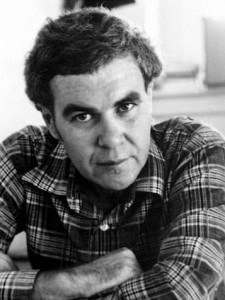

In last week’s column I wrote about Lorrie Moore, and this week, I’ve chosen another very talented short story writer: Raymond Carver. Carver is a minimalist writer, his style comparable to the economy of words Ernest Hemingway is known for. Carver was a heavy drinker, another thing he has in common with Hemingway, and many of his stories center on protagonists that are alcoholics. However, his story, “A Small, Good Thing” is a deviation from this. It is a narrative about a couple, Ann and Howard Weiss, who must face the loss of their eight-year-old son Scotty after he is hit by a car. While the majority of the tale is focused on the Weiss’s time spent waiting for Scotty to come out of his coma, the events that happen after his passing are significant and show a realistic portrayal of grief and healing.

In last week’s column I wrote about Lorrie Moore, and this week, I’ve chosen another very talented short story writer: Raymond Carver. Carver is a minimalist writer, his style comparable to the economy of words Ernest Hemingway is known for. Carver was a heavy drinker, another thing he has in common with Hemingway, and many of his stories center on protagonists that are alcoholics. However, his story, “A Small, Good Thing” is a deviation from this. It is a narrative about a couple, Ann and Howard Weiss, who must face the loss of their eight-year-old son Scotty after he is hit by a car. While the majority of the tale is focused on the Weiss’s time spent waiting for Scotty to come out of his coma, the events that happen after his passing are significant and show a realistic portrayal of grief and healing.

Initially, just after Scotty’s death, Ann and Howard are in shock, as is to be expected. When their doctor asks them if there is anything else he can do for them, Carver writes, “Ann stared at Dr. Francis as if unable to comprehend his words.” And when Dr. Francis explains that they need to perform an autopsy among other things, Howard responds, “‘I understand.’ Howard said. Then he said, ‘Oh, Jesus. No, I don’t understand, doctor. I can’t, I can’t. I just can’t.’” Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, who introduced The Five Stages of Grief, notes that “denial” and “anger” are among them, and this is what the couple is experiencing. At home, though, the pair move toward another stage, “acceptance”: “‘There, there,’ she said tenderly. ‘Howard, he’s gone. He’s gone and now we’ll have to get used to that. To being alone.’” This is an impressive step forward, seeing as Scotty has just passed. It shows the strength that people can, and indeed must have, in times of sorrow, in order to go on.

But even beyond the emotional and relatable rendering of this process, Carver includes symbolism that takes the story to an even higher level. Throughout the story, there is an ongoing presence of a seemingly insignificant character: the baker whom Ann meets when she orders a birthday cake for Scotty at the beginning of the story. This baker can be interpreted as a symbol for death. In the beginning, Ann tries to engage the baker, who is uninterested, and attempts to understand him: “She was a mother and thirty-three years old, and it seemed to her that everyone, especially someone the baker’s age-a man old enough to be her father-must have children who’d gone through this special time of cakes and birthday parties. There must be that between them, she thought. But he was abrupt with her-not rude, just abrupt. She gave up trying to make friends with him.” This mirrors mankind’s attempt to come to terms with death. We try to understand it and agree with it, but oftentimes we struggle to.

Scotty is, sadly, hit by the car on the day of his birthday, the day his cake was supposed to be picked up. When Ann fails to retrieve it because she is at the hospital, the baker continues to call the house to remind her of it. At one point, after Ann arrives home for the first time to change her clothes, she answers the phone, thinking it’s the hospital: “‘Scotty,’ the man’s voice said. ‘It’s about Scotty, yes. It has to do with Scotty, that problem. Have you forgotten about Scotty?’ the man said. Then he hung up.” This of course terrifies Ann, who immediately phones the hospital to inquire about her son and is told that nothing’s changed. At one point, after Scotty’s death, the baker calls again to say that “Scotty,” referring to the cake with his name on it, is ready, and Ann erupts angrily, “‘You evil bastard!’ she shouted into the receiver. ‘How can you do this, you evil son of a bitch?’” Ann is still unaware who it is that is calling, and as her son has just died, she is incredibly fragile. Her anger represents not only the anger and frustration of someone dealing with a loss, but also of someone who is angry at the act of death itself; here Ann screams that the baker is “evil,” which reflects her resentment at death taking her son away from her.

Scotty is, sadly, hit by the car on the day of his birthday, the day his cake was supposed to be picked up. When Ann fails to retrieve it because she is at the hospital, the baker continues to call the house to remind her of it. At one point, after Ann arrives home for the first time to change her clothes, she answers the phone, thinking it’s the hospital: “‘Scotty,’ the man’s voice said. ‘It’s about Scotty, yes. It has to do with Scotty, that problem. Have you forgotten about Scotty?’ the man said. Then he hung up.” This of course terrifies Ann, who immediately phones the hospital to inquire about her son and is told that nothing’s changed. At one point, after Scotty’s death, the baker calls again to say that “Scotty,” referring to the cake with his name on it, is ready, and Ann erupts angrily, “‘You evil bastard!’ she shouted into the receiver. ‘How can you do this, you evil son of a bitch?’” Ann is still unaware who it is that is calling, and as her son has just died, she is incredibly fragile. Her anger represents not only the anger and frustration of someone dealing with a loss, but also of someone who is angry at the act of death itself; here Ann screams that the baker is “evil,” which reflects her resentment at death taking her son away from her.

However, after this exchange, Ann realizes that it is the baker who has been calling, and she decides that she must go and speak with him. Though it is after midnight, the baker reluctantly lets the couple in. After Ann explains everything, the baker feels awful: “‘But I’m deeply sorry. I’m sorry for your son, and sorry for my part in this…’” The baker is referring to his numerous phone calls, but as the representation of death, he is apologizing for having to take Scotty. As Carver puts it, “He had a necessary trade.”

The couple forgives the baker, and they end up staying and eating the food he offers them: “They listened to him. They ate what they could. They swallowed the dark bread. It was like daylight under the fluorescent trays of light. They talked on into the early morning, the high, pale cast of light in the windows, and they did not think of leaving.” Eventually, Ann and Howard are able to move more concretely toward the “acceptance” stage of grief, and they gain a better understanding of death, having given the baker a chance.

“A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

“A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

“Other Side” Documents Woman’s Fight To Die As She Wishes

“Other Side” Documents Woman’s Fight To Die As She Wishes

The Other Death in the Family

The Other Death in the Family