Credit: bizarro.com

According to an article published by The Nation this past summer, approximately 28 million uninsured Americans face the prospect of dying painfully, without the medication or other social supports accessible to those who have health insurance. Primarily made up of working-poor adults under 65 years of age and the 11 million undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers for whom contact with any part of the healthcare system may mean deportation to their home country, these people are part of America’s growing healthcare “coverage gap.”

Credit: angelsinhome.com

Medicaid is a government-funded insurance program designed to provide coverage for Americans who cannot afford private insurance and do not qualify for Medicare. However, despite increased Medicaid funding made possible under the Affordable Care Act, in many parts of the country it is nearly impossible for adult individuals to qualify for Medicaid if they are not pregnant, a parent on welfare, elderly or disabled. What’s more, many of these people are low-wage workers who also don’t qualify for subsidies under the ACA. (In order to qualify for subsidies, the household income must be at least $20,000 per year for a family of three.) Of those who might qualify, many are paid in cash, which makes documentation of income difficult to obtain. Because these people can’t afford health insurance without a federal subsidy, they and their families remain uninsured.

Some communities, such as Harris County, Texas, provide an alternative option for undocumented immigrants, but providing documentation of income and place of residence remains a challenge for many who are otherwise eligible for the support.

In the U.S., very few people of color can afford hospice care as they approach the end of life

(Credit: stockbyte.biz)

Presently, more than 76 percent of hospice patients in America are of European descent and/or have light-skinned privilege. By contrast, about 5 percent of individuals in poor urban communities — often comprised of higher percentages of people of color — receive hospice services (symptom management, social and spiritual support) in their last six months of life. While hospice services remain elective, current statistics show that those who do not receive end-of-life support create a significant burden on emergency rooms. Because federal law compels healthcare providers to stabilize a person when they come into an ER, people who are actively dying and do not have a primary care doctor must spend up to 14 hours waiting to have tests run or be given treatments that they already know won’t work, just to get a prescription refilled.

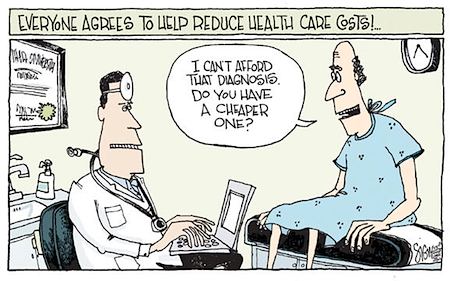

The current healthcare insurance situation in America compels the question: What can be done to better distribute resources to those people who need them most, and free up existing services to work more effectively? It’s a challenge that the country has yet to meet.

The High Cost of Dying Without Insurance

The High Cost of Dying Without Insurance

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento