Pablo Picasso, a Spanish artist known widely for sparking the Cubist movement, had a long and prolific career that art historians have divided into distinct time-based categories, or “Periods.” With the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas in 1901, Picasso’s Blue Period commenced. The Blue Period lasted until 1904 and is notable for its predominantly cool tones, figurative approach that featured several portraits of Casagemas, subject matter that often included depictions of beggars, prostitutes and drunks, and themes of loneliness, mortality, human suffering and the struggle to maintain our humanity through it all. His Period filled with portraits of loss and yet helps us cultivate compassion in difficult times.

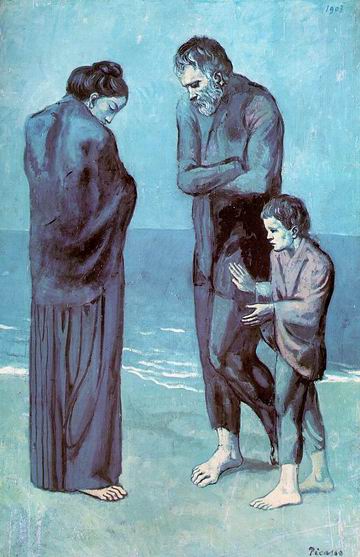

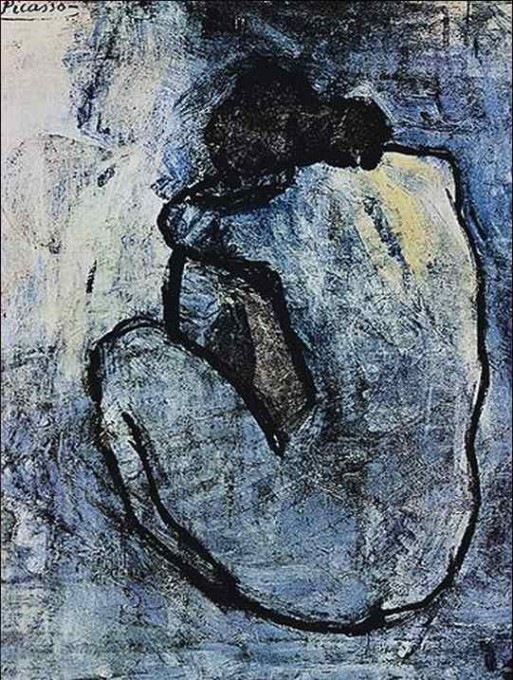

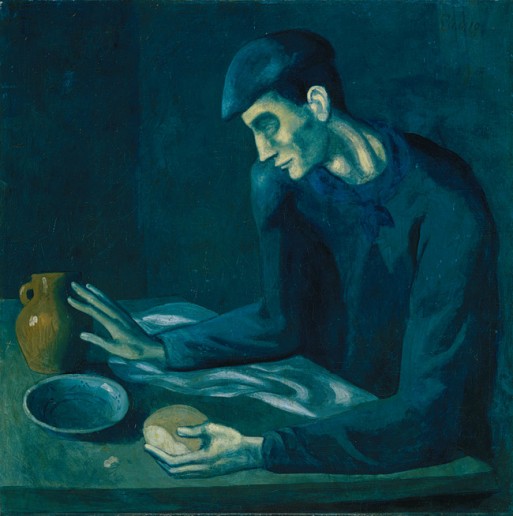

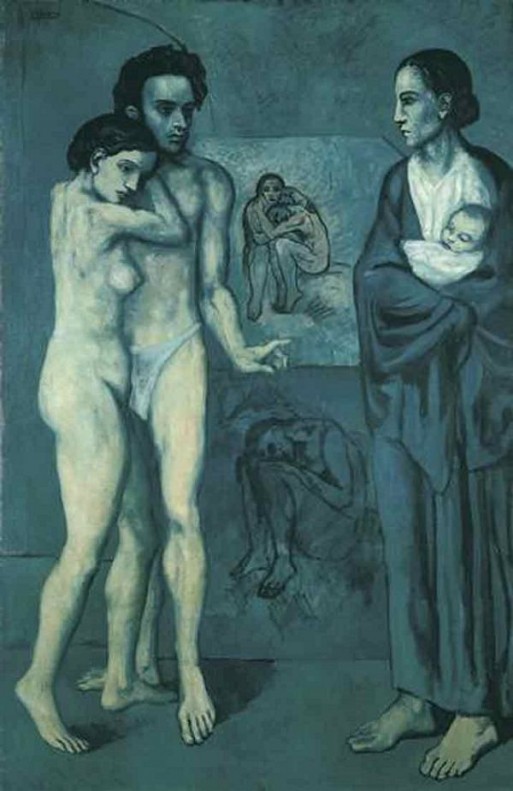

The Blue Period, stripped of the satire of Picasso’s earlier work, takes a lingering look at the ending of things. The meager, insubstantial feast of “The Blindman’s Meal” (1903), the chilly, hunched spines of the subjects of “Blue Nude” (1902) and “Des pauvres au bord de la mer” (1903) and allegorical tableaus like “La Vie” (1903) all hint at a fullness that has since waned. Generous empty space surrounding the figures suggests a vast, impersonal world in which the subjects huddle into each other, themselves, their empty cups and dirty plates, seeking refuge that isn’t there. Subjects are solitary both alone and in the company of others, suggesting a psychological isolation that is merely reflected and amplified by the physical world.

While the Blue Period seems to revel in despair, it is also an unflinching witness to the physical and spiritual poverty that Picasso’s eyes were opened to in the wake of Casagemas’ death. While Picasso’s works are often prized as decorative items, here we are offered an opportunity to confront the abyss — the depth of our own truth as individuals and as a society, revealed in instances, such as the death of a loved one, where every comforting assumption dissolves and every story we tell about who we are suddenly stops making sense.

Here we find the desolation of meaninglessness, where loss is experienced on a material, personal and universal scale. Poverty and death are conflated into a single concept, where the end of life is experienced as the end of meaning. Yet, it is also worthy to note that through grief we are able to see the suffering of others, and to linger there with a sense of kinship. (In fact, the figure of Casagemas in “La Vie” began as a self-portrait). Picasso’s emaciated, anonymous subjects holding onto their lives by a thread compel us to consider if it is possible to confront human suffering without being consumed by it, while simultaneously evoking compassion as a universal salve.

Picasso’s Blues: Portraits of Loss

Picasso’s Blues: Portraits of Loss

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento