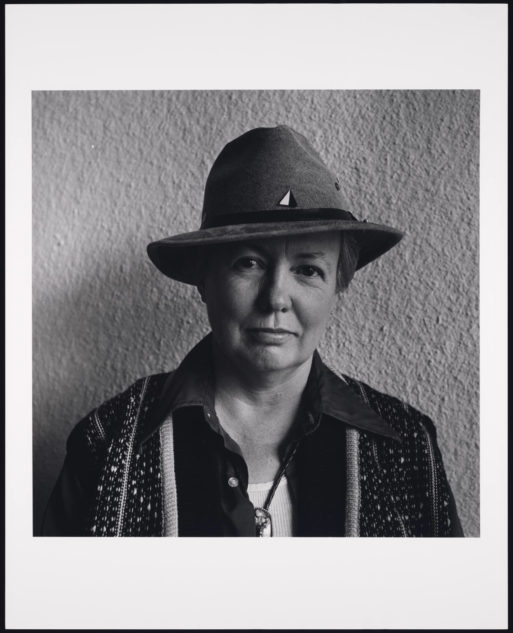

Credit: maggiesmetawatershed.blogspot.com

“we are the fat of the land, and

we all have our lists of casualties”

Judy Grahn’s ambitious, arresting work, “A Woman Is Talking to Death” is her most celebrated poem, a piece about meaning and futility, callousness and tenderness, queer love and, of course, death. The poem is a factual account of a fatal motorcycle accident on the Bay Bridge — the bridge that connects San Francisco to Oakland — that expands into a meditation on the differences between love and death. Grahn said of the poem that it was “a redefinition for myself of the subject of love.”

It’s also one of the most beautiful pieces about death I’ve ever read. It’s an impossible poem to pigeonhole. It’s very lengthy, first of all, and covers a lot of ground. It’s a story about a traffic accident; an incantation (many repeating lines throughout); a commentary on the challenges (and loneliness) of being an out lesbian in the seventies; and a defiant clap back to death’s thieving ways — death, who “wastes our time with drunkenness and depression/death, who keeps us from our lovers.”

Grahn weaves themes and metaphors and historical references and present day events lyrically and poignantly. Policemen as agents of death; racism in the criminal justice system; the personal destruction wrought by a homophobic society; the European witch trials all appear and connect with certain repetitive lines that structure the skeleton of the poem. Grahn believes that poets build community by “making cross connections and healing the torn places in the social fabric of myth we have all inherited, but that the outcast especially inherits.”

The narrator of the “A Woman Is Talking to Death” addresses death directly in some of the poem’s most powerful lines:

“I want nothing left of me for you, ho death

except some fertilizer

for the next batch of us

who do not hold hands with you

who do not embrace you

who try not to work for you

or believe you, ho ignorant

death, how do you know

we happened to you?”

Credit: poetryfoundation.org

The narrator, powerless in so many of the situations she’s detailed throughout the poem, stands in her power as she directly challenges death. She finishes the poem laughing at death, determined not to bequeath her life to death, but rather to her lovers. And at that point she has expanded the word “lovers” to include her lesbian lover Wendy; the lesbians in the military who went down with her when she was kicked out; a classmate of hers who became pregnant while they were still in junior high; and a host of others.

“wherever our meat hangs on our own bones

for our own use

your pot is so empty

death, ho death

you shall be poor”

“A Woman Is Talking to Death” by Judy Grahn

“A Woman Is Talking to Death” by Judy Grahn

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?