A new study out of Stanford University suggests that patients should share a “bucket list” (if they have one) with their physician to facilitate better “preference-sensitive” care. With this strategy, researchers contend that doctors can make more suitable healthcare recommendations because they know their patient’s life goals.

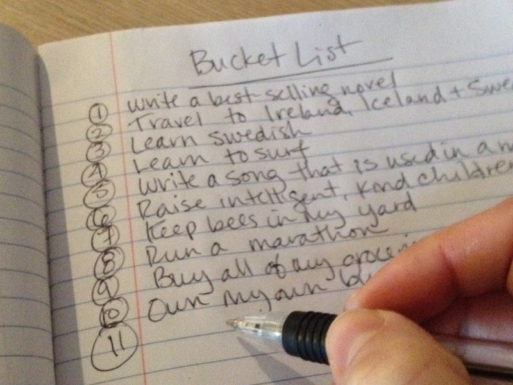

A bucket list is essentially a list of things that a person would like to accomplish before they die. Common “items” on a bucket list include traveling to certain places, learning a skill, accomplishing a specific goal or reaching a personal milestone.

Credit: onmilwaukee..com

Bucket lists can be beneficial for many reasons. They are an acknowledgment of our mortality and the fragile nature of life. A bucket list can help people to hone in on the things that are important to them. Developing a list of accomplishments that we’d like to achieve or places we want to visit can jump start a life of meaning and encourage us to really take advantage of the time we have.

We can also use a bucket list to reflect on what’s vital to leading a fulfilling life, encompassing an array of beliefs, desires and goals.

According to the study, published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine, physicians can make better-informed decisions regarding a person’s potential treatment plan if they know the contents of said person’s bucket list. If doctors knows what patients want to accomplish, they can recommend treatments that would be less likely to interfere with a person’s goals. At the very least, physicians can discuss the positives and negatives of each potential plan related to the patient’s bucket list.

For example, the researchers provide a short anecdote about a man who had an advanced form of cholangiocarcinoma. A vital life goal of his was to take his family on a trip to Hawaii before he died. After a detailed conversation with his doctor about possible treatments and their side effects, the man chose to delay treatment until after he returned from the trip. In this instance, delaying treatment enabled the man to check that item off his bucket list.

Researchers not only studied the possible benefits of sharing a bucket list with a physician. The study also identified and ranked which “wishes” were most common among the participants.

Study Results

The researchers surveyed more than 3,000 people across the country asking if they had a bucket list and what was on it. The participants then ranked their desires in order of importance. The average participant was 50 years old.

The most common desire was a wish to travel, listed by more than 78 percent of the respondents. A desire to fulfill a personal goal came in second; achieving a specific life milestone was third; and spending more time with family and friends was the fourth most-common desire. Financial stability and taking part in a daring/risky activity (sky diving, bungee jumping, etc.) were the final two most-commonly recurring themes.

The study mentions how it’s a well-known practice for physicians to discuss goals of care with their patients. However, they note that many times these conversations are not as beneficial as they could be. Most patients are not health-savvy enough to fully understand the ramifications of differing treatment plans.

Traveling is a common theme on bucket lists

“Many patients,” the researchers write, “who do not have the health literacy to truly comprehend the impact of their medical decisions on their lives and their family may prematurely choose certain treatment options only to change their mind later when they start feeling the real impact of these choices on their life. We propose the use of the bucket list to help patients identify what matters most to them.”

If physicians know what their patients want out of life, they can fine-tune discussions to be more aligned with each person’s bucket list. The care plan will therefore aid in establishing a better quality of life during treatment.

In Tandem With Advanced Directives

The researchers’ push for bucket-list discussions stems in part from the fact that end-of-life planning is currently very “document-oriented.”

“If we look at advance directives as the savior of our health system, it’s not going to work,” said study author VJ Periyakoli, director of the Stanford Palliative Care Education and Training Program in California. “I don’t want to wait for my doctor to tell me it’s time to do my advance directive. I would rather go to the doctor and say what’s on my bucket list.”

A discussion about a bucket list is much more personal and intimate. Conversations about advanced directives are often business-like and come across as solely about dying.

“Advance directives are about death; a bucket list is about living,” said Susan Mathews, bioethicist, nurse and instructor at Indian River State College in Florida. “A bucket list, if prepared with a dose of serious reflection, gets to the heart of our relationship with self and the others for whom we care.”

This is not to say people should stop filling out advance directives; they’re still necessary. But it is intriguing to think about the ways in which a bucket list can facilitate treatment plans regarding illness and/or end of life.

A “Bucket List” May Be Beneficial For End-Of-Life Treatment

A “Bucket List” May Be Beneficial For End-Of-Life Treatment

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States