We’re all well aware of the opioid crisis in the Western world. Any quick search will yield fresh news of overdoses and communities hobbled by addiction, and it’s getting worse all the time. It’s reached epidemic proportions, becoming a priority for public health officials.

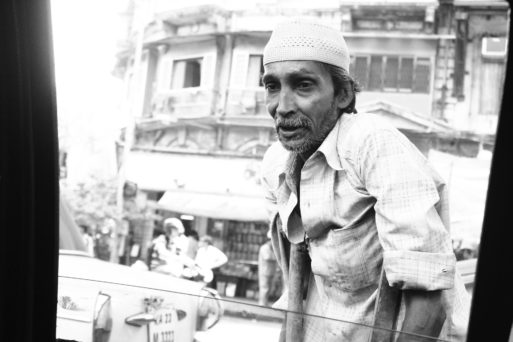

Scan those same search results, however, and you’ll find little mention of what experts have termed “the other opioid crisis” — the disproportionate lack of access to effective pain relief in low-income countries, especially in the “global south” a term used to describe low and middle income countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. The other opioid crisis doesn’t get much attention in the developed world, but it’s a real problem: According to the American Journal of Public Health, more than 61 million people worldwide experience suffering that could be alleviated with appropriate medication. And the vast majority are living in countries with little or no palliative care.

The Numbers Are Shocking

To understand what a problem this is, just look at some numbers. The 50 percent of the world’s population that lives in the poorest countries gets less than 1 percent of globally distributed morphine-equivalent opioids. And according to the International Narcotics Control Board — the U.N. agency that monitors global narcotics distribution — Europe, Canada, and the United States receive 90 percent of the world’s opiates while only accounting for 18 percent of its population. This is bad news for the dying, ill, and injured in places like India, where, despite the fact that the country is one of the world’s largest producers of legal opium, citizens receive only minuscule amounts of opioids.

It’s not a simple problem so it won’t be an easy fix. But there are a few root causes behind the crisis which experts say must be addressed if we want to find a solution. Most impactful among these are international narcotics regulation, opiophobia, and a lack of palliative care in the developing world.

Regulation Drives the Crisis

The United Nations began keeping watch on global narcotics production and distribution in 1961, and in 1968 formed the INCB. The INCB has two basic purposes, according to its mandate: (1) to ensure adequate quantities of drugs are available to every country in cooperation with governments, and (2) to monitor and interdict in the illicit drug trade in cooperation with governments.

The problem here is that the INCB has focused almost solely on illicit drugs, and done almost nothing to fulfill the first half of its mandate. The results are outdated laws requiring governments to estimate their annual opioid need and a U.N. monitoring group with a past that includes publicly shaming countries they believe used too many opioids (the INCB bases its estimates on numbers of physicians, not numbers of citizens). To avoid such shaming, poorer countries have a history of drastically underestimating their need, and tightening regulations on doctors and pharmacists. This has led to fewer available opioids and dwindling numbers of medical professionals trained to prescribe and distribute the drugs.

The One-Sided Approach of Opiophobia

The underlying reason for the mismanagement of opioids is what experts call opiophobia. The INCB blames the problem on poverty, but as the New York Times reported, it’s fear of addiction, fear of crime, and an indifferent elite that contribute most to the crisis. Again, the stigma associated with illicit drugs overshadows the needs of many.

A Lack of Palliative Care Equals Lack of Availability

Palliative care is virtually nonexistent in much of the world, and many patients who need opioids gain access to them through palliative care. Thus, if there’s no available palliative care, there are likely no opioids. The very idea of palliative care is foreign to much of the world’s population, and in many areas medical professionals are not trained to administer this type of care. This dearth has been noted by “The Lancet;” they even have a plan to fix it, which you can read about here.

The Other Opioid Crisis

The Other Opioid Crisis

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento