Credit: Base64, retouched by CarolSpears

Back in 2009, hedge fund founder Jim Chanos was convinced that China was in the midst of a major economic bubble. Over the preceding decade, the country had invested in billions of square feet of land, building brand new cities between urban hubs and rural countrysides. It was also accumulating mountains of debt. Chanos predicted that China’s speculative economy would soon crash, and he was correct. Today, the country’s economy is in a free-fall that is impacting investors all over the world.

While financial advisers worry over future stocks in Chinese companies, families in China have a more pressing concern: widespread grave relocation. Due in large part to the country’s real estate boom, the Chinese government has expanded development into established gravesites, replacing buried bodies with infrastructure designed for homes and businesses. As a result, families are being forced to relocate their dead loved ones, often with few or no alternatives. About 15 million bodies have already been relocated in response to the increased demand for land.

About 15 million bodies have already been relocated in response to the increased demand for land.

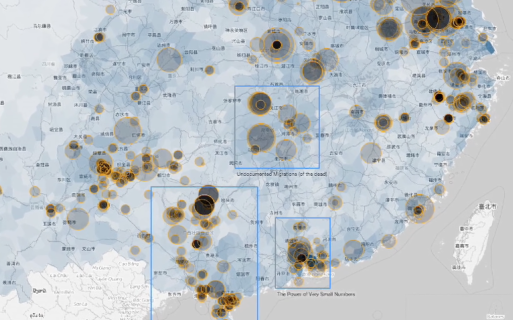

Recently, Stanford scholar Tom Mullaney formed the Grave Reform in Modern China project, which uses digital tools to track each of these relocations. The hope is that the tool will show the human impact that China’s grave-relocation project has had on the people involved, partly through stories and partly through hard data.

Dingding Mao performs the wailing portion of the traditional funeral ritual

(Credit: NPR)

The project uses two points to focus the project: First, users can look at a map of China and see where grave relocations are taking place and why the government decided it was the best course of action. Next to the data, they see personal essays and stories from families whose dead loved ones were relocated and how it affected them. For example, users can view the relocated grave of a World War II veteran and also read about the impact that the move had on the veteran’s grandchildren today.

The problem lies in the aftermath, when families are forced to cope not only with their loved ones being physically removed from their graves, but also with the difficulty of visiting them in a brand new location.

When large-scale development takes place, it’s difficult to fully express the human impact these decisions have. For Chinese developers, the choice between moving a gravesite and building a new city is an easy one; body relocation is relatively cheap and easy to work around. The problem lies in the aftermath, when families are forced to cope not only with their loved ones being physically removed from their graves, but also with the difficulty of visiting them in a brand new location. For rural families, who often have little money or resources, even a 20-mile move can make it impossible to visit loved ones’ graves.

In some circumstances, the dead are not even reburied.

In some circumstances, the dead are not even reburied. The Chinese government informs surviving family members of an impending grave move, usually by mail. The family must confirm that they understand that the grave will be moved and consent to a reburial. If the family does not respond, or the government has no record of surviving family members, the remains are removed from the gravesite, cremated and then disposed.

In addition, even when a body is reburied by the government, there is no guarantee that it will be buried in the same way that it was buried initially. In most cases, the family is not involved in the process at all, and are deprived of the right to participate or have their beliefs, rites and traditions honored when the reburial takes place.

Grave relocation is in many ways inevitable in China, given the population crisis and the demand for land and more places to live. As time goes on we will likely see many more graves moved, and fewer options for those impacted by these moves.

The Chinese government is already encouraging many of its citizens to forgo burials entirely, pushing for more cremations to save space. As a result, Chinese funeral rites are rapidly changing, doing away with centuries-old traditions in favor of those that make the most economic sense. Grave relocation may be just the tip of the iceberg.

Relocating China’s Dead

Relocating China’s Dead

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento