Bags of blood plasma

Credit: ctvnews.ca

Infusing blood plasma from young people into older adults to reverse symptoms of aging (such as dementia or heart disease) may seem a bit vampiric to some. Indeed, the idea of “young blood” producing anti-aging effects for elderly patients sounds like something from a science fiction or horror novel. However, it is currently a hot topic in the medical world that involves many moving parts.

The Food and Drug Administration recently addressed the practice, decrying the infusion of young blood plasma into aging persons as having “no proven clinical benefit.” The press release stated that, like the administration of any plasma product, there are inherent risks involved including infectious, allergic reactions and circulatory risks. The agency left the door open for clinical trials with regulatory oversight, however, stating that those are the only situations in which people should agree to the therapy.

The announcement comes at a time when young blood transfusions and their potential benefits have gained significant momentum in the medical community. In fact, a company called Ambrosia was recently offering the therapy to customers at a price of $8,000 for one liter of young blood, $12,000 for two. The brand ceased offering the service merely hours after the FDA’s statement.

According to Business Insider, the startup company only began its young-blood infusion program a few months ago. Its founder, Stanford Medical graduate Jesse Karmazin, lauded an Ambrosia clinical trial from 2017 involving the practice as “really positive.” The trial infused patients aged 35 and older with 1.5 liters of plasma from donors aged between 16 to 25 years over two days.

The participants’ blood was then tested for different biomarkers. Karmazin claimed that many people who received the young-blood transfusions noted benefits like renewed focus and improved memory, sleep and physical appearance. The results of the study were never published publicly.

Stanford Clinical Trial

A recent, small clinical trial from the Stanford Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences appears to suggest that young-blood plasma injections could improve functional ability in Alzheimer’s patients.

The study included 18 people aged 50 to 90 years old with mild to moderate symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The plasma used came from donors aged 18 to 30. The trial was meant primarily to test the “safety, tolerability and feasibility” of young-blood infusions in Alzheimer’s patients. The infusions proved to be safe.

Could young-blood infusions be a pseudo “fountain

of youth?” Credit: staugustine.com

The study was broken up into two separate stages. During the first phase, nine patients received young-blood plasma infusions while the other nine received a saline placebo. Patients and their caregivers were not told which they received. Following a wash-out period, the second phase gave the initial plasma recipients the placebo, and vice versa.

Patients were tested on mood, cognitive ability (memorize lists, recall recent events, etc.) and everyday functionality after the two rounds of infusions. Participants who received the plasma infusions and their caregivers reported improvement in everyday abilities like paying bills and taking medication, but their overall mood and cognitive functions did not improve.

The enhancement of patients’ functional abilities came as a surprise, according to lead author Sharon Sha, MD. Though encouraging, she notes that the small size of the trial and the point that improvements were self-reported and not scientifically quantified means that we should temper our excitement.

Parabiosis, Mice and Young Blood

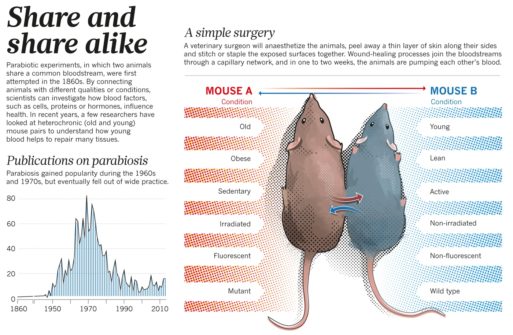

Infusing young blood plasma into the elderly for anti-aging potentials stemmed initially from a 150-year-old technique called parabiosis.

Parabiosis conjoins the circulatory systems of two living organisms to test the effects of a shared blood supply. Physiologist Paul Bert is credited with the first parabiosis experiment in 1864. He removed skin from the sides of two mice and sewed them together. Capillaries and wound-healing processes then took over, and the two mice shared a new circulatory system.

Parabiosis allows scientists to see what happens when the blood of one animal enters another. Experiments with parabiotic rodents were conducted in the 1950s and into the 70s, leading to breakthroughs in tumor biology and endocrinology, to name a few. However, tests largely stopped in the 70s.

Credit: nature.com

Parabiosis has had a resurgence in recent years. Scientists have discovered that joining the circulatory systems of young mice to older specimens seemed to revitalize the older ones. The blood of young mice appears to make older mice stronger, healthier and smarter, even contributing to shinier coats.

These positive findings do beg a few questions: Are these improvements a result simply of shared blood or that the two specimens share an entire circulatory system? Are the younger mouse’s organs doing the “heavy lifting” of cleaning and oxygenating the blood?

Tony Wyss-Coray, a neurologist at Stanford University, has performed parabiosis research on mice in the past. “I think it is rejuvenation,” he said in 2016 regarding the benefits seen in older mice due to parabiosis. “We are restarting the aging clock.”

Wyss-Coray co-authored a 2014 study that presented findings regarding cognitive, molecular and functional improvements in the brains of older mice that were exposed to young blood.

Benefits For Humans?

Young blood and its benefits are fascinating and appear to be quite effective in reversing aging in small rodents. The idea that young-blood plasma could reverse aging in humans is clearly in its infant stages and is quite a fractious issue.

That the FDA made a public announcement condemning the practice outside of clinical trials speaks to the importance of further research. Young blood seems to have the trappings of a “catch-all” kind of cure, with promises of everlasting youth.

It will be interesting to see what the results of further, more rigorous trials and studies with humans will have to show us.

For our readers in the San Francisco Bay Area, Tony Wyss-Coray will be in Palo Alto this Thursday, March 21 to discuss the newest research regarding young blood and aging.

Young Blood and Anti-Aging

Young Blood and Anti-Aging

“Hand to Earth” by Andy Goldsworthy

“Hand to Earth” by Andy Goldsworthy