We hear a great deal today about elder abuse, including physical, emotional and financial abuse. The National Council on Aging reports that an estimated one in 10 people over the age of 60 have suffered some form of abuse, and that number is far higher for those with physical disabilities or dementia. And though all states in the U.S. have mandatory reporting laws, only one in 14 cases of elder abuse are actually reported, according to the National Research Council’s study “Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation in an Aging America.”

Social isolation and poverty contribute to self-neglect

But while abuse by others is by far the most recognized form of elder abuse, there is another kind of elder abuse of which the public is largely unaware — intentional self-neglect. And it’s not a rare occurrence. According to a recent report in the N.Y. Times, adult protective services agencies nationwide received more calls about elderly persons harming themselves through neglect and lack of self-care than any other kind of call.

Take the case of an 86-year-old man who lived alone with his two dogs in a remote part of Texas. A Vietnam veteran, he suffered from diabetes and chronic cellulitis but had adequate supplies of medication to treat both conditions in his home. He also had a working toilet, running water, electricity, and, because walking was painful, a scooter he used to move around the house.

But when an APS worker — alerted to a possible case of elder abuse by a neighbor — visited the man’s home, she found him living in filth. He did not clean up after his dogs. And rather than use the toilet, he urinated in empty gallon jugs, which were strewn around the house. He was poorly nourished, was not taking his medications and, based on the number of empty liquor bottles littering the home, appeared to be abusing alcohol. But when the worker offered him assistance, he refused.

Autonomy at All Costs?

Here in America, we highly value autonomy — one reason why family and friends often turn a blind eye to self-neglect. We believe on a fundamental level that people with the capacity to make their own decisions have the right to live as they choose, even if that means living in filth and engaging in behaviors that jeopardize their health. “As a society, we want to respect autonomy and independence,” said Dr. XinQi Dong, a researcher at the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging in Chicago.

Hoarding is often an indicator of self-neglect

Credit: rightathome.net

Further, self-neglect is often hidden from mandatory reporters such as physicians, nurses and social workers. If a patient shows up for his medical appointments and appears clean and neat, there’s little reason for providers to suspect that something’s wrong. Yet that person may well live in squalid conditions, fail to take prescribed medications or endanger their well being in many other ways.

“People can have sores or lice or pests in the house,” said Courtney Reynolds, a research analyst at the Benjamin Rose Institute on Aging in Cleveland, in a statement to the NY Times. “There could be piles of garbage, or food stored in a refrigerator that’s not working,” she adds. Hoarding of personal possessions, trash and/or pets is also common, according to Dr. Dong. Social isolation exacerbates the problem, he said.

Even when family and other support systems are available, however, there’s a reluctance on the part of others to report what’s going on. According to Raymond Kirsch, an investigator who worked on a Vietnam vet’s case, involving the authorities triggers fears of “Big Brother” stepping in and dragging the loved one off. “But that idea of us kicking in doors and hauling people out to nursing homes is so wrong,” he said. “Our goal is to keep people in their homes as long as humanly possible — but safely.”

A Growing Concern

As our population ages and more elderly people live alone, the problem of self-neglect is likely to get much worse. Even today, Dr. Dong’s research indicates that it is shockingly common. In one study involving 4,600 Chicagoans over the age of 65, researchers found that between 9 and 10 percent of men and 7.5 to 8 percent of women were victims of self-neglect. And, because many people refused access to their homes, “it wouldn’t surprise me if the numbers were higher,” Dr. Dong said.

Self-neglect is more common when the person suffers from poor physical health, impaired cognitive function, and/or mental health issues, according to a study by Dr. Dong and colleagues published in the Journal of Aging and Health. Depression and cognitive impairment, in particular, were predictive of self-neglect.

A System Whose Hands Are Tied

And yet, all too often, there is little that family, friends or the system can do, even after they become involved. The Texas veteran who was living in squalor, for example, eventually allowed social services to get involved in his care. Kirsch assigned a home health aid to visit the man regularly, had the house professionally cleaned, and arranged Meals on Wheels. Yet, one month later when a caseworker visited his home, the man had deteriorated to the point where he was quite ill and his mental status was significantly impaired. He was taken to the emergency room and, after a judge determined he was no longer competent to make decisions for himself, admitted to the hospital.

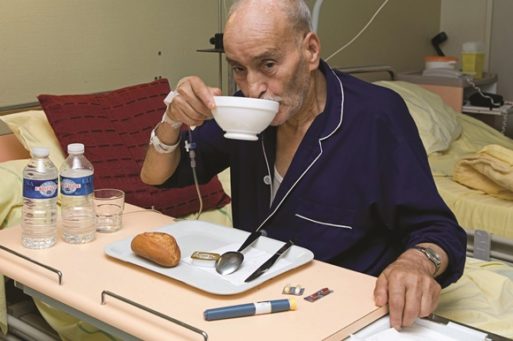

Good care can reverse some of the effects of self-neglect. But what then?

Credit: pharmaceutical-journal.com

After a month of abstinence from alcohol, good nursing care and healthy food, the man had improved remarkably, said Kirsch. In fact, he looked so healthy that a judge and his physician decided that he was once again mentally competent to manage his own care. And what he wanted to do was go home.

Kirsch was present when the man returned to his home and his dogs — and a cupboard fully stocked with booze. Then the man sent him on his way, telling him he wanted no further help.

“My heart sank” Kirsh said. “You know it’s not going to get better.” But there was nothing more the agency could do.”

Searching for Solutions

Even researchers like Dr. Dong admit that the answers to elder self-neglect are hardly clear. In some states, self-neglect is not even investigated by social services. And even in places where it is, caseworkers are so overworked and solutions so nebulous that many people simply fall through the cracks.

But there’s no denying something needs to be done. People who suffer from self-neglect are more likely to be depressed and are at greater risk of poor health outcomes than others in their age group, according to a study published in JAMA in 2009. They are also at a higher overall risk of death.

Later this month, the American Society on Aging will be discussing the issue of self-neglect and possible solutions at its “Aging in America” Conference. But until clear policy decisions are made and a framework is in place, recognizing and reporting suspected self-neglect are still important first steps.

Not sure what to look for? The National Adult Protective Services Association provides this list of indicators that a person you know may be engaging self-neglect.

- Inadequate heating, plumbing or electrical service disconnected

- Pathways unclear due to large amounts of clutter

- Animal feces in home

- Residence is extremely dirty, filled with garbage, or very poorly maintained

- Not cashing monthly checks

- Needing medical care, but not seeking or refusing it

- Lacking fresh food, possessing only spoiled food, or not eating

- Refusing to allow visitors into residence

- Giving away money inappropriately

- Dressing inappropriately for existing weather conditions

Self-Neglect — A Poorly Recognized Form of Elder Abuse

Self-Neglect — A Poorly Recognized Form of Elder Abuse

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

“Comeback” by Prince

“Comeback” by Prince