own. However, they are at a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia. Mild cognitive impairment can also be caused by other conditions like anxiety or simply normal aging. Therefore establishing the underlying root of someone’s impairment is pivotal in determining whether they’re at risk of developing dementia later in life.

Researchers took cerebrospinal fluid samples from the participants with mild cognitive impairment to look for underlying Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Twelve individuals tested positive. Participants also went through blood screenings to exclude “reversible causes of cognitive impairment.” These criteria included the presence of a major medical or psychiatric disorder, epilepsy, a history of excessive alcohol use or any visual or mobility impairment that would affect the ability to take a virtual reality test.

The Navigation Test

The research team hypothesized that entorhinal-cortex-based navigation would be impaired in individuals with pre-dementia Alzheimer’s disease. The team used immersive virtual reality, meaning participants actually walked around in a 3.5 by 3.5-meter space. Compare this to “desktop” virtual reality, which is performed sitting down. If the participants went outside the borders by just 30 centimeters, a warning sign became visible and they were encouraged to not walk any further. Researchers were there in the room as well to make sure participants did not go beyond the test space.

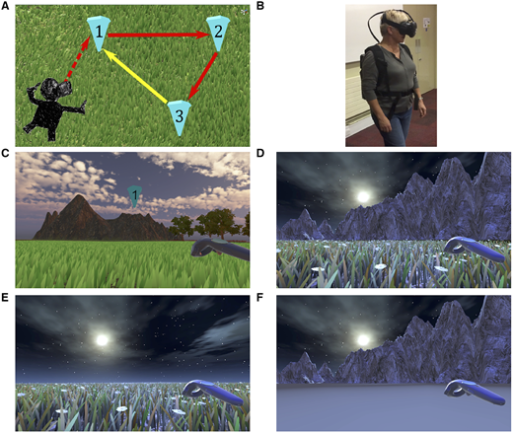

A) Illustration of the navigation task;

B) VR equipment;

C) Example of inverted cone location;

D-F) Return conditions; researchers would

remove environmental and surface boundaries

to test effects

Credit: academic.oup.com

The test itself was pretty rudimentary. Participants were instructed to walk in an L-shaped path to three different locations. Each location was numbered one, two and three by an inverted cone at head height.

Only one cone was visible at a time. The cone would disappear once the participant reached the location, and the next one would become visible. Once they got to the third cone, a visual message appeared asking them to walk back to their remembered site of the first cone. When the participant reached their estimated spot of that first cone, they pressed a button on a hand-held controller that logged the location and ended the trial.

The task consisted of nine trials within three different environments. Therefore, each participant performed 27 trials each. The environment was modified during the return paths to the remembered location of cone one. There were three return conditions utilized: 1) No environmental change (figure D in above image); 2) Removal of boundary clues (figure E above); and 3) Removal of surface details (figure F above). Each condition was presented three times per environment.

Results

The researchers found that patients with mild cognitive impairment did not perform as well on the task as healthy controls. Patients positive for Alzheimer’s biomarkers showed a larger propensity for errors than biomarker-negative patients. In fact, biomarker-negative patients with mild cognitive impairment did not perform significantly worse than the control participants.

Credit: agelab.mit.edu

Results also suggest that the virtual reality navigation task is more effective at differentiating between patients who are at high or low risk of developing future Alzheimer’s or dementia than the “gold standard” used for early diagnosis of the diseases.

“These results suggest a VR test of navigation may be better at identifying early Alzheimer’s disease than tests we use at present in [the] clinic and in research studies,” says Dr. Dennis Chan, lead author of the study.

Dr. Chan is confident that technology can play a role in diagnosing and monitoring Alzheimer’s disease/dementia. He is working with a technology professor at Cambridge to develop apps for detecting and monitoring Alzheimer’s. The apps would run on smartphones and watches.

Early detection is critical for mitigating symptoms and slowing or even halting the progression of the disease.

“We know that Alzheimer’s affects the brain long before symptoms become apparent,” says Dr. Chan. “We’re getting to the point where everyday tech can be used to spot the warning signs of the disease well before we become aware of them.”

Virtual Reality Could Help Diagnose Early Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

Virtual Reality Could Help Diagnose Early Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan