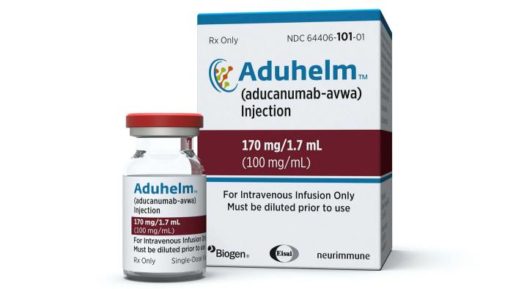

Aducanumab, or Aduhelm, is the first drug in nearly two decades to be approved by the FDA for Alzheimer’s disease.

Credit: WHSV3

One of the most confounding and debilitating diseases in medical science has a new treatment.

The Food and Drug Administration announced Monday, June 7, that aducanumab would be the first new medication for Alzheimer’s disease in 18 years. The decision comes as a beacon of hope for patients and caregivers but saddled with skepticism from the scientific community and the Food and Drug Administration’s independent advisory committee board.

How Will Aducanumab Work?

Aduhelm will be delivered as a monthly intravenous infusion intended to slow cognitive decline by targeting the amyloid plaques that build up in the brains of patients with mild cognitive impairment and early stages of Alzheimer’s. This is the first approved drug aimed at attacking disease pathology rather than managing symptoms of Alzheimer’s and MCI.

Nearly 6 million people in the U.S. and 30 million people globally have Alzheimer’s, a number that is expected to double by 2050. There are only five other approved treatments for Alzheimer’s in the U.S., all aimed at slowing cognitive decline in various stages of Alzheimer’s as well.

Who’s Behind It?

The drug was developed by Cambridge, Massachusetts-based pharmaceutical giant Biogen with the Japanese pharma company Eisai. It will go by the brand name Aduhelm and sell at $56,000 a year, not counting the costs for diagnostic testing and brain imaging to determine the need for treatment. Most patients won’t have to cover the full cost, as the drug is supposed to fall under Medicare part B, which covers many older Americans who would likely receive the treatment.

Biogen has spent years developing its Alzheimer’s drug. A cloud of previous trial failures and murky data has some experts concerned.

Credit: Wikipedia

How Did We Get Here?

Aducanumab traveled a rocky road to approval, one which has given some experts grounds for skepticism. Trials designed to show the effectiveness of the drug against cognitive decline over time were shuttered in March 2019 after they failed to produce convincing enough data. The failure of the aducanumab trials came at the end of a depressing trend of Alzheimer’s drug trial closures. Then in October of the same year, Biogen announced it would revive the trials based on long-term effects it was unable to track at the time of the closure. The company released the data that inspired the change in direction at an industry meeting in December 2019.

The presentation at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease Meeting had left attendees desiring more data but at least cautiously optimistic about the drug’s future and turning their sights toward the FDA, awaiting a ruling on the drug’s approval.

Aducanumab was then placed in the accelerated approval track, a pathway made for “earlier access to potentially valuable therapies for patients with serious diseases where there is an unmet need, and where there is an expectation of clinical benefit despite some residual uncertainty regarding that benefit,” according to the FDA.

What Are the Concerns?

In November, the independent review board for the FDA declined to endorse aducanumab over concerns about the drug’s effectiveness, departing from the FDA leadership’s optimism.

“In this case, I think they gave the product a pass,” Dr. Caleb Alexander, a medical researcher at Johns Hopkins University and a reviewer for the board, told the Associated Press after the drug was approved.

Other prominent Alzheimer’s researchers have expressed their concerns over the drug’s efficacy and the quality of the data revealed by Biogen.

Dr. Jason Karlawish, co-director of the Penn Memory Center, a trial site for aducanumab, wrote an opinion for STAT in May claiming he wouldn’t prescribe aducanumab even if it did gain approval.

Dr. Karlawish voiced his concerns over the drug’s cost and the data set supplied by Biogen.

“The data to make this case are murky and, even if they were clear, the drug’s benefits are ambiguous at best and not worth this cost. Putting it on the market will stress Medicare’s resources.”

Dr. Karlawish has also recently published a book on Alzheimer’s Disease, The Problem of Alzheimer’s: How Science, Culture, and Politics Turned a Rare Disease Into a Crisis and What We Can Do About It.

He also argued in a Q&A with the Philadelphia Inquirer that the measures in the accelerated approval focused on the drug’s ability to reduce amyloid in the brain rather than including “clinical measures such as how well patients were thinking or functioning in their daily lives.”

Patients and caregivers have been waiting for an innovation in Alzheimer’s treatment. Time will tell if Aduhelm is the answer they’re looking for.

What Now?

The FDA’s sign-off doesn’t come without caveats. Recognizing that Biogen’s data was insufficient, they required a Phase 4 trial to be conducted as a condition of approval. If aducanumab fails the Phase 4 trial, the FDA could revoke its approval.

“If the drug does not work as intended, we can take steps to remove it from the market. But hopefully, we will see further evidence of benefit in the clinical trial and as greater numbers of people receive Aduhelm,” the FDA announced in its press release.

The FDA’s record for pulling drugs for failing trials is inconsistent. In 2011 the FDA pulled a breast cancer drug approved through the accelerated track after studies showed that “there was not, at the time of approval, credible evidence of increased overall survival or increased quality of life, and there is no such evidence now.”

However, the administration has been known to let cancer drugs slide even after the drugs fail follow-up trials.

Biogen aims to complete the follow-up trial by 2030, the AP reports. Meanwhile, the company has seen its shares rise 38% and its valuation soar to $60.1 billion as of Tuesday, June 8, a $16 billion leap from the previous week.

The FDA-issued label for Biogen is much wider than the population tested in the trials, which consisted of people with higher-than-normal levels of amyloid in their brains. The label allows for use generally “in the treatment of Alzheimer’s.” This is an important distinction, as not all patients with Alzheimer’s or cognitive impairment have higher amyloid levels, leaving prescription up to specialists’ discretion. Biogen plans to start shipping millions of doses within the next two weeks.

Patient advocacy groups like the Alzheimer’s Association see this as the end of a path riddled with obstacles ultimately yielding a rare piece of positive news for patients.

“[This is] an exciting era in Alzheimer’s and dementia treatment and research,” the Alzheimer’s Association stated on its website. “It’s a new day in the fight to end Alzheimer’s.”

The emotions range from caution, sighs of relief, and elation in patients and caregivers as they finally gain some kind of ground in the long uphill battle that Alzheimer’s and dementia present.

“I think it will reopen, and reinvigorate, reenergize the medical community and bio-pharm world to delve even further to try to find a better treatment and cure for Alzheimer’s,” said Phil Gutis, a participant in the aducanumab trials, in an interview with WPVI-TV Philadelphia.

FDA Approves New Alzheimer’s Drug Amid Expert Skepticism

FDA Approves New Alzheimer’s Drug Amid Expert Skepticism

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition