Dan Diaz discusses medical aid in dying on the steps of the state Capitol in Sacramento, California, in 2015.

Like any chapter in our lives, the end can bring blessings as well as challenges. Sometimes we gain clarity as we look back on the past; we may draw closer to family, regain lost connections, or realize dreams we’ve deferred. But it’s an undeniable truth that for some of us, the end of life can bring suffering — a fact that is sometimes as difficult to face as death itself.

In 2020, we talk about death. Maybe not often, maybe not eagerly, but the conversation around the ultimate taboo is beginning to take a more familiar place in our lives. Still, these conversations tend to focus on the positive or inspirational aspects of age and dying: the cancer patient who discovers her true passion, the grandmother offering wisdom, the terminally ill child who sees his wish granted. These are important stories, but they reveal our collective hesitation to address the full reality of physical and mental decline.

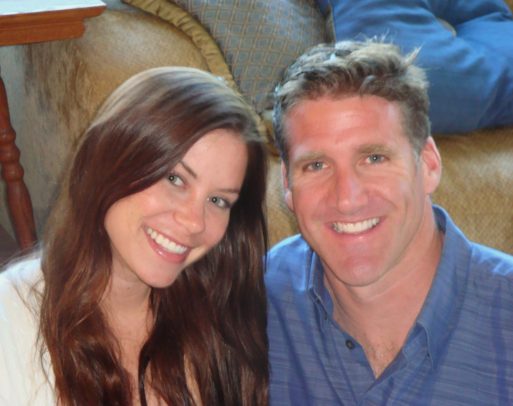

Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old schoolteacher living in California, faced this reality when she was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer in 2014. The remaining months of her life looked grim: seizures, nausea, sleepless nights spent fighting pain. Worst of all, she would suffer through these increasingly brutal days with no hope of respite or recovery.

After extensive research and several conversations with her doctors, Maynard decided to obtain a prescription for medical aid in dying. That way, if her symptoms became unbearable, she could safely end her own life. Even if she never took the medication, she would regain some control over how her final days played out.

At the time, however, MAID wasn’t legal in California. Maynard and her husband, Dan Diaz, decided to move to Oregon so she could establish residency and obtain the prescription there. The experience spurred Maynard to speak out about the issue, advocating for legalization so that patients like her wouldn’t have to uproot their lives to get access. “If we’re across some imaginary line on some map, and we’re standing on Oregon soil — there, she had the option to make sure her dying process was gentle,” said Diaz. “But if we take a step back into the California side and we’re standing on California dirt, all of the sudden, now she has to roll the dice and has to endure what that brain tumor was going to do to her.”

Brittany Maynard with her husband, Dan Diaz

Maynard made the decision to take her medication in 2014. Since then, 10 states have adopted MAID laws, as well as Washington, D.C. This is a dramatic increase from just Oregon, Vermont, and Washington in 2014, and it appears that trend continues, as several states have pending legislation to enact similar laws.

In the places where MAID is legal, there’s no denying that the service is easier to obtain than it once was — a change that many credit to Maynard, whose story shifted the public’s perception. Twenty-two percent of Americans now live in states with “death with dignity” laws. But that doesn’t necessarily mean their path to MAID will be any easier than Maynard’s. For many terminal patients living in the states that allow MAID, legal is not the same as accessible.

Acceptance is Growing — But Stigma Still Lingers

While acceptance of MAID is on the rise in the general population, it remains a deeply emotional issue for those who oppose it. Many hospitals fear stirring up controversy, and since participation is optional, the facilities that do choose to offer MAID can be few and far between. Some hospitals are also forbidden from participating because of religious affiliations; the Catholic Church, which funds many medical facilities, is a staunch opponent of the right-to-die movement.

While acceptance of MAID is on the rise in the general population, it remains a deeply emotional issue for those who oppose it. Many hospitals fear stirring up controversy, and since participation is optional, the facilities that do choose to offer MAID can be few and far between. Some hospitals are also forbidden from participating because of religious affiliations; the Catholic Church, which funds many medical facilities, is a staunch opponent of the right-to-die movement.

However, some doctors also choose to opt out due to personal beliefs. Support for MAID is lower in the medical community than in the general population, and some physicians cite concerns about its implications for abuse or claim that it conflicts with their medical ethos. The American Medical Association voted to reaffirm its opposition to MAID in 2019, while many smaller medical associations, such as the American Public Health Association and the American Medical Women’s Association, are in favor of it. Around six out of ten doctors support the option.

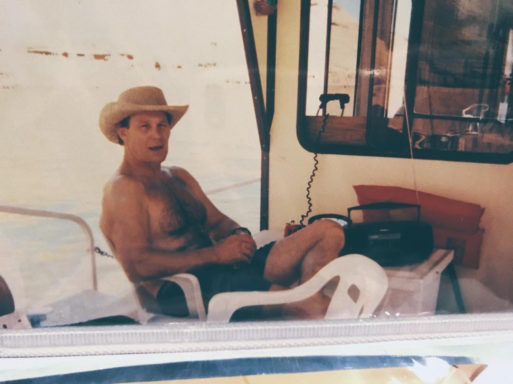

Supporting an idea, however, is not the same as making it easy. When Nathan Whittington, a prominent science teacher with terminal brain cancer, decided to apply for MAID in his home state of California, his daughter Shamara offered to help him through the application process so that he could focus on enjoying his life. A scientist herself, Shamara was no stranger to extensive research, but she found herself confronting a string of dead ends when it came to locating resources. When she contacted local hospitals to ask if they participated, “everything stopped at the receptionist,” she said. “The minute you say ‘end of life options,’ people clam up.”

Nathan Whittington in 1994

Unlike dermatologists, heart surgeons, lung specialists, and almost every other type of physician, doctors who participate in MAID don’t always advertise their services. There is no directory or catalog to guide a patient’s search. Finding a doctor who will participate can lead to a process of trial and error. But those who need assistance in locating someone in their immediate area can contact The American Clinicians Academy on Medical Aid in Dying for a potential referral.

Shamara finally learned from an acquaintance about a facility in the Bay Area, which in turn directed her to Dr. Patrick Macmillan in Fresno. Even once there was a medical team on board, however, she had to constantly push the approval process forward. The doctors seemed reluctant to describe each next step. “They moved along only because we forced the issue,” Shamara said.

Looking back, she said, there was “no way” her father could have made it through the application process without help. From discovering the option in the first place to filling the prescription, each step required a level of energy and persistence that few people possess at the end of their lives. Without a loved one like Shamara “who’s sitting up at three in the morning, going ‘you know what, this is legal in Oregon …’” many people in her father’s position would never even have known that MAID was available to them.

Nathan Whittington with his daughter, Shamara

Same State, Different Worlds

The struggle that Shamara experienced is not uncommon among MAID patients and their families. Linda Estes remembers running into “roadblock after roadblock” when she helped her father obtain MAID in Washington. The process had been legal there since 2009, but they were living in an area where the local hospital and pharmacy were not equipped to participate.

Their doctor was willing to help, but his employer forbade him from doing so. It was only with persistent effort that Estes was able to help her father obtain all the resources he needed to apply for and obtain a prescription.

“I said to myself after that, ‘It should not matter what zip code you’re in. It’s legal in the state, it should be accessible in the state.’” Estes started volunteering, raising awareness and convincing her local hospital to participate. Eventually, she began working as the Community Engagement Coordinator for End of Life Washington, a nonprofit that provides information and support for those seeking MAID.

Through EOLWA, Estes has worked with patients across the state, some of whom live in rural communities with no internet access. While physicians will occasionally conduct MAID assessments over the phone, having to travel to in-person appointments or to pick up the prescription can be a problem for older and physically compromised patients.

Geography can be a major limiting factor for prospective MAID patients — not just in terms of distance, but also in terms of culture. In states where MAID laws have been passed, acceptance of the law is not universal. In Colorado, there are cities and precincts where the law passed with a 70 to 80% of the vote, said Dr. Jeremy Long of Denver Health; in other parts of the state, however — primarily rural and conservative areas — that percentage flips. “We have had some patients really have to fight through some of those barriers and overcome stigma to seek us out,” Long said.

When it comes to end of life options, cultural norms and expectations can be as limiting as a lack of resources. Both issues relate to stigma, and both can hinder a patient’s access to medical aid in dying. Ultimately, that means the people who can and choose to receive MAID tend to occupy a very narrow range of demographics.

The majority of patients who obtain medical aid in dying are well-educated, have access to high-quality health care and insurance, and are enrolled in hospice. While little data exists on the economic backgrounds of MAID patients, a prescription can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars without insurance — a price that could be prohibitive for patients with limited funds.

MAID patients are also predominantly white. The only states with MAID laws were once majority white population, but that has changed in the past several years. These laws have spread to more diverse regions, but annual reports show that the demographics of MAID patients have yet to reflect that diversity.

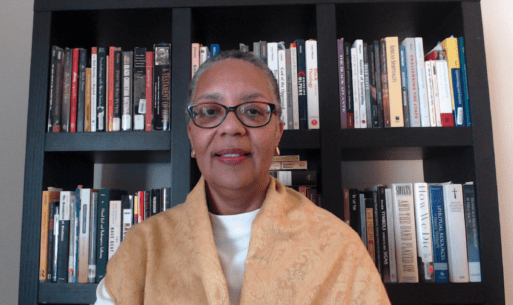

As with many medical issues, the discussion around MAID too often centers on a middle-class, white experience. Some experts point out that the controversy around MAID distracts from other problems with end-of-life care. This is particularly relevant when it comes to racial inequity. To Terri Laws, Ph.D. a professor of African and African American studies and religious studies at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, the question that must be addressed is, “How does medical aid in dying promote justice?”

“Black people and other people of color often do not experience official processes in the same way as whites,” Laws said. “Systemic neglect, individual dismissal, under-valuing, stereotyping — any of these sociocultural aspects of the physician-patient (and family) interaction can contribute to difficult or disparate outcomes for Black people.”

Those who are seriously ill find it hard to

find a doctor who will help them

through the process, even when they

qualify for aid in dying.

Team Adem on Facebook

Negative health outcomes occur at a strikingly disproportionate rate for Black and Indigenous patients and people of color, a fact that has been largely ignored by the healthcare system despite being freshly illuminated in the COVID-19 pandemic. This, along with the American medical system’s history of exploitation and inequity, often impacts the trust that a patient is able to place in the healthcare industry.

Given this relationship, the decision to pursue MAID may be significantly more complex for someone who isn’t white — or, for that matter, someone who isn’t straight or cisgender. While no data currently exists on LGBTQ patients and MAID, general statistics on healthcare access reflect rampant discrimination. Ultimately, accessibility in MAID is tied to the much larger issue of accessibility within the healthcare system as a whole.

Family Attitudes Can Influence Decisions

It isn’t just societal culture that affects a patient’s decision to pursue MAID; family culture can be a powerful factor as well. A patient’s loved ones may disapprove of the option for a number of reasons — religious beliefs, misconceptions fueled by stigma, or reluctance to face the reality of the patient’s death. These reactions can range from apprehension and anxiety to anger and fear, and they can be a powerful deterrent for patients considering MAID. After all, few would consider a rift in the family to be ideal conditions for leaving this world.

Some hospitals, like Denver Health, offer support for family members going through the MAID process. Dr. Long recalls a MAID candidate who had one Catholic daughter and one Protestant daughter; the two were at odds over their mother’s end-of-life decision. The staff at Denver Health were able to work with the family and encourage the patient’s daughters to accept their mother’s wishes.

Resolving such conflicts, said Long, is not about getting family members to change their own feelings. It’s about helping them to honor their loved one’s decision — even if it isn’t the one they would make.

For family members who are able to accept the decision, there are still some complex emotions to navigate. In his work with MAID patients and their loved ones, Long has often encountered something called “complicated bereavement”; families feel relief and happiness for their loved one when the prescription is obtained, but that relief is complicated by their own grief.

While some MAID candidates struggle to align loved ones with their decision, however, others suffer from the lack of any support system. This can lead to both emotional and logistical challenges in the MAID process. These patients may struggle to find rides to the doctor’s office, for instance, or to fill out paperwork without assistance. While help is sometimes available from volunteer organizations, it is difficult to find a substitute for intimate human connection at one of the most vulnerable times of one’s life.

Eligibility Can Be Fleeting

While MAID laws can vary from state to state, certain eligibility requirements are always the same: Qualifying patients must be mentally competent, have six months or less to live, and be physically able to self-administer the medication.

On the surface, these seem like reasonable stipulations for such a weighty decision. In reality, however, it can be difficult for a patient to meet these requirements — and prove it — at the end of life.

Nathan Whittington, for instance, was still perfectly coherent by the time he was able to schedule a mental evaluation. Still, Shamara remembers the assessment being challenging. At one point, Whittington was asked how tall he was and answered, “Eight feet tall.” While his mental faculties were still largely unaffected by the disease, he’d lost his awareness of numbers. In order to truly get an accurate picture of someone’s mental capacity, Shamara said, “you have to be so broad in your questioning.”

Although Whittington did pass the assessment and qualify for the prescription, the grey areas of mental evaluation can mean that some patients fall through the cracks. What’s more, depending on how long the whole process takes, a patient who is perfectly sound of mind when they decide to seek MAID may have deteriorated by the time they can be assessed. “I’ve had patients who want the end-of-life option, but they do it so late in the game … they lose the capacity to make the decision,” said Dr. Patrick Macmillan, Whittington’s consulting physician.

From the first request to the actual prescription, the entire process can take as little as 15 days in some states, but this is rarely the case. All applicants must first be evaluated independently by two different physicians. If the patient is deemed eligible, he or she must submit a series of requests separated by waiting periods. Those waiting periods can be several days to several weeks, dependent upon which state you live.

Nathan Whittington was able to qualify for medical aid in dying before brain cancer symptoms affected his eligibility.

For anyone with a debilitating illness, that sort of time span can bring a lot of changes. By the time a patient receives a prognosis of six months or less, the disease is already well into its advanced stages; in some cases, that can mean severe impairment — and rapid deterioration. It can be a matter of months, weeks, or days before the physical and mental faculties that make a patient eligible begin to erode.

Many progressive diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, rob patients of their physical and mental faculties years before they would receive a six-month prognosis. Since medical aid in dying cannot be included in advance directives, this effectively rules out MAID for many who suffer from the very diseases that most impact quality of life.

Digestive conditions like pancreatic cancer can also affect a patient’s chances of approval. After all, if the medicine can’t be digested properly, it won’t work. The U.S. is unique among countries that have legalized MAID in that it does not permit intravenous delivery: The prescription is generally taken orally, and it must be administered by the patients themselves. In some instances, patients may have an ability to self-administer those via nasogastric or rectal tube when warranted. However, Dr. Parrot believes that allowing intravenous delivery would only intensify the stigma around MAID — making it even less accessible.

The Fight Continues

Those who advocate for end-of-life options are well aware that the battle is far from won. That’s why many organizations and individuals are working not only to enact death with dignity laws across the U.S. but also to address the barriers that still keep so many patients from having access to medical aid in dying.

Groups like End of Life Washington, Compassion and Choices, and the Death with Dignity National Center work with hospitals and patients within their states to provide information, support and advocacy for those seeking MAID. This February marked the first National Clinicians Conference on Medical Aid in Dying, in which doctors, counselors, and scientists from across the country came together to share information and perspectives.

End of Life Washington

volunteer Chris Fruitrich has

helped 200 patients die.

Some organizations also train volunteers to help MAID candidates through the process. Chris Fruitrich, a volunteer with End of Life Washington, has counseled around 200 patients over the past seven years. While volunteers don’t always have medical backgrounds, said Fruitrich, they are extensively trained in every aspect of the process so that they can provide guidance and answer questions for patients and their families — something physicians don’t always have time for outside of scheduled appointments.

Many of the people behind these efforts started advocating for end-of-life options after seeing the peace it gave to their own loved ones — or seeing others suffer without it. When Chris Fruitrich started volunteering with EOLWA to counsel patients through the MAID process, he had watched two friends suffer through painful terminal cancers, one in a for-profit hospice. While he can’t say whether they would have chosen MAID, the experience compounded his belief that “people in those circumstances should have a choice,” he said. “You should have the option of deciding when you want to die, not be at the mercy of a disease.”

Shamara Whittington became a vocal advocate for MAID options after witnessing the relief it granted her father, Nathan. He’d watched his own father suffer from Alzheimer’s, and he’d always said that he didn’t care what happened to him as long as it didn’t affect his mind. After he was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, MAID freed him from spending his remaining days dreading that inevitable decline. His dying wish was that Shamara work with his doctor, Patrick Macmillan, to raise awareness of end-of-life options.

Physicians often become involved with MAID for similar reasons. Some, like Macmillan and Long, began educating themselves on MAID after it became legal in their state and patients started to ask them about it. “It enriches me and my humanism to think about anyone being able to avail themselves of what they need as they face their end of life,” Long said, “and think about what we can do to be of most service.”

MAID isn’t just about dying peacefully, however. It’s about living peacefully. Many terminally ill patients feel an immense sense of relief in simply obtaining the prescription, knowing that they have some control over what lies ahead. “When that prescription hits the pharmacy, it’s almost like they got a shot of adrenaline,” said Chris Fruitrich. “Because the disease is no longer in control of when they’re going to die.” Dan Diaz, Brittany Maynard’s husband, saw the peace it gave her to know she could die on her own terms: “She put the medication in the cupboard, and her focus was on doing the things that mattered to her.”

Nathan Whittington with his granddaughter, Josslyn

Without the uncertainty and dread of an agonizing decline looming over them, MAID patients can devote their energy to enjoying the time they have left. Shamara Whittington remembers the final days before her father took his prescription: “I could feed him crab legs. He taught me to drive his old car that he’d never taught me how to drive.” He was grateful to spend his remaining time at peace and surrounded by people he loved. He had “absolutely everything that he wanted,” she said. “There’s nothing more that anybody could ask for.”

For more information on medical aid in dying or to request a doctor referral, visit the American Clinicians Academy on Medical Aid in Dying website.

Medical Aid in Dying: Legal but Not Always Accessible

Medical Aid in Dying: Legal but Not Always Accessible

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville