Aid-in-dying laws in New Mexico are the most recent to stoke a discussion that will find itself in many state legislatures this year.

Credit: PBS Newshour

Terminally ill patients looking to choose when to die in New Mexico saw a welcome change this June. The Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act took effect on June 18 after the state legislature passed the act earlier this spring. New Mexico joins a growing contingent of nine states in the U.S. that added pathways for aid in dying since Oregon passed the Death with Dignity Act in 1997.

Such decisions are lauded by end-of-life advocates as a sign of progress and autonomy for patients struggling with painful terminal conditions. However, they are not always received with open arms.

In New Mexico, where hospital group Presbyterian Healthcare Services opted in to allow aid-in-dying procedures, Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, part of the Christus Health network of Catholic hospitals, told the Santa Fe New Mexican it would honor patients’ requests to decline treatment options by transferring them to a facility that allowed the procedure.

Catholic groups have been known to oppose aid-in-dying legislation. In 2015, The Sacramento Bee reported that the Catholic Conference and the Alliance of Catholic Health Care spent upwards of $200,000 a quarter on issues ranging from assisted death bills to sex education.

Some disability advocates see aid in dying as becoming too easy compared to life-sustaining measures. The Disability Rights and Education Fund noted in their 2019 report that “insurers have denied expensive, life-sustaining medical treatment but offered to subsidize lethal drugs, potentially leading patients toward hastening their own deaths.”

New Mexico, like California, also requires patients to administer the drugs themselves, and requires that the person be mentally competent in order to request the prescription.

Mental competency is often a sticking point for aid-in-dying laws. Alzheimer’s, even with recent potential breakthroughs, is always fatal, and patients are faced with a protracted end-of-life experience as faculties fade. As a result, by the time they have fewer than six months to live (as is required by all current aid-in-dying laws) they often do not possess what many medical professionals consider to be the mental capacity to qualify for the drugs.

These safeguards are, ideally, put in place to prevent a faster, legal process of ending one’s life prematurely. Still, a 2019 review of data of aid-in-dying recipients from Washington and Oregon published in JAMA Open Network showed that by and large the kind of folks getting access to end-of-life medication are those the law was intended to serve. Over the last 28 years, combined between the two states, over three-quarters (76.4%) of the 25,588 patients who died from lethal ingestion of medical aid-in-dying drugs cited cancer as their underlying illness, followed by neurological illnesses (10.2%), lung disease (5.6%) and heart disease (4.6%).

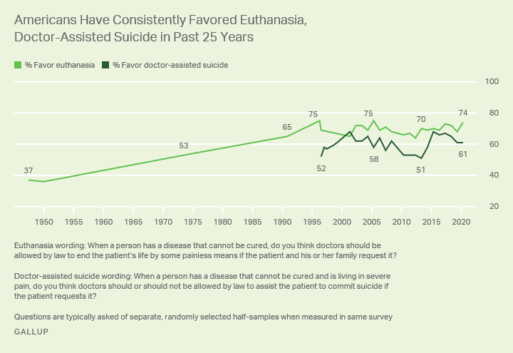

Credit: Gallup

Adjusting those barriers is a delicate tightrope to walk. Uniquely, Montana does not have an official law granting patients the right to access medical aid-in-dying. A 2009 State Supreme Court ruling allowed doctors to use patient consent for their defense in the event they’re charged with a crime in connection to an aid-in-dying procedure. Essentially for Montana doctors, any decision to supply drugs for lethal ingestion is taking a chance on a judge’s decision, greatly affecting the availability of medical professionals willing to grant patients’ aid-in-dying requests.

Canada Expands Aid-in-Dying Laws

That tightrope could be strung along the U.S–Canada border, where on the northern side, recent expansion of established aid-in-dying laws caused an uproar.

Changes in Canada’s medical aid-in-dying (MAID) laws were passed in March 2021, allowing those experiencing “intolerable suffering” who are not near the natural end of their lives to seek MAID immediately. The expansion also provides those whose suffering is caused solely by mental illness to gain access to MAID as of March 2023, according to reporting by the CBC.

The second provision is the most contentious among Canadian medical experts.

“It’s sacrificing marginalized people who have never had the autonomy to live with dignity to now choose death as a potential means of resolving their suffering,” said Dr. Sonu Gaind, a physician chair of Humber River Hospital’s MAID team and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, told the CBC.

Part of the issue lies with the breadth of services provided under Canada’s health system, critics say. Psychiatrist John Maher, M.D., criticized the plan in a February hearing with Canada’s Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Care, stating that, since universal palliative care, disability support or mental health care are not offered by the government, the dearth of options could cause people who could be otherwise treated to seek MAID.

Canada’s Justice Minister David Lametti told Al-Jazeera that restrictions are in place to prevent abuse. The patient has to be 18 or older, make the request voluntarily and be in an advanced state of irreversible decline that causes extreme suffering. As for availability to people suffering from mental illnesses, the government has two years to explore safeguards before 2023.

As state and federal governments navigate the law in practice, aid in dying has shifted from a radical proposition to a recurring note on lawmakers’ legislative calendar, with bills set to hit the Congressional floor of 13 states this year.

While accepted or under consideration in a slight minority among the states, the attitude around euthanasia has been relatively constant in the U.S. population. Current Gallup polls have public support for euthanasia at 74% just under the peak of 75% it hit in 1997 and 2005. Support for doctor-assisted death has gone down in recent years, dropping from 8 percentage points from 2015 (69%) to 2020 (61%).

Despite nearly a quarter-century of precedent, every state or country encounters a unique set of issues, stumbling blocks or unintended consequences as a result of their aid-in-dying legal framework. As lawmakers gain a greater understanding of aid in dying in practice, policies will be tweaked, lobbied for and against, and measured against one another. More decisions like New Mexico’s may be on the way, but not without intense scrutiny.

Expanded Aid-In-Dying Laws in North America Stir New (and Old) Debate

Expanded Aid-In-Dying Laws in North America Stir New (and Old) Debate

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento